Saddam in Custody Offers New Opportunity

Saddam in Custody Offers New Opportunity

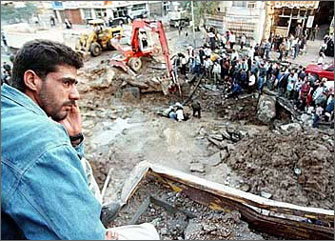

BRUSSELS: European Union governments, even those which were critical of the Iraq war, have been quick to welcome America's capture of former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, hoping the move will speed up the transfer of sovereignty to a transitional Iraqi government and establish conditions for economic and social reconstruction. Europe's satisfaction at seeing Saddam under custody and its newfound goodwill towards the US provides an opportunity to begin mending the transatlantic rift. To do so, however, US President George W. Bush must take quick, decisive action to revise a surprise Pentagon decision excluding European countries that opposed the Iraq conflict from bidding for US-funded reconstruction contracts.

With Saddam facing trial, "I hope we can leave our divisions behind and close the chapter of misunderstanding between the US and Europe," says Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, whose country also holds the current EU presidency. French President Jacques Chirac and Germany's Gerhard Schroeder, who led Europe's anti-Iraq war camp, have also greeted Saddam's arrest as an ideal opportunity for turning the page on violence and terrorism in Iraq.

Events in Baghdad certainly make the task of former Secretary of State James Baker easier than anticipated. The US president's special envoy Baker, who is this week touring key European capitals to try to secure agreement on lightening Iraq's crippling debt burden, did not secure any firm commitments on amounts or deadlines in either Paris or Berlin. He was also interrogated on the Pentagon's move to bar French, German and Russian firms from bidding for $18.6 billion worth of contracts in Iraq. But the new mood was evident even before Baker arrived in Paris. French Foreign Minister Dominique de Villepin told members of the Iraqi Governing Council that creditor countries would probably strike a debt relief deal on Baghdad's $120 billion foreign debt burden in 2004, a decision later confirmed in Chirac's talks with Baker.

Berlin was just as conciliatory, although Schroeder raised the issue of the contracts with Baker, and German Defense Minister Peter Struck warned that Saddam's arrest did not magically dispel differences between the US and Germany. "France, Germany and the United States agree that there should be substantial debt reduction for Iraq in the Paris Club in 2004, and will work closely with each other and with other countries to achieve this objective," the three nations said in a joint statement issued in Berlin, Paris and Washington.

The US has welcomed the first concrete sign of cooperation from two key nations that tried to prevent the war and have refused to contribute troops to the post-war stabilization of the country. But getting Europeans to follow up their promises with real money, know-how, and eventually soldiers for peace-keeping will require replacing what senior EU officials describe as "Pentagon diplomacy" with a more far-sighted and balanced vision of transatlantic cooperation.

The Pentagon move "is not the wisest decision" especially since the US needs European help to ease Iraq's crippling foreign debt and help speed up reconstruction, cautions EU foreign and security policy chief Javier Solana. Europe's financial stake in Iraq is substantial. Baghdad is believed to owe an estimated $3 billion to France, $4.4 billion to Germany, and $8 billion to Russia. EU governments - excluding France and Germany - have collectively promised up to $800 million, including 200 million euros in aid from the European Commission in reconstruction aid for Iraq and French companies, which have old ties to Iraq and intimate knowledge of, for instance, the telephone system, which may prove to be vital in rebuilding the country's infrastructure.

Most Europeans are hoping that American policymakers will see the folly of their ways and recognize that their hard-line stance poses a major threat to efforts to rebuild transatlantic trust and cooperation. Unless the US policy is reversed, fear many in Europe, international divisions over Iraq will resurface, making the process of finding funds for rebuilding the country even more difficult.

EU officials who have been laboring to re-establish normal relations with America following the falling out over Iraq say the Pentagon move has triggered "confusion and incomprehension" in Europe. "We thought we had been fairly successful in patching up ties, finding a new way to work together," says an EU diplomat. "But if the US cannot forget the past and keeps re-opening old wounds, why should anyone else?" Despite initial euphoria following Saddam's capture, European attitudes to Baker's calls for debt forgiveness will be much more skeptical now, warns the diplomat, adding: "The question we're asking is simple: who's running the show in Washington - and what is the US planning to do in Iraq?"

Others in Brussels are also worried that as with its past characterization of 'old' and 'new' Europe, the Pentagon may have triggered another bout of EU in-fighting over Iraq. Britain, which joined the invasion and is a key US ally, has already said Washington is within its rights to take such action. "It's for the Americans to decide how they spend their money. This is American money," British Prime Minister Tony Blair said at an EU summit in Brussels. Another US ally, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, has also stressed it is "logical" that US and its coalition partners should get the prize contracts given that America fought the war.

The US move comes at a time when both Europe and America appeared to be moving beyond feuding over Iraq. Washington decided to scrap its controversial tariffs on imports of foreign steel rather than trigger a trade war with the EU which had threatened retaliatory sanctions worth millions of dollars. EU governments have gone out of their way to head off a showdown with Washington over European defense ambitions by agreeing that their plans to set up an independent military planning cell would be closely coordinated with NATO. EU nations are also carefully considering a request by US Secretary of State Colin Powell that NATO consider an enhanced role in Iraq, possibly as early as next year.

Most importantly, EU governments have spent the last few months trying to put transatlantic relations on a more even keel. In fact, even as many in the bloc denounced the US decision on contracts, leaders from the disparate group of 25 present and future EU states were rallying around a joint declaration which pledged a "constructive, balanced and forward-looking EU partnership" with the United States. "The transatlantic relationship is irreplaceable," said the statement. But unless the US reverses its ban on its erstwhile critics and uses the capture of Saddam to rebuild bridges with Europe, the transatlantic rift is unlikely to be fully mended even by as suave a diplomat as James Baker.

Shada Islam is a Brussels-based journalist specializing in EU trade policy and Europe’s relations with Asia, Africa and the Middle East.