Russia’s Internal Otherness

Russia’s Internal Otherness

TARTU: For Russia, the cost of sacrificing development for the sake of security and international status, a policy that the Kremlin pursued after 2012, is all too obvious and yet ignored. It is time to address the cultural roots of such a self-defeating approach and seek remedy.

Vladimir Putin’s re-election marked a change of the declared priorities of the Russian government. A new attempt at modernizing the economy and social institutions is in the cards. The new cabinet has been instructed to sponsor technological innovation and digital technologies, promote diversification by creating export-oriented industries, and ensure that Russians live longer and better. In acknowledging that technological backwardness ultimately makes the country less stable and secure, Putin follows the path of previous leaders from Peter I and Alexander II to Mikhail Gorbachev. This time, however, Russia is attempting a breakthrough on its own: Former President Dmitry Medvedev’s experiment with the Russia–EU “Partnership for Modernization” is not to be repeated. The current conflict with the West is too intense to allow for another attempt.

The puzzle is why confrontational attitudes to the West are so entrenched in the Russian political class and, presumably, the wider society. It is evident, on the one hand, that achieving a new level of economic development is hardly possible in total isolation. On the other hand, the feeling of insecurity that underlies Russia’s pushback cannot be fully rationalized even if one agrees with the assumption that Western democracy promotion and geopolitical expansion go hand in hand. It is understandable that the top elites see any scenario involving regime change as catastrophic, but mobilizing mass support for sustained multidimensional conflict with the global hegemon requires a deeper sense of disaffection on the part of the larger society.

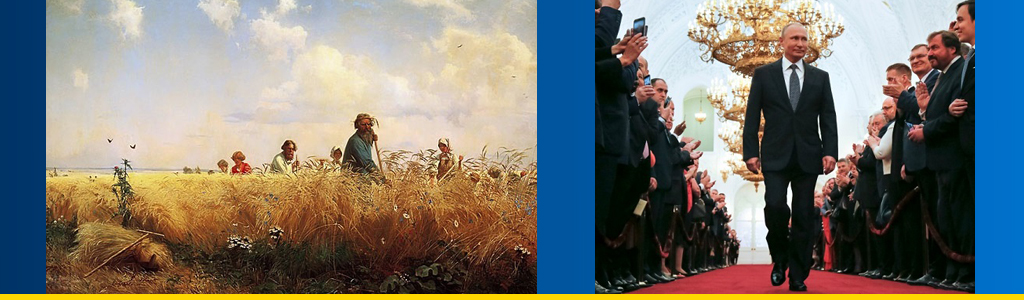

Existing explanations of this phenomenon often emphasize Soviet legacies, such as entrenched paternalism and other forms of cultural difference between Russia and Europe. This approach is hardly satisfactory, as it tends to present Russia as not fully European, thus implicitly evoking centuries-old colonialist stereotypes. An attempt to critically reevaluate those immediately brings to the fore the fact that Russians widely share such attitudes themselves. It is not uncommon for Russians of any social background to imagine their own society as deeply divided between Russian Europeans and native Russians, whose lifestyle is seen as traditional and uncivilized. This imagined cultural divide goes far beyond differences in manners and mores: For liberals and conservatives alike, the “other Russia” embodies everything which is unique about the country and prevents it from integrating with the rest of Europe.

Pro-European Russians would often use derogatory language, describing their own compatriots as backward and barbarian. Lack of proper civilization is blamed for all social and political evils, from shabby staircases and potholed roads to alleged servile submission to the authoritarian rule. It must be stressed, however, that the obsession with the inner barbarian is a universal phenomenon. Conservatives, including Putin himself, also endorse the existence of the native Russian – describing this figure using such terms as “the cultural code,” “indigenous tradition” or just “the Russian soul.”

Traditionalists celebrate this uniqueness and demand that the state protect it from subversion by the West. Civilizational concerns add fuel to geopolitical confrontation, putting a heavy burden on the country’s resources. At times, this results in geopolitical defeats and renewed efforts at Europeanization, such as after the Crimean war of 1853–1856 or during Gorbachev’s Perestroika. The reforms are usually led by the liberal, pro-Western camp. The key problem of the Westernizers, which has not received enough attention in either academic or political debate, is that they tend to pessimistically see themselves as a minority surrounded by uncivilized masses. They claim moral superiority and the right to lead their country to a better future, in which the barbarians will finally be reeducated to fit the supposedly universal standards of the capitalist civilization.

Neither camp trusts in the possibility that people could govern themselves. The inner savages might be noble, but they remain immature, prone to mutiny, incapable of rational political thinking. While conservatives see “the hand of Washington” behind every popular protest, be it in Russia, the post-Soviet countries or in the Arab world, the pro-European Russians are awed by the Kremlin propaganda, which, in their view, is equally skillful in mobilizing politically naïve masses for its own evil purposes.

Contemporary discourse about the native may reproduce the image of the peasant created in the classical Russian literature, starting from the late 18th century sentimentalism. However, in the age of Alexander Radishchev and Alexander Pushkin, the cultural divide was real: The Petrine reforms resulted in the emergence of the new nobility that often felt more at home in Western Europe than in their native Russian village. Subsequent urbanization and the spread of literacy closed this divide. The traditional, peripheral Russia probably survived well into the Soviet time, but was eventually destroyed by collectivization, displacement as well as by universal standardized education and mass culture.

Partly as a reaction to the rise of urbanization, the village prose of the 1970s and 1980s reintroduced the nostalgic picture of the countryside as the locus of the true Russia, where the last remnants of tradition combatted against the seductive influences of urban lifestyle. As a result, the late Soviet society continued to view itself as divided between civilized cosmopolitan urbanites and uncultured but noble peasants, the embodiment of old, traditional Russian values.

This imagery was shared throughout society: Once a conversation moved on from everyday issues and turned to more sublime philosophical or political matters, representing Russia in terms of the grand cultural divide would be as common for agricultural workers and city babushkas as for academics. When the key reference points of the national identity debate are involved, the shared cultural background imbued by school and mass culture is far more important than any impact of elitist cultural consumption, or lack thereof. Paradoxically, the very concern with the inner barbarian reflects the fact that all Russians are taught from the early years to appreciate classical works of literature and art. Education and culture are valued by Russians, and this adds to the perception that one’s ordinary compatriots fall short of the idealized image of a “cultured” person.

The image of the Russian native and the implied cultural divide has survived into the post-Soviet period. This has happened regardless of the fact that for decades, it has remained a discursive construct not rooted in any tangible social reality. Rather, the divide is a way of reaffirming one’s identity by aligning either with or against the imaginary peasant. Politically, however, this practice is far from innocent. It rearticulates the political challenges faced by Russia in terms of a sharp choice between Europeanness and isolationism. Most importantly, focus on this divide pushes aside the concerns and demands of the people from the political agenda, by re-focusing the political debate on the meaning of “civilization” instead.

It is time to admit that Russia’s lack of conformity with the idealized image of Europe, which Russian intellectuals have been polishing for centuries, does not make it less European. Even if it did, it would not matter – not, at least, in any meaningful sense. All that matters is how to make Russia a better place and to give its people a voice in the nation’s politics.

Viatcheslav Morozov is professor of EU-Russia Studies at the University of Tartu. He chairs the Council of the UT Centre for EU-Russia Studies and the Program Committee of the Annual Tartu Conference on Russian and East European Studies. He has published extensively on Russian national identity and foreign policy, and, more recently, Russian domestic affairs. His latest research focuses on how Russia’s political and social development has been conditioned by the country’s position in the international system, an approach laid out in his most recent monograph Russia’s Postcolonial Identity: A Subaltern Empire in a Eurocentric World (Palgrave, 2015). He is a member of the Program on New Approaches to Research and Security in Eurasia (PONARS Eurasia), based at George Washington University.

This article is based on a longer paper “Institutions, Discourses, and Uneven Development: The Material and the Ideational in Russia’s ‘Incomplete’ Europeanization” that he presented at the conference on Regime Evolution, Institutional Change, and Social Transformation in Russia: Lessons for Political Science, April 28, 2018, at Yale University.