The Roots of Anti-Americanism in Germany

The Roots of Anti-Americanism in Germany

Thanks to 24-hour satellite television and all the global news agencies, the Iraq War was a global event. Yet the same event was seen in different corners of the world through different filters, creating more discord than common concern. In certain regards the average European and American witnessed a different war. Whereas images of US POWs and American and British troops advancing through the desert dominated the vision of the average American, pictures of destruction and civilian casualties were far more common in European headlines. And while the media in Europe paid a great deal of attention to the global wave of anti-war protests, the same rallies were paid scant attention in the American media. Underneath the differing vision of the Iraq War lies a complex interplay of history and political cultures of the two sides of the Atlantic. With the exception of Britain, European public opinion on the war was far more homogenous than the government quarrels would suggest.

Whereas most American journalists basically ignored the European media accounts, their colleagues on the other side of the Atlantic constantly referred to the American coverage of the war. Often frontline images carried red subtitles "censored by the US military", and the American war coverage was portrayed as extremely biased, if not outright propaganda. If we leave out the question as to whether the spectrum of European media accounts were truly more objective or not, these developments indicate a sharp decline of European trust in the United States as a responsible international power and in American political culture.

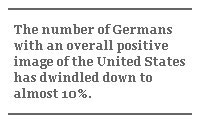

A comparative perspective on the wave of European anti-war protests during the Vietnam era may clarify some of these newly emerging tendencies. Take the experience of Germany - then West Germany. During the Vietnam War students constituted the main bulk of demonstrators, yet still the vast majority of the German population retained a favorable image of the United States. By contrast, in a recent opinion poll the number of Germans stating they had an overall positive image of the United States has dwindled down to almost 10% of the overall population. Secondly - and more importantly - today a large number of Germans understand their demonstrations as protests against the United States as a whole. This is remarkably different from the late 1960s, when German, French, and other youth protesters understood themselves as parts of a global socio-cultural protest movement, which to a certain extent radiated from the American Woodstock generation. Now, in contrast, the European media tends to ignore the widespread opposition to the Bush administration within the United States itself (which certainly raises the issue of objective coverage on the European side as well).

Of course many journalists joined leading intellectuals ranging from Günter Grass to Jürgen Habermas in emphasizing that their opposition was directed at the Bush administration and not at the United States as such. But in a large number of newspaper and TV reports, which represented the entire political spectrum from left to right, the US government's unilateralism was portrayed as a product of American culture, as a consequence of narrow and arrogant political attitudes on the other side of the Atlantic. Many reports pointed towards Christian fundamentalism in the US or the important role of religion in American political discourse as the root causes of the war. Often the implicit message was that America is a democratic culture decaying under the pressure of rising religiosity and interest lobbies.

Whereas there is certainly an aspect of truth in these critical assessments of American political culture, the tendency to describe American society as a rather homogenous, threatening culture, can be worrisome. A tendency to derive a European cultural identity in terms of juxtaposing it against a greatly reduced image of the United States may be in the offing. For example, an article published in a German leftist-liberal news magazine showed two images: one of Bush standing beside a cross "preaching" to military officers and one of protesters in the streets of Berlin. The message of the article was clear: it was Europe - with its tradition of secularism and internationalism - which should stand up against a religiously self-righteous nation trying to impose its sense of mission onto the rest of the world. The article failed to mention dissenting voices within the United States. An even more disturbing example is an article entitled "The Victory of New Europe", which was published in the pages of the rather conservative "Franfurter Allgemeine Zeitung", one of the leading German daily newspapers. Here the author spoke of a "historically unique civilizational richness of the Union, which was sky-high superior to the strange pathos for freedom and liberation of the American government and its fundamentalist prayers." He furthermore depicted the United States as a reduced "democracy run by millionaires and industrial clans" and an "old colony (of Europe) ossified in militarism". He also saw the Iraq War as a signal for Europe to set off to become a second world power to match the United States. To support such an ambition, he reminded readers, one could take heart in Russia's oil fields and France's nuclear weapons. But for the "historically blinded Great Britain," he saw the possibility of "becoming colonized as a US state."

Fortunately, such martial voices remain exceptional in the German and other European public spheres, but their attitudes toward the US reflect the sentiments of a large segment of European societies. All in all they are just extreme examples of the rather alarming and widening gulf between mainstream Europe and the United States. This is accompanied by a growing political and cultural self-righteousness among many European intellectuals and journalists. In fact, while other forms of xenophobia remain taboo, being against American culture and society has now become the only socially acceptable (in some circles even respectable) anti-foreign position in Germany, as well as in a lot of other European societies. For example, a pub owner in Bonn received wide (and in no way negative) news coverage for his boycott of American goods ranging from Coca Cola to Marlboro cigarettes. Needless to say, similar approval of anti-French or anti-Israeli actions would be unthinkable in a society which remains deeply traumatized by its crimes of the past.

In the German context, these negative images of the United States are no doubt projections of the nation's extremely difficult relationships with its own Nazi past on an international level, notably with the US. Until recently the notion of collective guilt made it impossible for Germans to perceive themselves as equal to other Western democracies in a moral, historically normative sense. It would be a tragedy if this perceived moral gap is turned around and embedded into a vision of Europe as a cultural response to an alleged moral decay on the other side of the Atlantic. Indeed, many Germans have learned their lessons from the history of the Nazi era - lessons which the United States has never had to take. With trauma and guilt having replaced triumphalism as the main pillar of national identity, Germans tend to perceive their country to be historically more mature and politically wiser than the United States.

However, a European contribution to the global community can only be convincing if it enacts the very values it acclaims. The justified criticism of the Bush administration's open disdain for world opinion and the due course of diplomacy must not be used to develop a rising notion of European cultural superiority. Rather, European societies now have to prove that they have truly learned from their traumata of the past, that they are both willing and capable of acting on the world stage in historically aware and culturally sensitive ways. For this purpose, a more balanced view of the United States, a shared concern for its anxieties and tensions is the only promising way. Constructing a counter-culture will only take us one step closer to global polarization.

Dominic Sachsenmaier is a research scholar at Harvard University and Scholar of the German National Research Foundation.