The Plot Thickens: Testing European Tolerance

The Plot Thickens: Testing European Tolerance

BRUSSELS: The killing of controversial Dutch film-maker Theo van Gogh by a suspected Islamic extremist and the subsequent spate of retaliatory attacks on Muslim targets are a damaging blow to relations between European Union's 15 million Muslims and their host communities. Dutch violence has also spotlighted the need to speed up the integration of Muslim immigrants in the EU and opened a debate on the place of Islam in an increasingly secular Europe.

Van Gogh, who had just made a controversial film condemning Islam's treatment of women, was shot and stabbed in Amsterdam as he cycled to work. Van Gogh's killer has been identified as 26-year-old Mohammed Bouyeri, a Dutch-Moroccan. Another five alleged Islamic radicals face charges of forming a terrorist conspiracy to murder van Gogh.

The outpouring of anti-Islamic and anti-immigrant sentiments in the Netherlands after van Gogh's murder reflects a harsh new reality in a country once known for its tolerance. Van Gogh's brutal slaying has been condemned by Muslim groups in the Netherlands, anxious to distance themselves from the crime. Nonetheless, a recent poll conducted by Dutch TV showed that 47 percent of all people in the Netherlands now feel less tolerant of Muslims. Since the van Gogh murder, mosques have been set on fire and bombs exploded in Islamic schools across the Netherlands.

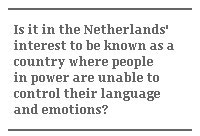

Many Dutch politicians, including members of the ruling center-right coalition (Christian Democrats and Liberals) have lashed out against the country's one million Muslims. Deputy Prime Minister Gerrit Zalm has declared a "war" on Islamic extremists. Rightwing Dutch MP Geert Wilders wants all mosques attended by radicals to be closed. The EU's outgoing internal market chief Frits Bolkestein, also a Liberal from the Netherlands, has latched on to the fact that van Gogh's killer is of Moroccan origin (but also Dutch) to ask the Moroccan king to stop "his" citizens from engaging in terrorist acts. It was not in Rabat's interest, said Bolkestein, to be seen as an "exporter of murderers."

But is it in the Netherlands' interest to be known as a country where people in power, when faced with a very public national trauma, are unable or unwilling to control their language and emotions? Responsible politicians in a mature European democracy must show grace under fire, says Claude Moraes, a Socialist member of the European Parliament who heads the assembly's recently launched group on anti-racism and diversity. "Politicians need to be more thoughtful," says Moraes. There is also concern that far right parties in the Netherlands are exploiting van Gogh's murder to foment further conflict with the Muslims in the country.

Racial and religious violence in the Netherlands is prompting serious worry in the rest of Europe: Political leaders fear that the bloody events may signal the beginning of a new, more violent phase in already-tense relations with their own Muslim minorities.

Van Gogh's killing and the subsequent anti-Muslim hostility is potent proof that despite their public wishes to avoid a "clash of civilizations" and strong efforts to build bridges with Arab and other Islamic countries, European governments have done little to engage in a real dialogue with their own Muslim citizens. Islamophobic sentiments are certainly on the rise throughout Europe, according to reports published by the Vienna-based Center for Monitoring Racism and Xenophobia. The September 11 attacks on US cities and the Madrid railway bombings have made ordinary Europeans increasingly wary of their Muslim co-citizens.

While tough measures are clearly needed to clamp down on Islamic extremist groups, terrorist organizations, and networks linked to Al Qaeda, crackdowns are further inflaming inter-community and inter-religious tensions, making the integration of Muslims even more difficult.

One result of this widening divide has been the radicalization of young Muslims. While young women are wearing headscarves to underline their Islamic identity, young Muslim men are being tempted by the "seductive discourse" of radicals, says Marco Martiniello of the Center for Ethnic and Migration Studies at the University of Liege. The fact that even multicultural societies such as the one in the Netherlands have failed to eliminate discrimination, with Muslims facing racism at school and unable to secure good jobs or find proper housing, is a further strain on inter-community relations.

"Discrimination and exclusion" of Europe's Muslim minorities is a fact of life, Dutch Immigration Minister Rita Verdonk admitted recently. "Young people feel rejected by society," Verdonk recognised, adding that integration of Muslims was difficult because they "don't speak the language, lack appropriate training or education and have little knowledge of society."

Societies such as the Netherlands, which appear to embrace diversity, often create false "aspirations of equality" among immigrants which can then turn to feelings of deep frustration when discrimination persists, says Martiniello. As a result, even "well-integrated young Muslims feel distanced from the host society, which can breed alienation and tensions," admits an EU official.

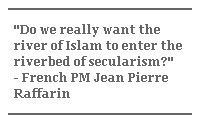

The increasingly emotional debate about Turkey's planned membership in the European Union has also brought long-held prejudices, based on Europe's historical clashes with Islam, back to the fore. Some of the political discourse on Ankara's bid to join the EU is openly Islamophobic, with politicians, especially in France and Germany, warning against the dilution of Europe's Christian values. French Prime Minister Jean Pierre Raffarin cautioned recently against Turkish entry, saying it was dangerous to allow "the river of Islam to enter the river bed of European secularism."

There is a growing rift between a secular Europe, which espouses progressive values on issues like abortion and gay marriages, and a religious minority that holds a more conservative view of the world. While Muslim unease with Europe's secularism is often in the news, Christians are also anxious about the erosion of their values, says Meindert Fennema of the Institute of Migration and Ethnic Studies in Amsterdam.

Many politicians in the Netherlands and elsewhere are insisting that immigrants must "assimilate" into European societies, completely giving up their religious and cultural identity, says Martiniello. This has taken the focus away from the concept of "integration," which allows for diversity.

EU governments have few options, however. European leaders at a summit in early November admitted the need for legal migrants to compensate for domestic labor shortages and an aging population. An EU report published last year said that the working age population in the 25-nation bloc was set to fall from 303 million to 297 million by 2020, and to 280 million by 2030. Immigrants are deemed essential to develop Europe's information technology sector and to bolster overall economic development – advancements necessary for the EU to meet its ambitious goal of becoming the world's most competitive economy by 2010. "Immigration can help in filling current and future needs of EU labour markets," the report said.

The dilemma for EU leaders, however, is that while the economy needs immigrants, European society is not in welcoming mode. Before they can recruit workers abroad, governments will have to put money, time, and energy into making sure that immigrants, especially Muslims, are able to become part of the economic, political, and social mainstream. Allowing in more immigrants without ensuring the integration of those who are already in Europe will mean more clashes like those in Netherlands.

Shada Islam is a Brussels-based journalist specializing in EU policy and Europe’s relations with Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.