One Country, Many Voices

One Country, Many Voices

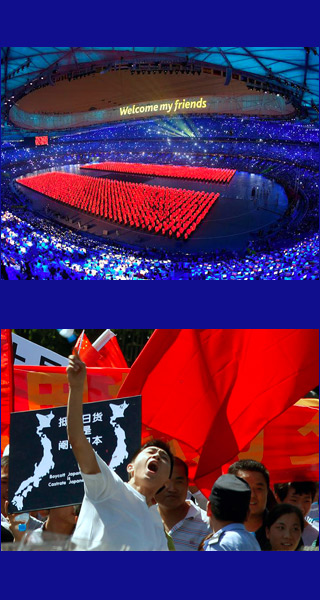

IRVINE: Four years ago, when the Beijing Olympic slogan was “One World, One Dream,” global audiences were wowed by a Chinese spectacle that began with a quote from Confucius describing the pleasure of welcoming friends from afar. Now, the sounds coming from China and grabbing our attention are not spirited drumming but angry chanting about settling scores.

It’s worth comparing the recent street actions in China, triggered by an ongoing dispute over control of specks of land known as the Diaoyu Islands in Chinese, the Senkaku Islands in Japanese, with the mesmerizing gala of the Beijing Games. The two spectacles offer a striking study in contrasts – and intriguing parallels.

Let’s start with contrasts.

The 2008 spectacle, choreographed by filmmaker Zhang Yimou, was held in one locale and, though filled with historical allusions, included no nods to Japanese invasions or direct references to Chairman Mao. Today’s demonstrators, marching through streets across China, carry portraits of Mao and refer continually to past atrocities committed by Japanese soldiers.

The Communist Party, keen to remind the populace that it once battled imperialism and now protects China from foreign bullying, tries to guide the anti-Japanese protests. In some cases, especially in the capital, according to journalists such as NPR's Louisa Lim, the government has been doing more than that: directly stage-managing demonstrations and ordering employees, including plainclothes police, to join the parades.

Not all protests are choreographed. In some cities, demonstrators have departed from official scripts, slipping in complaints about corruption, calls for reform or laments about China lacking a strongman leader like Mao.

The government finds the protests useful, but also worries they’ll spin out of control.

International response to the 2008 and 2012 spectacles diverged. Foreign commentators criticized elements of fakery in the former, such as the beautiful voice of one girl presented as belonging to another, and a North Korea–like kind of lockstep conformity. On the whole, though, critics found more to applaud than complain about, expressing appreciation of a China presented as respecting tradition, but eager to move forward and make friends. This year’s street displays, by contrast, have been roundly condemned.

The comparisons may be more intriguing.

One parallel concerns the desire of China’s leaders to convince domestic audiences that conflicts in society and among party factions are part of the past. The Opening Ceremonies emphasized the theme of harmony in a country where everyone works together for common goals. The current protests likewise play up an us-versus-them stance toward Japan, helping divert attention from the Bo Xilai scandal and its revelations about the dark side of party factionalism.

Another connection is the tendency of many foreign observers to underestimate the diversity of China’s population. When entrancing or appalling spectacles capture global attention, commentators too often fall into the trap of forgetting how selective a window these events provide on the thinking of a large, heterogeneous group of individuals. The 2008 games inspired a host of comments that overstated China’s degree of uniformity. The anti-Japanese protests are doing the same.

Zhang’s 2008 production inspired many generalizations about “the Chinese,” including claims that all share an intense admiration for Confucius and respect for their country’s ancient history. This line of thinking also informed high profile books published in the wake of the Games, such as When China Rules the World and Henry Kissinger’s On China. The sense conveyed was that, leaving aside restive ethnic groups such as Tibetans and Uighurs and some daring dissidents, the Chinese people are on the same page when it comes to beliefs and the past. This isn't so.

For instance, while many Chinese admire Confucius, many prefer Taoist sages, frequent Buddhist temples, or have always been or recently become Christians. Yes, some Chinese have a reverential attitude toward the distant past, but many couldn’t care less about events that happened before they were born, let alone millennia ago.

The Chinese were not even on the same page about the Opening Ceremonies. Many liked it but, as Geremie Barmé noted at the time in China Beat, some intellectuals labeled its treatment of China’s past as disappointing: One lamented looking forward to a “banquet” of delectable historical morsels, only to get a “hot-pot” of mishmash. And writing in The Diplomat, Susan Brownell stresses that in China, as in the West, the show’s similarity to a rigid North Korean state-run spectacle became an issue.

Generalizations about “the Chinese people” tend to get more play than they deserve. Sparking concern just as the recent anti-Japanese outburst began was a passing comment in an otherwise admirable New York Times op-ed by political scientist Peter Gries, which referred to “most Chinese” feeling that “the Japanese are ‘devils.’” Yes, the character for “demon” is embedded in a term for the Japanese sometimes used in China, and patriotic education drives do go to great lengths to keep alive the memory of the Rape of Nanjing and other historic acts of Japanese aggression. It’s a big leap, though, to conclude that most Chinese view all Japanese as less than human. Many Chinese are capable of being appalled by what Japan’s soldiers once did in China without assuming that all Japanese are devilish.

The recent protests have involved just a fraction of the population of any Chinese city, and people joined marches for varied reasons – visceral hatred, just doing their job, specific anger over Tokyo’s actions vis-à-vis the disputed islands, or eagerness to participate in a protest of any kind.

Some Chinese are critical of the anti-Japanese protests. Novelist, racecar driver and blogger Han Han clearly is. He published a powerful essay in 2010 about the hollowness of that year’s partially orchestrated anti-Japanese protests and has just written a sequel mocking the notion that smashing Toyotas proves one’s patriotism. Each of his posts is read by roughly a million people, and he’s not the only popular writer satirizing the protests.

A recent Atlantic.com article by Helen Gao describes an illuminating online poll. Chinese readers were asked this summer what citizenship they’d prefer for a child born on the disputed islands. The comment thread for the poll suggests that respondents weighed patriotism against a desire for their offspring to enjoy free expression, clean air and safe food. While many answered that they’d like this imaginary child to be a PRC citizen, more preferred that their offspring grow up Taiwanese or Japanese.

We can learn about China from spectacles. If staged or simply permitted by the government, they offer insights into leaders’ thinking. If participants choose to join, we get clues about beliefs and passions. Equally revealing, though, are the debates taking place in dorm rooms and teahouses, on street corners and online, which are wide-ranging and undermine the notion, promulgated by the Communist Party and some foreign commentators, that nearly everyone in China shares a unified worldview.

Jeff Wasserstrom is the author of China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know, co-editor of Chinese Characters: Profiles of Fast-Changing Lives in a Fast-Changing Land, Asia editor, Los Angeles Review of Books; Chancellor’s Professor and Chair, history Department, University of California at Irvine; and editor, Journal of Asian Studies. He can be reached at @jwassers