Russia and China Test Arctic Boundaries

Russia and China Test Arctic Boundaries

OSLO: In 2016, two seemingly unrelated incidents unfolded in remote and vulnerable parts of Europe. One view might suggest the events, efficiently swept away with quiet diplomacy, counted for little. Another considers the incidents as demonstrating Russia’s and China’s determination to test the outer boundaries of European and American resolve.

There may be nothing new in that such testing happens routinely in Ukraine, the South China Sea and elsewhere. But these two events stand apart for involving the Arctic, the world’s most unknown and unexplored area where melting ice and the opening of shipping lanes present a new, competitive arena among three global powers, China, Russia and the United States.

Last year, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin declared that the Arctic is essential in securing Russia’s future, and, in January, China announced its plans to be a main player in building infrastructure, extracting resources and transporting cargoes along its new Polar Silk Road. Climatologists estimate that at least one Arctic route linking Asia and Europe, now open only during summer, will be reliably ice-free for shipping by about 2050. As routes open, resources will also be easier to extract.

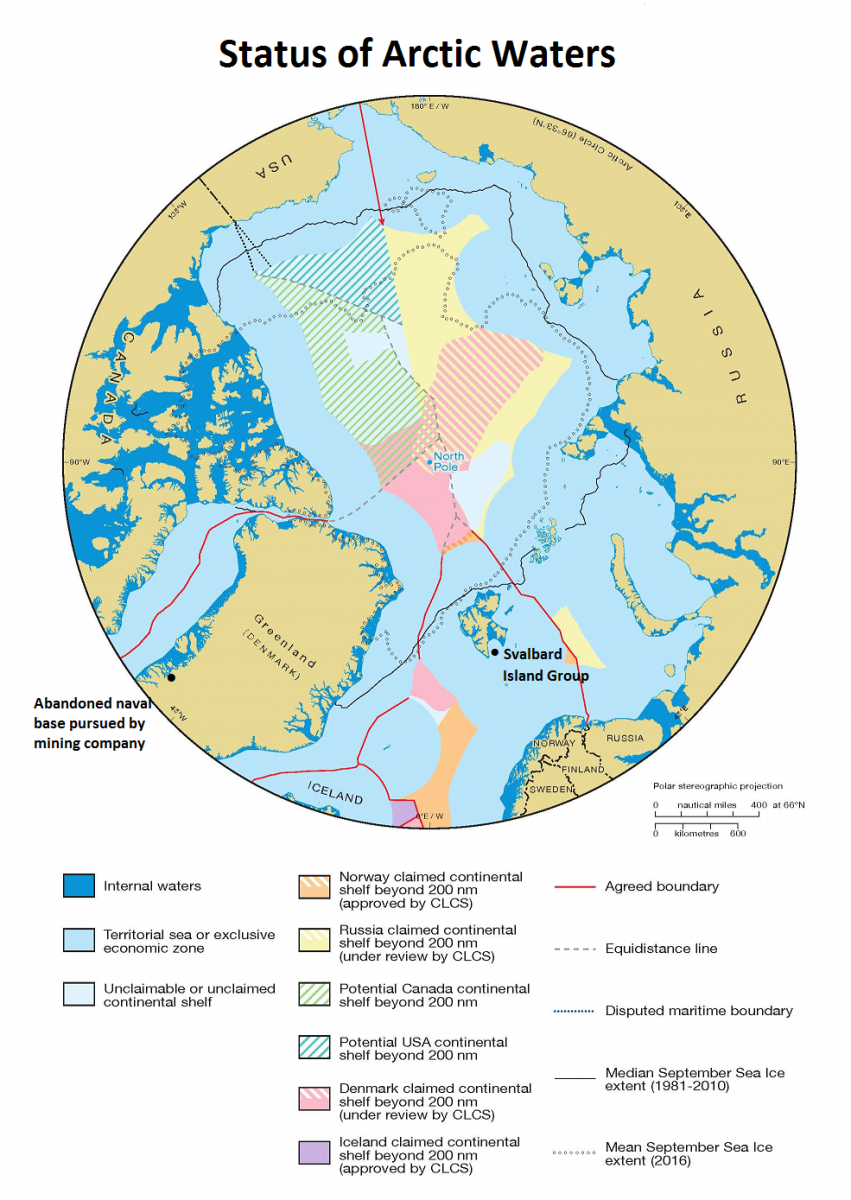

Beijing has no sovereign Arctic territory, while Russia claims more than 450,000 of the region’s more than 6 million square miles and needs China’s money and technology to exploit the resources. The Arctic is estimated to hold 30 percent of the world’s undiscovered natural gas resources and 13 percent of its undiscovered oil. When Moscow came under Western sanctions over Crimea in 2014, Beijing moved in with a substantial investment in Russia’s Arctic oil and gas projects. Unlike the fractious Sino-Soviet pact of last century driven by shared communist ideology, this intensifying partnership is based on transactional business where trade, commerce and secure supply chains may prove a stronger glue holding the two countries together.

The two boundary-testing incidents took place on Norway’s wild and isolated islands group of Svalbard and in the sparsely populated but huge mass of Greenland, the defense and foreign policy of which remain in the hands of its colonial power, Denmark.

Svalbard lies strategically midway between Norway and the North Pole, and until the signing of a treaty in 1920, its sovereignty was disputed among Norway, Russia and others. Norway now has control, and there are 46 signatory governments to the Svalbard Treaty, including China, Russia and the United States as well as countries as diverse as India and Saudi Arabia. All have a right to mine, fish and carry out commercial activities on Svalbard with a red line that no military activity of any kind is allowed.

Yet, in April 2016, a group of Chechen Special Forces flew into Svalbard for a military exercise over the North Pole, including attacking a mock enemy command post and parachuting from planes and helicopters. Use of special forces technically accountable to the Chechen Republic and not the Russian Federation was an interesting nuance, and the operation certainly required a Kremlin greenlight. The Norwegian government moved swiftly, in a low-key manner through diplomatic channels, to stop similar missions on the grounds that “all foreign military activity in Svalbard would entail a gross infringement of sovereignty.”

In the same year, a Chinese mining company tried to buy an abandoned naval base in Greenland, only to find its bid blocked by the Danish government. Again, Denmark handled the matter delicately with no official announcement although the Danish defense community made clear the decision was linked to Denmark’s NATO obligations and security relationship with the United States.

The scenario laid out here is of a weak European economy becoming vulnerable to Chinese control that would threaten Western interests. In Greenland’s case, there is a vibrant independence movement which, if successful, would sever ties with Denmark and remove the autonomous territory from the network of European and Atlantic defense operations. A US airbase is in Greenland’s far north. “Greenlandic politics is increasingly about declaring a wish to become independent,” explains Jichang Lulu of the China Policy Institute at Britain’s Nottingham University. “The prevailing view of successive Greenlandic administrations has been that the only way for the island to afford a state would be a mining boom fueled by Chinese investment.”

The Svalbard and Greenland stories underline a trend running alongside the more overt elements of Russian and Chinese expansion seen in Moscow’s buildup of troops on the borders of the Baltic States and China’s infrastructure-building in the South China Sea along with the Asia-to-Europe Belt and Road Initiative. The starting year for both Russia and China’s expansionist programs was 2012 when Moscow began modernizing its Cold War Arctic bases and Beijing started building bases in a disputed area of the South China Sea. The date, neither coincidence nor conspiracy, has more to do with opportunities emanating from the shifting global balance of power.

China’s work concentrated on seven outposts in the southeastern area of the South China Sea and its existing base on the Paracel Islands to the northeast. The result is that international shipping must travel, as if through a strait, between the militarized Spratly and Paracel islands. “We must recognize a new reality,” says Peter Dutton, director of the China Maritime Studies Institute at the US Naval War College. “Beijing controls this sea.”

At the same time, Russia has been carrying out a similar program with specific focus on an area leading from the Barents Sea into the Atlantic Ocean. Known as its “bastion of defense,” the purpose is to control the maritime gateway from the Arctic to the Atlantic. Svalbard and Greenland are key strategic assets within this theater. Weakened by internal upheavals and with Britain leaving the European Union, Europe once again finds itself caught in geopolitical crosshairs.

Russia has set up a new Joint Strategic Command tasked with protecting Russian interests in the Arctic region while NATO has boosted troop deployment along Russia’s border with Europe and Britain leading a new operation, the Joint Expeditionary Force, designed to act outside of NATO as a fast-reaction force, deployed within hours of any Russian aggression. The operation comprises eight north European countries including Sweden and Finland which are not NATO members. Western defense officials now talk openly about preparing for the fourth battle of the North Atlantic, the earlier ones being the two world wars and the Cold War. “The Northern Fleet and the bastion defense concept present a strategic challenge to the link between North America and Europe,” says Rolf Tamnes of the Norwegian Institute of Defense Studies.

History may partly be repeating itself, and Cold War manuals can justifiably be removed from mothballs and revised. Three elements are very different:

• One is nature of the Sino-Russian relationship in which shared authoritarian values take second place to commercial deal-making.

• Second is China’s money sought by both Russia and its potential Western enemies.

• Third is the Arctic itself, an untested and unfamiliar theater of big power antagonism, where China has a choice of siding with either the United States or Russia – or acting as pragmatic mediator between the two.

If climatologists are right about another 30 years before the ice melts enough for the Arctic to be exploited, these three powers have time to plan carefully and in a way that avoids the horrendous mistakes of last century.

Humphrey Hawksley is an Asia specialist. His next book, Asian Waters: The Struggle for the South China Sea and Strategy for Chinese Expansion, will published by Overlook-Duckworth in June.