Putin at 20

Putin at 20

NEW YORK: Just over 20 years ago, post-Soviet Russia’s first president, Boris Yeltsin, handed the reins of power over to Vladimir Putin, then a virtual unknown outside the Kremlin, with the charge to “take care of Russia.” As Putin concludes his successful two-decade rule, he must consider the prospect that the best way to extend his legacy is by relinquishing power.

Western governments and commentators in 1999 fumbled for answers about who Putin was and what he intended for Russia. Was he a pro-Western reformer or a budding anti-Western authoritarian leader? Would he master Russia’s unruly politics or become a puppet of other forces? No one knew for sure.

Putin himself had already offered answers in a brief document released shortly before he assumed power. Russia at the Turn of the Millennium outline his mission to restore Russia to greatness on the basis of traditional Russian values, which he identified as patriotism, faith in a strong state, great-power aspirations and spiritual unity. Russia would abandon the 1990s effort to adopt the political and economic model of another country such as the United States. Time was short, he warned, as Russia was on the verge of falling into the second or third rank of world powers. He insisted that Russians had to rely on their own internal resources and ingenuity. No other country, he concluded, was prepared to help.

.png)

The task was daunting. During the 1990s, Russia endured a profound systemic crisis and national humiliation unprecedented for a major power not defeated in a great war. The economy collapsed by some 40 percent. The mighty Red Army withered into a shadow of its former self. Ambitious regional barons and rapacious oligarchs sucked power and authority out of the Kremlin and divided among themselves the lucrative assets of a nearly totally nationalized economy. Western powers, the United States in the lead, shamelessly interfered in Russia’s internal affairs, ostensibly with the goal of assisting its transition to a free-market democracy, and their representatives roamed freely about its traditional sphere of influence in Eastern Europe and Eurasia with little regard for Russia. NATO began to expand eastward, admitting the first wave of erstwhile Russia allies – Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic. Many Russians feared Russia would collapse as the Soviet Union had a decade earlier.

Two decades later, the outlook could not be more different. Putin restored the Kremlin’s power and authority, taming the barons and oligarchs and eviscerating other state institutions, political associations, and the independent media in the process. He drastically reduced Western influence over domestic affairs, cracking down on foreign-funded civil society organizations and individuals, ending Western assistance programs and sending Western advisors home. He rebuilt the military, using it to great effect in Ukraine and Syria. Deservedly or not, Russia has gained the reputation of a power that can influence elections in well-established Western democracies, the United States included; set the diplomatic stage in the Middle East; defend dictators, such as Syria’s Bashar al-Assad and Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro, from Washington’s wrath; and effectively eroded the US-led liberal world order. Russia is once again feared and respected on the global stage.

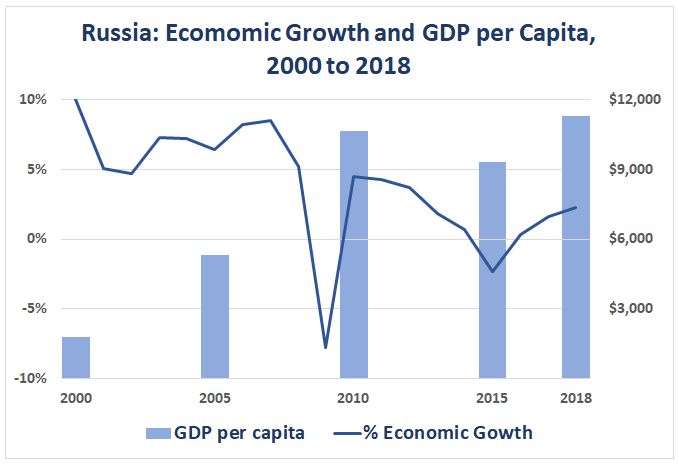

Putin deserves major credit for this reversal of fortunes. For 20 years, he has displayed unrelenting political will and tactical virtuosity in consolidating power at home and exploiting opportunities abroad as they arise in pursuit of his goals. But he has also been incredibly lucky. In his first years in power, soaring oil prices were a godsend, enabling him to raise living standards, reward his allies, buy off the discontented, pay off foreign debt to end Western tutelage over Russia’s finances and rebuild Russia’s capacity for independent action.

More recently, he has benefited from the disarray and loss of confidence in the West, triggered by long wars in the Middle East and the 2008 debt crisis. These challenges opened up power vacuums for Russia to fill in the Middle East and beyond, magnifying Putin’s reputation. Even strategic alignment with a rising China – now reinforced by American pressure on both countries – was a stroke of good fortune given the long history of troubled relations.

But it’s not yet mission accomplished for Putin. Two major tasks lie ahead:

First, Putin must lay the foundations to sustain Russia’s regained global standing over the long term. Success is not foreordained, given Russia’s current stagnant economy and lagging investment in cutting-edge technology, especially compared to that of China and the United States, the two global powers by which Russians evaluate their success. Depending on the measure, Russia’s economy is between one-eighth (nominal) and one-sixth (purchasing power parity) the size of China’s and one-twelfth (nominal) and one-fifth (PPP) that of the United States’. The gap is widening at current growth rates. China and the United States each spend more than twice what Russia does on research and development as a percentage of GDP.

Putin knows he must reinvigorate the economy. So far, he has sought to do that by making the current system function more efficiently rather than through reform and modernization, as advocated by his senior economic officials. He has shied away from reforms in large part because Russia’s oligarchic structure, with its tight intertwining of political and economic power, would compel him to rein in the outsized economic fortunes of loyalists on whom his political power rests. In this regard, the fate of the last Russian leader to undertake this task, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, is a cautionary tale. Not only did Gorbachev fail to revive the Soviet Union, he lost his power and his country. Nevertheless, modernization cannot be put off for long without eroding Russia’s position as a great power.

Tougher still but necessary is the second task of Putin leaving the political stage. He will have finally succeeded only when Russia is capable of prospering and projecting power without him at the helm. But in the absence of laws and traditions to ensure safety and well-being out of power, no Russian leader has relinquished power freely, with the possible exception of Yeltsin. The historical record remains unclear as to whether a sick, unpopular Yeltsin decided on his own to resign or was forced out in a soft palace coup by men determined to secure their own positions.

Putin must decide whether to run that risk by 2024 at the latest when the constitution mandates that he step down as president, but not necessarily give up power. Moscow is already rife with speculation on how Putin will hang on to power – by amending the constitution to remove the presidential term limits or by forcing Belarus into a full-blooded political union, which he could then lead, or some other stratagem. Few believe that he will simply hand power over to even a handpicked successor. Putin has done nothing to clarify his intentions.

Yet, for Russia’s sake, he should hand over power. No matter what his accomplishments, 20 years is a long time at the peak of power. Long-serving leaders inevitably lose their drive. They become more isolated, less attuned to the rising forces swirling around them, less open to change. Indeed, Putin may discover that only by relinquishing power can he open the path to the modernization needed to ensure Russia’s long-term survival as a great power.

Thomas Graham, a distinguished fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, was the senior director for Russia on the National Security Council staff under President George W. Bush.

Comments

Kind Attn : Mr Thomas Graham, Dist. Fellow

Dear sir,

After a very long time, I have gone through a Clear, Factual, Pointed and In - depth assessment of Mr Putin's rule in Russia and its future consequences for Russia and the World.

Thanks & Regards

Mahendra K Shukla

India