The Opportunity of the Cartoon Crisis

The Opportunity of the Cartoon Crisis

SINGAPORE: The Chinese word for “crisis” is brilliant: It combines two characters: danger and opportunity. The crisis over the Danish cartoons on Islam presents many dangers, but also offers some opportunities.

The first opportunity the crisis provides is to educate us on how much the world has changed. Before this crisis, the 5.4 million Danes could retain the illusion that they sailed on a different boat from the world’s 1.2 billion Muslims. Now they, like most Europeans, are aware that those Muslims share the same boat. None of us would board a boat and deliberately rile a large group of fellow passengers. If one group rocks the boat, we would all sink together. The Danish cartoon crisis has demonstrated that the 5.4 million Danes, and 400 million fellow EU citizens, share a common political and emotional space with 1.2 billion Muslims. These Muslims are experiencing a deep existential angst, an angst aggravated by the Danish cartoons. Their anger can rock our boat. The widespread riots and loss of life that followed should now spur us to understand the deep roots of this anger.

The Danes are familiar with the proverbial expression of the straw that broke the camel’s back. The cartoons, perhaps only a straw, reinforce the deep sense of injustice that many Muslims feel. Muslims are convinced that the world, especially the West, shows no moral concern over their plight. The loss of innocent Muslim lives, whether in Iraq and Palestine, Afghanistan or Pakistan, does not stir the world. Nor has the West shown any real interest in supporting the development of Muslim societies. In short, the cartoons hurt the Muslims badly because they add real insult to real injuries.

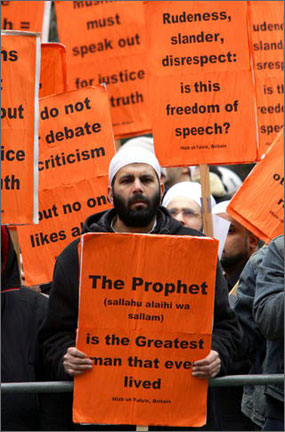

The second opportunity this crisis provides is for the 1.2 billion Muslims to engage in some deep reflection. If they were strong and powerful, no small European country could afford to anger and alienate them. The ability of a Danish newspaper to publish the cartoons and the subsequent decision of several European papers to republish them demonstrated the weakness of the Muslim world. The Europeans knew that Muslims could not retaliate and hurt Europe. Hence, Muslim sensitivities could be ignored. Mass demonstrations, including assaults on the Danish embassies in Damascus and Beirut, are not an expression of strength. As Tariq Ramadan said, “The Muslim reaction is far too excessive and not the way forward.” The Muslim world has neither hard power nor soft power and lags behind Europe in social and educational indices. As such, the Muslim world needs to understand why it has become so weak relative to Europe.

A thousand years ago, when the Muslim caliphates were shining brightly, while preserving the rich fruits of Greek and Roman civilizations, Europe was emerging from the Dark Ages. In the contest between civilizations, the Muslims had clearly surpassed the Christians by the year 1000. Today, despite its many problems, Europe is far ahead. Why do so few Muslims ask the obvious question: How did the Muslim world, like much of Asia, lose a thousand years? China too lost many centuries in catching up with the West. So did India. But both civilizations are finally waking up, absorbing the best practices of the West, including a careful delineation of the roles of religion and state in the development of modern societies. If the Muslim world cannot emulate the West, can it emulate China and India? The Prophet Muhammad once said: “Seek knowledge, even into China. That is the duty for every Muslim.” If Muslims heeded such advice, Europe may not have drawn offensive cartoons.

The third opportunity from the crisis is for the world to reflect on the vices and virtues of freedom of expression. The Danish prime minister’s defense is that his government could not stop the publication of the cartoons because freedom of expression is an absolute value. Technically, he is right. No Danish law would allow him to stop the cartoons. But societies do have sensitivities. The Danish insensitivity to the Muslim world has clearly come through. As Jonathan Eyal noted in the Singapore Straits Times, “No self-respecting European newspaper would dare to publish a cartoon making fun of the Holocaust, the systematic murder of Jews during World War II.” Every society has its taboos. Today every society has to respect its own taboos and those of its neighbors. There is one simple reason why a few Danish cartoons could rock the world. The world is no longer a world. We live in the same neighborhood. Every human is our neighbor. The Muslims are our neighbors, too. We must respect their sentiments.

And yet it would be a great loss for mankind if the virtue of freedom of expression were sacrificed or diminished as a result of this cartoon crisis. Even the Muslim world would suffer. The sad reason for the struggle of many Muslim societies is that they have some dysfunctional aspects. Some of their elites feather their own nests, not that of their populations. The lack of a free press in many parts of the Muslim world prevents critics from exposing the inequities. Hence, the Muslim world should welcome rather than reject a free press. Look, for example, at the brave work done by Tempo, Indonesia’s leading weekly newsmagazine. Only it has the courage to point out both the weaknesses of the Indonesian government and the Muslim extremists who try to stifle debate in Indonesia. The Muslim world needs more Tempos, not fewer.

But the virtues of freedom of expression would be better appreciated in the rest of the world if the Western media, which dominate the world’s airwaves, encouraged a two-way street of ideas instead of the current one-way street. The open bewilderment of the Danes and Europeans at the global Muslim reaction to the Danish cartoons only reflects the widespread ignorance of the existential conditions of the Muslim world. It is no great secret that the Muslim world feels trampled upon by the West. They resent the double standards of the Western media on human rights, protesting strongly when non-Muslims are killed, as in East Timor, and protesting mildly when Muslims are killed, as in Palestine and Iraq. The Western media has convinced Western publics that they are paragons of virtue on human rights issues. But the Muslims, together with most of the five billion people who live outside the West, are acutely aware of the double standards.

The Danish cartoon crisis therefore provides the Western media an opportunity for self-reflection: How could they have failed to explain the viewpoint of five-sixths of humanity to their own populations? How can a free press be so irresponsible?

In short, despite the strongly held beliefs by both sides, there are no saints and sinners in this crisis. Both sides should engage in deep reflection on what they have done to allow the emergence of this crisis. When the dust has settled and the demonstrators have gone home, we should begin to work out the long-term future of mankind. Is it tenable for us to live in the same neighborhood and ignore the sentiments and wisdom of large segments of humanity? Is it wise for us to temper the open debate that the virtues of freedom of expression allow? Is it reasonable to allow the continuation of a one-way street in the passage of ideas from West to East? These are hard questions. The Danish cartoon crisis has provided us an opportunity to address them head on.

Kishore Mahbubani is the dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, NUS, and the author of “Can Asians Think?” and “Beyond the Age of Innocence: Rebuilding Trust between America and the World.”