The Politics of Globalization

The Politics of Globalization

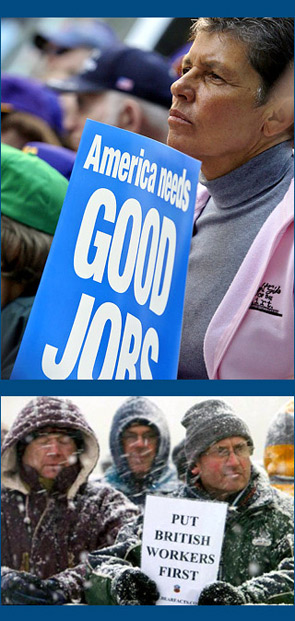

LONDON: As globalization transforms the world, societies and nations are becoming increasingly uneasy.

Yet no one in China, Vietnam, India, or Botswana – let alone the educated young adults in Europe or the US – is in a hurry to reverse integration into the global economy.

Globalization drives trade and innovation, pushing down consumer prices, be it the basics of food and clothing or the luxuries of cars and computers. But the voracious appetite for energy and other natural resources leads to competition and unease, a global race that threatens stability.

Modern economic life seems to me to be characterized pretty simply: new opportunity for many, new uncertainty for most. And two views of globalization are emerging: first, the “Davos view,” seen from 10,000 feet of new opportunity and aggregate growth and, second, the view from the factory gate where globalization is seen as a zero-sum game in which jobs and opportunities in the fast developing world are created at the expense of employment and the standard of living.

Anxiety also emerges among countries with different economic rules. Although the narrative of free trade and liberal economics driving innovation persists, there is a more ambiguous reality, in which some states play by the liberal rules of free economic competition when it suits them, and the rest of the time distort the costs of capital, protect and subsidize industry and operate opaque systems of regulation. The tensions among the fastest growing emerging economies are as great, if not more so, than between developing and developed countries.

As global competition grows more intense, each country grasps any tool to gain advantage in others’ markets while protecting their own: Russia has set up a sovereign wealth fund so that it can subsidize inward private equity investment. China has added rules governing “national security,” adding to investment uncertainty as it seeks increased international access for outgoing investment. Australia has revised its takeover rules to prevent China buying up wholesale its natural resources.

That the economy has moved beyond our control creates anxiety – globalization is something done to us rather than for us. Far from celebrating globalization, many plead for protection. To this, the financial crisis adds complexity. Unregulated finance capital grew ahead of our ability to manage it, ultimately causing the crash, and for many this exemplified the unaccountable, volatile power of global markets. Jobs and pensions became collateral damage.

This is the defining problem for 21st-century politics in the developed world.

Undermining globalization’s huge benefits are distorting interventions of state capitalism from one direction and anxious politics of an increasingly defensive developed world from the other. The poorest countries are most likely to be uncomfortably squeezed by any clash of interests amongst the more developed countries.

For these reasons, there’s urgent need to improve the politics of globalization.

Institutions are in place to shape globalization along with an array of public policy tools that aim for greater security. Yet the potential of the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, the G20, the World Bank and especially the World Trade Organization is underestimated.

The WTO is the only global organization operating in the economic sphere which sets multilateral binding rules with a disputes mechanism for settling conflicts. The WTO must help raise the bar of openness in the global economy to generate growth and reduce poverty. States have surrendered more sovereignty to the WTO and the GATT over the last 50 years than to any other institution or system, possibly with the exception of the Eurozone. The calculation is that a common set of rules for trade, binding on all, is better for all.

Governance of the trading system can go further. While bilateral free-trade agreements have opened trade in the global economy over the last two decades, they cannot do what multilateral agreements can achieve. The WTO should be given new powers to police Free Trade Agreements for transparent and fair trade, and we must exact a minimum ethical price for openness with no back-sliding on previously agreed rights. The EU and the US in particular must be prepared to lead by example in the removal of tariff barriers and subsidies.

To achieve agreement on Doha we must have the courage of our convictions that trade and openness are essential for growth, and the determination to build the domestic policy frameworks that will ensure that everyone, including the most vulnerable, can benefit.

The West won’t win by engaging in a race to the bottom – and must compete in the global economy through specialization and by adding value to everything we do. Developed nations can maintain their share of world markets by making more sophisticated products and incorporating technological prowess at every stage. They must compete on quality rather than price. Collective action, led by government, can prepare these economies for global competition.

In fact, I have trouble conceiving of an intelligent response to globalization that does not involve greater collective action.

One of the biggest misconceptions about globalization is that it forces us to make a trade-off between collective action and social protection on one hand and competitiveness on the other. This is not the case. Globalization does not make strong social protections untenable. If anything, it makes them more essential.

Put globalization in context: It’s a powerful, ubiquitous trend, but hardly the cause of everything bad or good in our economies. Research by the Carnegie Institute that has examined US wage stagnation since the 1970s stresses the impacts of mechanization in many workplaces, along with their de-unionisation, and significant upward redistribution of income through the tax system as much as globalization.

In other words political choices are involved.

The flexicurity models of Scandinavia – enabling workers to participate in the labor market and move confidently between jobs – have kept unemployment levels low during this recession. Taxpayer funds – spent to protect citizens against life-destroying unemployment or ill health – actually hedges against higher costs of long-term unemployment and economic inactivity.

Social programs equip people to adapt and thrive. A society that ignores preventative care, leaving individuals to cover the costs of health care or unemployment, is an insecure society. Insecure societies are one political step away from protectionism and isolationism.

Of course there are limits to any policy of redistribution. It’s counterproductive to raise the share of pooled resources in a society to the point where individuals lose incentives to work or innovate. Education, the public science base, the shared infrastructure, these are the prerequisites for effective competition. Free markets do not provide these for societies alone.

Yet throughout the West, governments are retrenching under the pressure of sovereign debt and deficit reduction. In reshaping the roles of the state, leaders must understand the limits of what governments alone can do. Markets and government must come together, asking how to balance free market theory with social democratic intervention? How does social confidence underwrite economic success?

The challenge is one of balance.

Government cannot become monolithic. The desire to see business behave ethically cannot become suspicion of business in principle. Government that develops the capacities of citizens to do more than sink or swim need not stifle competition, micro-manage companies or develop national champions. Necessary debate about the politics of redistribution need not discourage individual contributions or remove incentives for economic activity.

The case for globalization needs to be re-made for a new economic and political era.

Comments

good