Power Shift in China – Part II

Power Shift in China – Part II

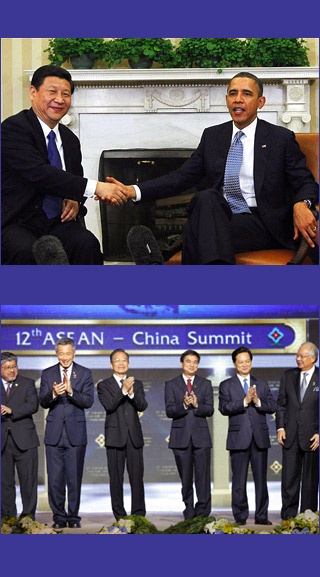

NEW HAVEN: If President Obama is reelected this fall, his relationship with Xi Jinping will be a key factor in how relations between China and the United States develop. Unless China and the United States can find ways to block the current drift toward strategic rivalry, tensions will rise. This will make it more difficult to preserve the climate of peace and prosperity that has made East Asia such a dramatic success story.

The next decade is likely to be a decisive period determining the future course of US-China relations. If China's economy continues to surge ahead while the United States struggles to bring its burgeoning budget deficit under control, the PRC could emerge from this coming decade with the largest GDP in the world. This will have both psychological and strategic significance and could roil the waters of the bilateral relationship.

Recent US attention to East Asia, and particularly to Southeast Asia, is part of a coherent US policy approach in East Asia that seeks not to contain China but to restore confidence in the region. The United States, despite its budget difficulties, is truly committed to maintaining a robust US presence in both northeast and southeast Asia. Not surprisingly, this flurry of US activity is causing many Chinese to see the United States as challenging China in its own backyard. In reality, the situation is more complex.

China labors under a unique handicap in determining its regional foreign policy. It is the only country in the world that has so many contentious territorial disputes with bordering countries. China's instinctive desire to use its growing strength to be more assertive in defending its territorial claims only brings it into confrontation with its neighbors, which plays into the hands of the United States. The net result is that for a time China struggled to find the right response to the Obama administration's policy of rebalancing in East Asia.

Since last summer, China has moved toward an effective counter-strategy marked by a pattern of less assertive behavior, high-level meetings with leaders in Southeast Asia, and agreements with some of the other claimants to disputed territory over managing tensions. It also reaffirmed Deng Xiaoping’s concept of “setting aside disputes and pursuing common development.” This new approach is symbolized by Beijing’s establishment of a nearly $500 million China-ASEAN Maritime Cooperation Fund in November 2011. The size of this fund highlights the scale of the economic resources that China can draw on to shore up its regional approach, in sharp contrast to the United States.

In short, China has adopted the Bismarkian strategy of seeking to persuade the countries around it who feel threatened by China’s rapid rise that their interests will be better served by cooperation with China than by coalescing against it. Nevertheless, the nationalistic pressures unleashed by China’s enhanced claim to global leadership have the potential to undermine the domestic base for Beijing’s current approach.

Nevertheless, Beijing’s diplomatic nimbleness means that the United States must constantly calibrate its approach to the region. In particular, the United States should be careful not to overplay its hand. China's more assertive behavior following the 2008 financial crisis did indeed increase the desire of Beijing's neighbors for the United States to remain engaged to play a balancing role. But now, the very countries in Southeast Asia that welcome renewed US attention to the region are worried that the United States may be going too far in provoking China by trumpeting US determination to pivot back into East Asia.

US credibility is also affected by the discrepancy between the more vigorous US posture in Asia against the backdrop of an underperforming US economy and a political system that seems incapable of addressing domestic problems effectively. These factors strengthen the image of the United States as a declining power. America's closest friends and allies in the region are worried that the United States may become distracted by its domestic difficulties and lack the staying power to counter China's rise by other than military means.

Such considerations underscore the fact that successful US reengagement in Southeast Asia will place a premium on effective management of the US-China relationship. East Asians want the United States sufficiently engaged to cause China to be more cautious in using its growing power in inappropriate ways. But they do not want the United States to behave in ways that make China a more dangerous neighbor.

Both China and the United States have defined a framework for the relationship that, in principle, should make these challenges manageable. In the two US-China joint statements issued in November 2009 and January 2011, the United States welcomed a strong, prosperous, and successful China that plays a greater role in world affairs, and China welcomed the United States as an Asia-Pacific nation that contributes to peace, stability and prosperity in the region. In terms of declared policy, therefore, the United States is not trying to hold China down, and China is not trying to drive the US out of the western Pacific.

The question for both parties is whether they can adhere to these positions over time as China grows stronger and more influential. Beijing sees itself as again becoming the central player in Asia, while the United States has long been a Pacific power with formal alliances and strategic ties throughout the region. Both Washington and Beijing consider good bilateral relations vital, but their growing strategic rivalry has the potential to evolve into mutual antagonism.

Given these circumstances, China and the United States will not be able to lessen strategic mistrust unless and until they are prepared to address a central question: Is there an array of military deployments and normal operations that will permit China to defend its core interests while allowing America to continue fully to meet its defense commitments in the region? Neither country has yet shown any inclination to begin exploring whether such an accommodation is possible. And yet this is what needs to be done if we wish to avoid seeing history repeat itself.

Can the US afford an arms race with China of indefinite duration? The answer depends on the vigor of the US economy. In the short term, the answer is undoubtedly yes. In every measure of national strength the US has the edge on China. This is likely to remain the case for an extended period of time. But there is no room for complacency. A top priority for the US in facing the challenge of a rising China must be to get its domestic house in order.

We should constantly bear in mind that China's challenge to the United States is of an entirely different order than that posed by the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The USSR never posed a serious threat of overtaking the United States in terms of the size or vitality of its economy. In China’s case, it has for an extended period been advancing in multiple areas that contribute to comprehensive national strength. There is no question that China faces daunting problems in sustaining its rapid growth, but US policy should not be based on expectations that China’s structural weaknesses will prevent it from becoming stronger and more prosperous.

Stapleton Roy is director of the Kissinger Institute on China and the United States. In a career of 45 years he served as ambassador to China, Singapore and Indonesia and was Assistant Secretary for Intelligence and Research at the US State Department. This article is based on his presentation at the first annual conference of the Johnson Center for the Study of American Diplomacy, held in honor of Henry Kissinger at Yale University in March 2012.