The Russian Challenge – Part II

The Russian Challenge – Part II

SINGAPORE: By adopting an atavistic Mother Russia approach in its foreign relations, Moscow is endangering its benefits of being part of a globalized world, casting itself in a position that would prompt hostility and contempt rather than the respect it seeks. A sullen nation-state pursuing nationalistic goals, flexing muscles to impress its neighbors, will scare away international investors indispensable for modernizing and restructuring Russia’s noncompetitive and clumsy industries.

In the prism of the Holy Russia, the men in the Kremlin see three goals:

● Regain respect lost when the Soviet Empire fell apart, aggravating the Russian minority complex nourished by its backwardness compared to Western and Central Europe.

● Remove the feeling of insecurity always uppermost in the mind of Russia’s rulers fearing an invasion from the West. The enlargement of the EU, and even more NATO, is not seen as a step towards “globalization” open also to Russia, but an encirclement of Russia.

● Room to maneuver and look after the Russian minorities living in new nation-states formerly part of the Soviet Empire.

The paradox is that these goals might have been attainable as a partner in the Western system, but being outside, Russia moves further away every time policies are implemented to grab them. In recent months, if not before, the economic costs have been bared. Since May 2008 the stock market has lost almost 60 percent, shaving more than $500 billion from the value of Russian stocks. Foreign investors are pulling back. Not only does Russia lose money, but worse, crucially important technological and management skills slip away.

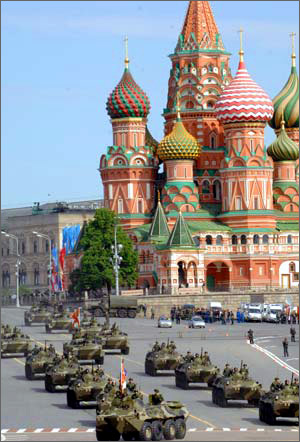

Behind the bravado, Russia is a weak power. Its nuclear arsenal and oil and gas give it leverage in foreign and security policy, but do not constitute a full-fledged panoply of instruments. It will be difficult to deal with in its near abroad as Russia looks for opportunities to assert itself. Adjacent countries will respond by strengthening links with non-Russian powers. Russian circuses are world renowned, but the point that one gets one’s way by rewards, not with punishment and fear, seems to have been lost. When President Dmitry Medvedev recently stated “protecting the lives and dignity of our citizens, wherever they may be, is an unquestionable priority for our country,” he fueled fear and at the same time antagonized China, an erstwhile ally against self-determination for minorities.

Russia’s ‘new’ policy may come to a test in Central Asia, Ukraine and the Baltic States.

The Shanghai Cooperation in Central Asia (SCO) was launched in 2001 with China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan as members. At a summit August 28 Russia got empty words rather than the hoped-for recognition of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. China facing its own separatist movement in Tibet and Xinjiang would not endorse such a step. The four other Central Asian countries had no sympathy for Georgia, but saw the writing on the wall: Russian minorities were used to a destabilized Georgia and the same could happen in Central Asia, for example, Kazakhstan with 4 million ethnic Russians. Instead of maneuvering to marshal support from the SCO countries for its foreign-policy goals, Russia’s ambitions have been disclosed, and the other countries do not like what they see.

The last thing China wants is a resurgent Russia throwing its weight around in Central Asia and the Far East. Geography makes Russia a convenient supplier of oil and gas, but not indispensable, as alternatives are available, albeit at a bit higher price. What is indispensable for China is participation in a well-functioning global economy and the handle is still, despite weaknesses, firmly in the hands of the Western World –definitely not deposited in Moscow.

Ukraine is torn between the West and Russia with a Russian minority of about 25 percent. Strategically Ukraine determines whether Russia is a great power or not. Unquestionably the Kremlin regards it as the prime prize to be won. The US and the EU have since 1991 followed a policy of almost criminal neglect vis-à-vis this pivotal country with 50 million inhabitants. Lucrative offers from Russia then might have lured Ukraine, if not back at least closer to Russia, holding the prospect of a reunion alive. Instead Russia has acted as a bully allegedly labeling Ukraine “not even a real state" and punishing it by closing down energy supplies. By playing on the Russians in Crimea, the Kremlin can cook up a crisis, but as it makes its intentions clear, the more likely it is that the large majority of Ukrainians will stand firm not wanting a reincarnation as underdogs in the Russia universe. A crisis over the integrity of Ukraine’s territory would be a full-blown international crisis with Russia depicted as a clear-cut aggressor, attracting few if any supporters.

The three Baltic States are members of the EU and NATO. Russia can increase its nuisance value; it can stir up trouble among the ethnic Russians, but provided that the Baltics do not overreact, not much more can be accomplished. The Baltics have prospered enormously compared to Russia, making it clear to the ethnic Russians that economically they stand to lose if they rejoin Russia. While the West has been allowed to waffle in Georgia and may also be in Ukraine, a Russian aggression against the Baltics would be against a member of NATO, putting the credibility of the worldwide American system of alliances at stake. NATO members in Northeastern Europe hopefully have understood the need for a future stronger military posture to preempt any Russian wishful thinking.

The wild card in this analysis is the Arctic. Here, a belligerent Russia will directly confront the US, Canada, Denmark and Norway. The last three may find it less palatable to play hardball even if they had the means, which is not the case. This is the one area on the globe where Russia, by concentrating forces, might be able to match the US. The rich natural resources beckoning with the fast melting of the ice cap augurs a nasty game about who takes what. Russia made the first move, announcing in July 2007 its intention to annex the North Pole area. To rub it in, the secretary of Russia's Security Council Nikolai Patrushev stated September 13, 2008: "The Arctic must become Russia's main strategic resource base."

The best thing the US can do in the present circumstances is to realize Russia’s basic weakness, a need for respect. Russia can irritate the US by naval maneuvers with Venezuela and NATO countries with renewed patrols of long-range, but obsolete bombers, but that merely exposes its weakness. Geopolitically Russia is not a match for the US. In its immediate neighborhood, it can rattle the saber, but it’s difficult to envision circumstances as those in Georgia repeating themselves in adjacent countries especially now all parties are warned. Energy supplies can be cut off, but Russia needs Western technology and finance almost as much as the West needs the oil and gas.

Russia has chosen the wrong option and withdrawn into a 19th-century Europe power game. Let it stay there for a while, a long time if it so chooses, while running up high costs. If the Russian leaders insist on keeping their country backwards and underdeveloped, let them.

Joergen Oerstroem Moeller is visiting senior research fellow with the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, and former state-secretary for the Royal Danish Foreign Ministry.