Pakistan: Nuclear Power with Feet of Clay?

Pakistan: Nuclear Power with Feet of Clay?

BOSTON: Backed by nuclear weapons and the seventh largest standing army in the world, Pakistan has the ability to project its power externally, but lacks the strength of an effective state at home.

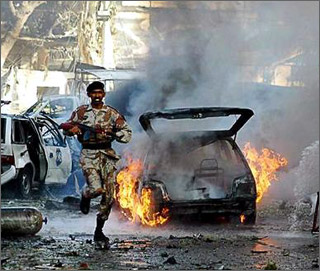

The recently released video of the Taliban using a young boy, believed to be 12 years old, to behead a man amid cries of “Allahu Akbar” is only one of several troubling images emanating from Pakistan. Attacks by armed supporters of a pro-government militia on opposition activists in the port city of Karachi and frequent terrorist bombings revive fears about Pakistan’s future.

The country faces increasing demands from religious extremists, and doubts are growing among Pakistan’s Western allies about the military regime’s ability to handle these pressures.

Paradoxically, Pakistan has turned out to be a hot destination for investors from the Gulf, encouraged by business friendly government policies and annual GDP growth rates of 7 percent over the last four years. Pakistan’s privatization program is considered a regional success. Government economists cite increasing mobile phone use and expanding sales of motorcycles and cars as signs of progress.

Pakistan’s elite now drive around in Porsches, more of which have sold in the city of Lahore alone than the car’s manufacturer had envisaged for the entire country. The pace of construction for new country clubs, golf clubs and luxury hotels also reflects growing prosperity of a select few.

That this strife-ridden country with a booming economy seems precariously balanced between chaos and growth should not, however, be a source of comfort. Given widespread anti-Americanism and signs of rising support for Islamist sentiment in the military, Washington cannot count on the military to keep the balance. If Pakistan falls from its shaky perch, the consequences for the region and the US could be dire.

Pakistan is viewed as a critical Western ally in the global war against terrorism. Relations with arch-rival India have improved markedly since four years ago, when the armies of the two nuclear-armed neighbors stood eyeball-to-eyeball. Pakistan reveals multiple realities, and the temptation to let optimism prevail is great. But, in essence,

Pakistan has become a dysfunctional state, a tinderbox that may not light up for years, but could also go up in flames in an instant.

At least 1,471 people were reported killed in terrorist incidents in Pakistan during 2006, up from 648 terrorism-related fatalities during the preceding year. Of these, 608 were civilians, 325 security personnel and 538 accused terrorists. The rising fatalities of security forces indicate the growing strength of armed non-state actors, especially extremists.

An army, largely recruited from one of the country’s four ethnically diverse provinces, has traditionally maintained order in Pakistan. The military’s ability to keep a lid on dissent has diminished with the emergence of well-armed militias, both Islamist and secular, in various parts of Pakistan.

Vast parts of Balochistan, the sparsely populated southwestern province bordering Afghanistan and Iran, are virtually ungoverned. A secular, tribal insurgency in Balochistan has been overshadowed by the resurgence of the Taliban in the province’s north.

The brutal beheading involving the 12-year old took place in Balochistan and involved the ethnic Pashtun Taliban punishing an ethnic Baloch for allegedly spying on behalf of the Americans and their allies. The Taliban also control the generally uncontrolled tribal areas in the Northwest Frontier province (NWFP) and gradually expand their influence into the adjoining non-tribal settled districts.

Balochistan accounts for 42 percent of Pakistan’s territory, and the Pashtun tribal areas represent 3 percent of the land area. Even if one ignores the rising violence and lawlessness in urban Pakistan, almost half the country now constitutes an anarchistic or inadequately governed space.

In addition to problems in Balochistan and NWFP, at least 200 people have died in sectarian violence between Shia and Sunni militant groups across the country during the last year.

General Pervez Musharraf, who came to power in a coup d’état in October 1999 and remains a clear favorite of the Bush administration, has made no effort to encourage democratic institutions. Musharraf’s decision to marginalize Pakistan’s secular political parties to avoid sharing power has strengthened radical Islamist groups.

Lately, Pakistani civil society has stirred in reaction to the domination of the country’s life by the military and assorted Islamist militants. For the past two months, lawyers in suits join activists from opposition political parties in demonstrations protesting the removal from office of the country’s chief justice.

Amid widespread disorder and the emboldening of insurgents and terrorist groups, Pakistan successfully tested the latest version of its long-range nuclear-capable missile, in February. The Hatf VI (Shaheen II) ballistic missile, launched from an undisclosed location, is said to have a range of 2,000 kilometers and has the capability to hit major cities in India, according to Pakistan’s military.

In the process of building extensive military capabilities, Pakistan’s successive rulers have stood by as essential internal attributes of statehood degrade. A major attribute of a state is its ability to maintain monopoly, or at least the preponderance, of public coercion.

The proliferation of insurgents, militias and Mafiosi reflect the state’s weakness in this key area. There are too many non-state actors in Pakistan –ranging from religious vigilantes to criminals – who possess coercive power in varying degrees. In some instances the threat of non-state coercion in the form of suicide bombings weakens the state machinery’s ability to confront challenges to its authority.

Since its emergence from the partition of British India in 1947, Pakistan has defined itself as an Islamic ideological state. The country’s praetorian military has held the reins of power for most of the country’s existence and seen itself as the final arbiter of Pakistan’s national direction.

The emphasis on ideology has empowered Pakistan’s Islamist minority. The overwhelming influence of the army has accentuated militarism at the expense of civilian institutions. Many Pakistanis view the US as the army’s principal benefactor and by extension partly responsible for weakening civil institutions. The three periods of significant flow of US aid to Pakistan have all coincided with military rule in Pakistan.

The disproportionate focus of the Pakistani state on ideology, military capability and external alliances since Pakistan’s independence in 1947 has weakened the nation internally. Pakistan spends a greater proportion of its GDP on defense and still cannot match the conventional forces of India, which outspends Pakistan 3 to 1 while allocating a smaller percentage of its burgeoning GDP to military spending. The country’s institutions – ranging from schools and universities to political parties and the judiciary – are in a state of general decline.

Much of the analysis on Pakistan in the West since 9/11 has focused on Musharraf’s ability to remain in power and keep up the juggling act between alliance with the US and controlling various domestic constituencies, including the Pakistani military and Islamist militants. Pakistan’s problems, however, run deeper. It is time the world set aside its immediate preoccupation with Musharraf’s future to examine the fundamental conditions of the Pakistani state.

Husain Haqqani is director of Boston University’s Center for International Relations and co-chair of the Hudson Institute’s Project on Islam and Democracy. He is the author of the Carnegie Endowment book “Pakistan Between Mosque and Military.”