Replacement Fertility Declines Worldwide

Replacement Fertility Declines Worldwide

NEW YORK: The fertility rate, or the average number of births per woman, is typically of little concern for government and business leaders until it brings about population decline, shrinking the labor force and substantially increasing the proportion of elderly. Decline begins when fertility falls and remains below the replacement level of about two births per woman

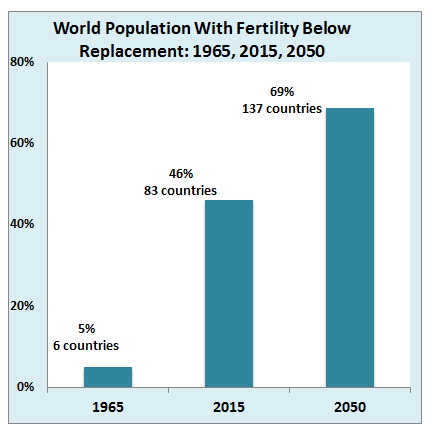

A half-century ago six countries – Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Japan, Latvia and Ukraine, 5 percent of the world’s population – reported fertility rates slightly below replacement level. Today a record high of 83 countries, representing about half of the world’s population, report below-replacement level rates. By 2050 more than 130 countries, or about two-thirds of the world’s population, are projected to have fertility rates below replacement level.

Many countries manage low fertility rates for decades. The fertility rates of Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan and the United Kingdom, for example, have been below replacement level for more than 40 years. Most European countries have remained below replacement for more than 25 years. Japan in 2017 had the fewest births since official statistics began in 1899.

Future rebounds in fertility cannot be ruled out, but once fertility falls below replacement level, the trend endures. This pattern has been especially evident in countries where fertility has declined to 1.6 children per woman, including Canada, China, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Japan, South Korea and Russia. Among the factors responsible for below-replacement fertility levels are lower child mortality rates, widespread education, increased urbanization, improvements in the status of women including increased employment and economic independence, availability of modern contraceptives, delayed childbearing as well as the decline of marriage and pension systems and increased costs of childrearing. Available demographic evidence suggests these factors will persist and become widespread globally.

In many developed countries significant numbers of women remain childless. The percentage of childless woman aged 40 to 44 years in the United States, for example, doubled from 1976 to 2006, reaching over one-fifth of women. In 2010 no less than one-fifth of women aged 40 to 44 years were childless in Austria, Germany, Japan, Spain and the United Kingdom. Reasons for not having children vary, often encompassing personal, financial, political and environmental considerations.

Among women having children in developed countries, most have one or two children, with a smaller number choosing to have three or more. Countries with the lowest proportion of births after a second child in 2015 include Spain, 11 percent; Greece, 13 percent; and Italy, 14 percent. In most OECD countries, less than one fifth of births represent children beyond a woman’s second child. A notable exception to this pattern is the United States where 30 percent of births represent children beyond the replacement level.

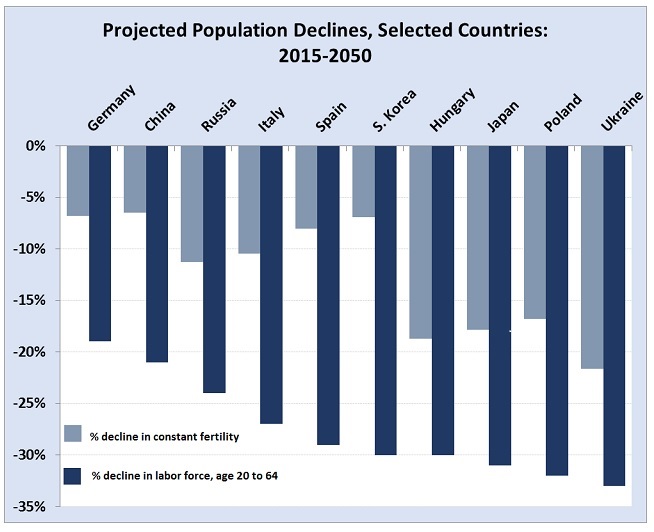

Since the start of the 21st century, close to 20 countries have declined in population size and are aging rapidly due to low fertility levels. If current below-replacement fertility rates remain unchanged, populations of 40 countries, including China, Germany, Japan, Russia and South Korea, are projected to be smaller by mid-century. Even if fertility rates were to increase modestly, as assumed by a United Nations projection, the populations of those countries are still expected to be smaller by 2050.

More challenging for governments are projected declines in labor-force populations aged 20 to 64 years. Working-age population declines exceeding 20 percent are expected in many countries, including some of the world’s largest economies, such as China and Japan. Expected population declines are accompanied by rapid population aging.

As a result of below-replacement fertility and increased longevity, populations are becoming the oldest in human history. Increases in the proportion of elderly, those aged 65 years and older, are projected to be substantial and widespread. By mid-century, for example, the elderly are expected to account for more than a third of the populations of Germany, Italy, Japan and South Korea. The relative increase of the dependent older population has repercussions, especially regarding retirement ages, pensions, taxes, voting, health expenditures and elder care.

Some political leaders acknowledge the challenges. Paul Ryan, outgoing speaker of the US House of Representatives pointed to a need for higher US birthrates in this country: “baby boomers are retiring, and we have fewer people following them in the work force.” At the start of the year, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe labeled Japan’s dwindling birth rate alongside an aging society as a “national crisis.” Sultanka Petrova, deputy labor minister of Bulgaria, described the country’s projected decline in its working-age population as “a social and economic bomb that will explode unless we take adequate measures.”

Commenting more circumspectly, President Xi Jinping of China, which abandoned its one-child policy, said in his report to the 19th National Congress: “We will work to ensure that our childbirth policy meshes with related social and economic policies, and carry out research on the population development strategy.”

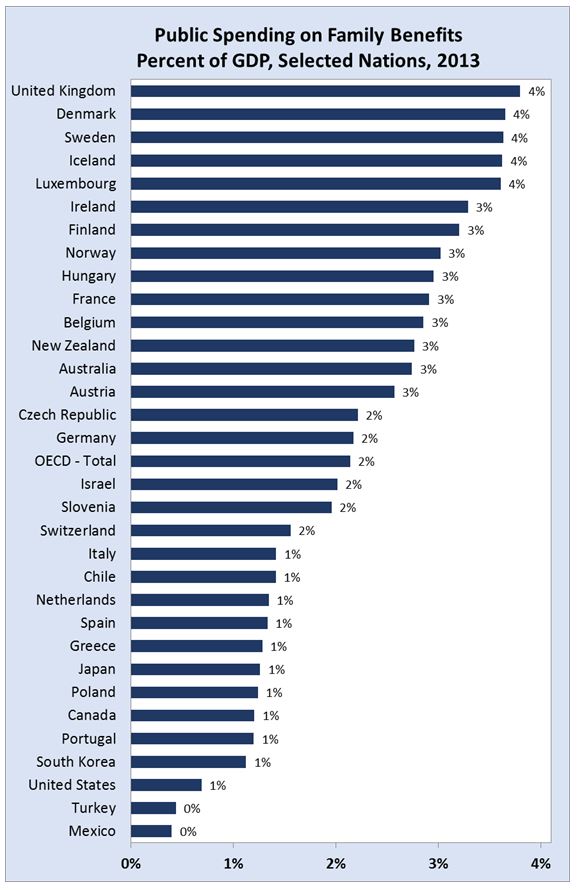

Nearly two out of three countries with below-replacement fertility have policies and programs to raise birthrates. In addition to public programs promoting marriage, childbearing, parenting and gender equality, governments try various incentives to raise fertility rates including baby bonuses, family allowances, maternal and paternal leave, tax breaks, flexible employment schedules and family-friendly work environments. Costs of those incentives can be substantial. While in some countries such as Mexico and the United States public spending on family benefits is well below 1 percent of GDP, in other countries, including Denmark, France, Sweden and the United Kingdom, family benefits amount to 3 to 4 percent of GDP. Some European countries, including France, reduce their comparatively generous family benefits to scale back budgets.

Pronatalist incentives may encourage some couples to have additional children or start families earlier than planned. Such measures by and large tend to be costly, the impact modest at best, and insufficient at increasing fertility rates above replacement levels. Powerful forces overwhelm pronatalist policies, especially economic uncertainty related to automation and the decline of good jobs and the high costs of having children.

Some governments rely on selective immigration to maintain the size of their workforce and slow the pace of population aging. However, a United Nations study concluded that current immigration levels cannot offset expected demographic declines and population aging for most countries with below-replacement fertility rates. Countries worldwide increasingly aim to reduce immigration levels and stem record flows of refugees by erecting fences and barriers, strengthening border controls, tightening asylum policies and restricting citizenship. Attempts by regional and international organizations to encourage acceptance of immigrants and growing numbers of refugees encounter fierce political resistance, public opposition and nativistic policies.

To confront decades of below-replacement fertility, governments must adjust to demographic and economic realities rather than simply promote political wishful thinkingabout increasing family sizes, as Viktor Orbán did in May when he blamed diversity and illiberal democracy for shrinking families and a fertility rate of 1.4 children per woman. A significant boost in fertility levels is unlikely, at least for the foreseeable future.

Certainly, below-replacement fertility resulting in smaller populations can lead to benefits including conservation of natural resources, enhanced educational opportunities, higher labor force participation rates, and in some instances higher standards of living. At the same time, however, the expected demographic changes for low-fertility countries pose challenges for economic growth, retirement, social security and health-care systems.

Despite more countries facing population decline and rapid population aging, world population continues to increase, likely reaching 8 billion by 2023, 9 billion by 2037 and 10 billion by 2055. This growth is largely due to the high rates of demographic growth in sub-Saharan African countries, where fertility levels are generally in excess of five births per woman. While the populations of 40 low-fertility countries are projected to be smaller by mid-century, some 25 high-fertility countries, nearly all in Africa, are expected to see their populations more than double by 2050.

For most countries, sustained below-replacement fertility rates promise population decline. Communities that refuse to adjust will only exacerbate the consequences of these powerful demographic trends.

Joseph Chamie is an independent consulting demographer and a former director of the United Nations Population Division.

Comments

That 2050 figure is over-optimistic.

Please note that we are currently adding 85+ million a year and that figure is rising !

Eric

Perhaps this was written cleverly and diplomatically so as not to ruffle too many feathers among overshoot deniers. Maybe this is the best way to bring them around - not necessarily to embracing population decline, but at least to stop fighting it. Still, from someone so knowledgeable as Chamie, as I read I kept looking for the acknowledgment that while there are challenges associated with contracting population, the fact is that continued growth of human population will lead to severe crises and possibly collapse of human civilization. This warrants more than a mere mention near the end as a "conservation of natural resources" benefit. Avoiding catastrophe is a benefit that trumps all the challenges, so we should embrace, celebrate and pursue population contraction in all parts of the world. We are a LONG way from the day we might need to worry that we're procreating too little to preserve our species. We are much closer to procreating too much for our species to survive.

Dave Gardner

Host of the GrowthBusters Podcast

Director of the Documentary, GrowthBusters: Hooked on Growth

www.growthbusters.org

It's so sad to read such an eminent demographer repeating the fallacies of ageing catastrophists - while neglecting the rapidly escalating environmental strains of population growth. Working age proportion does not equal workforce. Chamie even mentions that ageing might lead to higher workforce participation, but fails to acknowledge that this makes the whole 'working age proportion' fixation a rouse. Among OECD countries, there is no relationship between extent of ageing and proportion of people employed. Nor has any country seen a demonstrable decline in workforce due to ageing: it has not reduced employment, but UNemployment. Nor is ageing going to continue apace until there is insufficient supply of potential workers - it is a self-limiting process. That economic models persistently treat age-specific workforce participation as a given, not impacted by choice of demographic scenario, is quite against their own theories of market forces. They are all rubbish, and should be called out as such by demographers.

Beyond that, it is irresponsible to suggest that boosting births or immigration can lessen the burden of ageing, at anything like the scale at which they increase the burden of population growth. The infrastructure costs alone dwarf any diminution of pension bill, even if we assume that the future retirees in a shrinking population and those in a rapidly-growing population will have had equal chance of saving for retirement, despite the latter having lower wages, more unemployment, higher mortgages and more government austerity due to infrastructure bills. Assuming they can maintain food and energy security, and successfully avoid a climate catastrophe. In what inventory of humanity's challenges does ageing even rate a footnote?

Death camps, concentration camps, massive divides in wealth and education. They got the civilization they deserved.

There is really one reason and one reason only for why this is taking place and it's the gigantic white elephant in the room that NO ONE wants to talk about, and it’s very simple: men have NO INCENTIVE WHATEVER to get married, have kids, and settle down with women in the West. In fact, the numbers indicate that of men will be on the losing end of EVERYTHING associated with procreation and marriage and women get all of the benefits. I know this from first-hand experience. Don't try the feminist dodge on this, or dance around it. Feminist and gender activists have finally gotten their wish: men are in full retreat from associating with women and more and more men in the age category of 18-30 won't even consider marriage as an option. So, for all you "can't figure out why this is happening" types out there--mostly 35 to 50 year-old--bitter angry, feminist women who can't understand why men won't marry them and have kids are reaping what they have sown. Fifty years of feminism and full-blown war against masculinity has fully backfired on women. So here is my battle cry: women out there! Enjoy growing old bitter, wrinkled, and childless. I also suggest that you start your cat menagerie now--because for most of you, that's the best you’re going to do. More men every day are ingesting the red pill and taking Timothy Leary's advice "Tune in, turn on, and drop out." It's just that in this case applied to marriage, women, the courts, and society's sick and perverted war on men. Yes, I said it: war on MEN! Real, masculine, self-respecting, educated, attractive men at their peak of earning potential and virility are writing off marriage and kids. There is absolutely NO reason to gamble with your future as a man that way--a man literally has better odds to win at craps in Las Vegas than to win in the marriage lottery. So, top off your whine glasses ladies, and drink of the bitter dregs of that which you have authored: feminism has accomplished its goal and men are checking out. Now, ask yourself honestly: do you feel better now that you got what you wanted??? Or worse?