Prepare for the 21st Century Exodus of Migrants

Prepare for the 21st Century Exodus of Migrants

NEW YORK: Immigration has emerged as a key campaign issue in the elections in Great Britain, the United States, Germany, France, Austria and India. International migration, while of little demographic consequence at the global level, can be more visible at the national level, impacting population size, age structure and ethnic composition. Nations like the United States, Australia and Great Britain could expect minimal population growth – and in Canada’s case, decline – without international migration.

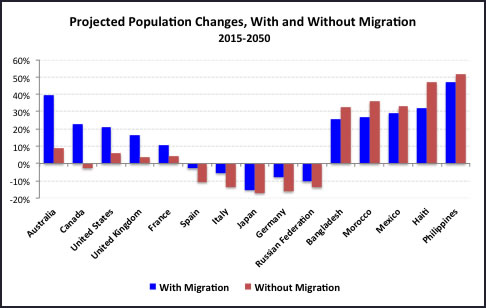

International migration accounts for the dominant share of future population growth in many countries, especially those with low fertility rates, over the coming decades. By mid-century, for example, the projected proportions of population growth as a result of immigration are substantial: Australia, 78 percent; the United Kingdom, 78 percent; and the United States, 72 percent. Without international migration, Canadian population is projected be about 3 percent smaller by 2050. In most other developed countries, including Italy, Japan, Germany, Spain and the Russian Federation, immigration reduces the expected declines in their future populations resulting from negative rates of natural increase, with more deaths than births annually. For example, without international migration Germany’s current population is projected to decline by 16 percent by mid-century; with immigration the projected decline is halved to 8 percent.

In contrast, for many of the traditional emigration countries, such as Bangladesh, Haiti, Mexico, Morocco and the Philippines, their future populations would be decidedly larger in the future without the outflow of their many migrants. Haiti’s population, for instance, is expected to increase by 32 percent by 2050, without emigration its population is projected to increase by 47 percent.

Population projections depend on assumptions regarding future levels of fertility, mortality and international migration. Of those three fundamental components of population change, it is widely acknowledged that the most difficult to anticipate is international migration. Despite the challenges, however, explicit assumptions are necessary for good planning as all are critical ingredients of demographic change for many countries.

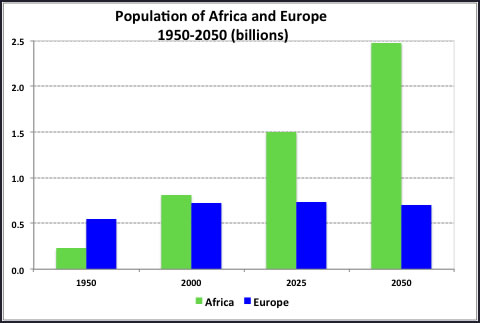

United Nations population projections generally assume that international migration trends for most countries, excluding the movement of refugees, will be similar to recent levels, if stable, until mid-century and subsequently decline. Such assumptions may be politically palatable as well as statistically defensible for governments of major sending and receiving migration countries. However, assumptions based on the recent past likely underestimate future migration because they fail to sufficiently capture the powerful demographic, economic and sociopolitical forces increasingly driving international migration flows in the years ahead. While the older populations of many of the migrant receiving countries are growing slowly with some even declining, the younger populations of the migrant sending countries are growing rapidly. This critical demographic differential is most evident in a comparison of the populations of Europe and Africa. Up until the close of the 20th century Europe’s population exceeded Africa’s. During the 21st century, the demographic relationship is markedly reversed with Africa’s population becoming increasingly larger than Europe’s.

The differences in the economic conditions in migrant sending and receiving countries are substantial. Most workers in developing countries face high unemployment, low wages, few if any benefits and limited opportunities for career development. Housing is often substandard. Educational and training opportunities are limited; health care services, if available, are basic; and most families live at close to subsistence levels. In contrast, living conditions in the wealthier developed countries resemble nirvana, especially to those in poorer distant lands.

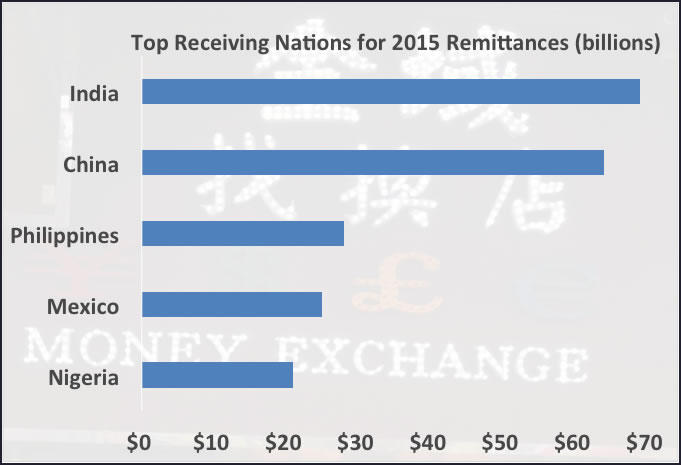

Corroborating the financial benefits and advantages of emigration to the wealthy nations are the huge remittances sent home to families in developing countries, $432 billion in 2015 or more than triple the global total of overseas development assistance. Top recipient countries of recorded remittances are India, $69 billion; China, $64 billion; the Philippines, $28 billion; Mexico, $25 billion; and Nigeria, $21 billion. As a share of GDP, however, the top recipient countries are Tajikistan, 42 percent; the Kyrgyz Republic, 30 percent; and Nepal, 29 percent.

Failing or fragile states, troubled by ineffective governance, political instability, violence and armed conflict, are also driving increased international migration flows. Among the top 25 failing states – many are war-torn countries including Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Iraq, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria and Yemen. By the end of 2015, the major sources of refugees under the mandate of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, accounting for two out of three of refugees, were Syria, 4.9 million; Afghanistan, 2.7 million; Somalia, 1.1 million; South Sudan, 800,000; and Sudan, 600,000.

In addition to international migration’s potent push factors, strong pull factors operate in many migrant-receiving countries. Both the private and public sectors frequently look to migrants to resolve labor shortages and maintain wages. In addition to highly skilled migrants, employers seek unskilled, low-wage migrant workers to perform tasks and provide services that the native populations largely avoid – in the agriculture, fishing, health care and construction industries.

An instructive approach to anticipating future migration levels is to consider people’s intentions, plans and behavior. Based on international surveys, the number of people indicating a desire to immigrate to another country is estimated at about 1.4 billion, far larger than the current 244 million migrants worldwide.

Among those wishing to migrate, an estimated 100 million report planning to migrate in the next year and 40 million are estimated to have taken steps necessary for migration, such as obtaining travel documents, visas, financial resources and more. Again, such estimates of likely migrants in the near term are substantially greater than the world’s current level of nearly 6 million migrants per year.

The leading destination of potential migrants is the United States followed by the United Kingdom, Canada, France, Germany and Australia. If those taking steps necessary to migrate were to immigrate to desired destinations, the result would expand UN-projected annual numbers for major migrant-receiving Western countries by more than tenfold.

Future migration levels may turn out to be similar to those of the recent past, as assumed by official population projections. However, such assumptions seem doubtful in light of sizeable demographic, economic and governance differences between migrant sending and receiving countries as well as the reported intentions of many to immigrate.

Growing numbers of people – many unauthorized migrants, refugees and asylum seekers – are on the move. Despite considerable risks and shrill opposition in many receiving countries, migrants boarding boats, trains, trucks, and even walk, determined to find another home.

Given those circumstances, it would be prudent and useful to prepare alternative projection scenarios for international migration. Foreign aid and development, as well as ending conflicts, could reduce migrant flows, and assumptions need not be as enormous as estimated by some. Still, larger numbers should be envisioned and seriously considered by governments and international agencies.

Ignoring the likelihood of large-scale international migration flows in years ahead may be politically expedient, especially for those advocating tightened borders and restrictions for migrant admissions. Doing so, however, is shortsighted, misguided and ill advised – and will undermine policy development, responsible planning and program readiness for the international migration exodus in the 21st century.

Joseph Chamie is an independent consulting demographer and a former director of the United Nations Population Division.

Comments

In Australia demographic forecasters have hopelessly underestimated the rate of population growth. In 2003 their estimates were for a population of 26 million by 2050 a growth of 4.7 million. Three years later this was upped to 28.1 million, then 34 million 2 years later, then 36. 8 million and now 38 million, a figure bound to be too low because it does not take into account the change in visa rules that allow primary school students and their guardians to apply to study in Australia. Interestingly enough one of our most vocal (and error prone) demographers Prof. Peter McDonald joined the attack on the then PM Julia Gillared after she rejected the previous PM's idea of a Big Australia by reducing immigration and calling for a crack down on rorts in the temporary skilled visa program. He claimed that that the racial implications of Ms Gillard’s remarks were “nasty stuff" and “undermined the system".

Unfortunately open borders are being promoted in order to maintain constant population growth; the 'developed world' ideas managers are not really trying to avert this disaster. "If those taking steps necessary to migrate were to immigrate to desired destinations, the result would expand UN-projected annual numbers for major migrant-receiving Western countries by more than tenfold," writes Joseph Chamie, (this Yale article). That would mean immigration at about 2.5m every year in Australia, or about 10% of Australia's current population. This would have Australia's population doubling in the following 10 years, but of course it would then grow faster and faster, due to compounding natural increase and an increasing population base! 75% of Australia is rangelands and arid desert, similar to North Africa. Australia's undemocratic immigration-engineered population growth rate is already overwhelming its infrastructure. The increased demand means money for developers, but increased prices for most people. Reading Chamie's article makes me again wonder whether modern economics has actually confused people with dollars.

Joseph Chamie first launched these ideas via the UN in 2000, “Replacement Migration: Is it a Solution to declining and Ageing Populations,” 6 January, 2000 and for the final report, released on 22 March 2000. At the time it was received with laughter from demographers in Europe, but taken seriously by absurdist economists in the Anglosphere. The absurd is now becoming reality, constantly promoted in the corporate press. The process promoted is more dangerous than Hitler, because demographic inertia has a life of its own and engineering population age-cohorts to balloon is nuts.

The idea is to constantly increase world population numbers in guise of maintaining youth cohorts at the same unusual proportional levels as they were at the time of the 'Baby-boomers'. This plan would lead to grotesque distortions in demand and individual survival that business people, naive about the numbers, imagine would keep them rich. Indeed, a small number of elites and corporates who control resources, would become even richer than today - for a short time - but at these rates of growth, the world's capacity to feed itself and remove waste would collapse - very quickly.

As French Demographer Henri Leridon wrote in 2000 about Chamie's "Replacement Migration solution", the numbers would be “frankly extravagant”. They would involve 12.7 million immigrants per annum in Europe, amounting to a total of 700 million from 2000 to 2050, “for an initial population of 372 million inhabitants; 1.7 million per annum in France, that is to say, 94 million in 55 years – one and a half times the initial population...”. He added, “As for poor South Korea, which is included in these projections for reasons that remain a mystery, South Korea would have to take in more than five billion immigrants over the period, and the population density there would exceed 62,000 inhabitants per square kilometer in 2050.”

It is never clear to me whether Chamie is advocating this horror-scenario or trying to warn the world. Either way, he is failing, because most people simply have no idea of the numbers and those who suspect the numbers, cannot believe that their 'leaders' would do this to them. As an evolutionary sociologist who writes about human and other species population dynamics (Demography Territory Law: The Rules of animal and human populations), I find it remarkable that the economists and demographers most seen and heard in the mainstream media, think that disporportionate youth cohorts are a good thing. They seem to be operating as if the laws of nature had been entirely suspended by the laws of finance. If anyone wants to read more about Henri Leridon's analysis in English I have republished parts of his texts most recently in an article called, "The plan to flood Europe with migrants - UN 2000 report," at https://www.candobetter.net/node/5579

With regard to the population growth in the 'developing world', the replacement of traditional economies with cities is the cause of overpopulation and this has been made possible by modern transport. It has brought greatly increased fertility opportunities to peoples and tribes that were previously limited by endogamous restraint in viscous populations. Everyone once lived in viscous populations. Immigration factors have been magnified by new transport technologies, all over the world. We need to preserve and promote viscosity everywhere we can, not more and more cities and population movement. If turbo-charged capitalism had not got control of world ideation, this might be possible.