A Rising New Force in World Public Opinion

A Rising New Force in World Public Opinion

MUMBAI: The recent meeting of the World Social Forum (WSF) in Mumbai, India, was a big step forward in the steady rise of a global anti-capitalist movement. Over the past five years, the WSF has grown from a relatively small group of economic dissidents to a huge yet decentralized annual gathering of over 100,000 people.

There are three moments of origin in this story. The first was the very successful mass protests at the Seattle meeting of the World Trade Organization in November, 1999. A large group of mostly U.S. protestors - an unlikely coalition of AFL-CIO trade-unionists, environmental activists, and anarchists - succeeded in scuttling the meeting. Two months later, in January, 2000 at Davos, a group of some 50 intellectuals from around the world tried a different tactic, organizing an "anti-Davos at Davos," seeking to get anti-neoliberal arguments a world press. And in February, 2000, two Brazilian leaders of popular movements, Chico Whitaker and Oded Grajew, went to Paris to talk to Bernard Cassen, a journalist and the president of the anti-globalization organization called Attac-France. The two Brazilians suggested to Cassen that they join forces and launch a world meeting that would combine mass protest and intellectual analysis. They convened this in Porto Alegre, Brazil, at the same time as the 2001 meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos. They called this the World Social Forum, and Cassen said the object was to "sink Davos."

Porto Alegre in 2001 expected some 1500 participants. Some 10,000 came. The bulk of the participants in 2001 were from Latin America, France, and Italy. The basic principles of the WSF were that it was an "open meeting place" for "groups and movements of civil society that are opposed to neoliberalism and to domination of the world by capital and any form of imperialism." Its theme was "another world is possible." It was a "process," not an organization. It would not take positions as such, or make proposals for action, but it might generate such positions and proposals by some or all of those taking part in the WSF. It was "plural, diversified, non-confessional, non-governmental and non-party" and acted in a "decentralized fashion." In short, there was to be no hierarchy or organizational discipline.

The formula was original and quite different from the historic antisystemic movements, including Communist and other "Internationals." And it caught fire. The second meeting at Porto Alegre attracted 40,000 participants, including now a large group from North America. The third, in 2003, had 70-80,000 participants. Every conceivable kind of movement - reformist and revolutionary, every variety of oppressed or marginalized persons, the Old Left and the New Left, social movements and NGOs, came. So did an increasing number of political figures. The world press paid increasing attention.

But there were problems. The three biggest ones were: (1) a tension between those who insisted on retaining the formula of an open forum and those who wished to see the WSF become a "movement of movements," perhaps eventually another "International"; (2) an inadequate degree of participation from Asia, Africa, and east-central Europe; (3) debates about the internal structure and the funding of the WSF - how democratic and how independent was it as a structure? All three problems were tested at the Mumbai meeting, the first to be held other than in Porto Alegre.

The concept of the open forum is seen by the original founders as the key element that provides the strength of the WSF. They argue that any deviation from that formula will lead to exclusions and turn the WSF into one more sectarian movement. To guarantee the openness of the forum, the charter of principles had barred "party representations" and "military organizations." Nonetheless, both parties and guerilla movements come anyway, through front organizations.

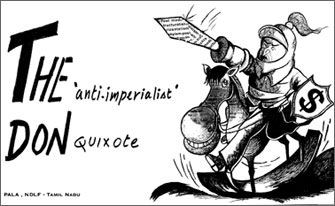

When the Forum moved from Brazil to India, the Indian organizing committee dropped the provision about parties. Still, the proscription against violence led to a split among the Indians. A small Maoist movement organized a counter-Forum, called Mumbai Resistance-2004, on grounds across the road from the WSF. And they denounced the WSF as a combination of Trotskyites, Social-Democrats, reformist mass organizations, NGO's financed by transnationals - in short, a stalking-horse for quietism and counter-revolution. They specifically attacked the concept of the open forum (merely a talk show, they said), the slogan (not "another world," but socialism as the objective, they said), and the financing of the WSF (the fact that some money came from the Ford Foundation).

But Mumbai Resistance proved to be a minor sideshow, stimulating some good discussion in the WSF but attracting maybe 2% of the numbers. As for action by the WSF, many pointed out that the world demonstrations of Feb. 15, 2003 against the war in Iraq, were inspired and organized by WSF participants. So, in the end, everyone seemed to agree that WSF should retain the concept of the open forum but perhaps find some way to accept and institutionalize groups that wished to take common actions.

The wish to expand the geographic scope of the WSF was behind the move to Mumbai, and it was a spectacular success. In 2002, according to the chief Indian organizer, not 200 people in India had even heard of the WSF. In 2004, hundreds of organizations, and more than 100,000 Indians alone attended it, coming from every conceivable social group - at least 30,000 dalits (untouchables), adivasi (tribal peoples), and women everywhere.

The WSF will return to Brazil in 2005 and is planning to go to Africa in 2006. Finally, the internal structure of the WSF was a subject openly debated. An international council had been founded in 2002, with some 150 members, all co-opted. It is broadly representative, but certainly not elected. For were it to be elected, the WSF would become a hierarchical structure. But is this "democratic"? The international council makes real decisions - where the meetings are held, who will speak at the plenary sessions (the "stars"), and who may or may not be excluded from attendance. To be sure, most of the sessions are organized from the bottom up. In Mumbai, there were 50 or so such simultaneous "seminars" at every meeting-time, all in effect autonomous. In the sessions analyzing the structure of the WSF, the push was for more openness of decision-making. And all this, without turning the WSF into a hierarchical structure. Not easy, but at least publicly debated.

One should not miss the evolution of the thematic emphases. At Seattle, the drive was to stop the WTO. After Cancun in 2003, the WTO has receded as a major threat. Indeed, the WSF is still fighting neoliberalism and has made a real difference in that the governments Brazil and India are pushing a different line on global capitalism. The Davos gathering was hardly mentioned at this year, but if there was one villain on all the posters this year, it was George W. Bush. The poster of a Pakistani women's organization captured the sentiment: "When Bush comes to shove, resist."

The leading participants in the WSF are aware that riding the WSF is like riding a bicycle - keep going forward or fall off. For the moment, the WSF is riding well.

Immanuel Wallerstein is Senior Research Scholar at Yale University and author of the new book, “Decline of American Power: The US in a Chaotic World.”