Search for Flavors Influenced Our World

Search for Flavors Influenced Our World

The control over gold, silver, precious metals and recently oil has been a source of conflict and driver of economic globalization. However, other products also inspired exploration, war, conquest and ultimately the emergence of a closely integrated world trading system. One such product awaits in small bottles and packages on the shelves of supermarkets and corner markets: spices.

The quest for spice was one of the earliest drivers of globalization. Long before the voyages of European explorers, spices were globally traded products. As spices once created a global economic network in the Middle Ages, other commodities have followed a similar path. And like spice, many of these products have also faded in popularity. Consider some of the first industries listed on the Dow Jones Industrial Average - leather or rubber for instance - that have since lost their privileged place, replaced by products like Coca-Cola or oil. Spices were prized goods in the Middle Ages. The story of the quest for spices is an early model of globalization, since mirrored by other traded goods.

High prices, a limited supply and mysterious origins fueled a growing effort to discover spices and their source of cultivation. Thus, spices were a global commodity centuries before European voyages. There was a complex chain of relations, yet consumers had little knowledge of producers and vice versa.Desire for spices helped fuel European colonial empires to create political, military and commercial networks under a single power.

Historians know a fair amount about the supply of spices in Europe during the medieval period - the origins, methods of transportation, the prices - but less about demand. Why go to such extraordinary efforts to procure expensive products from exotic lands? Still, demand was great enough to inspire the voyages of Christopher Columbus and Vasco Da Gama, launching the first fateful wave of European colonialism. The desire for aromatic substances has had immense historical repercussions, the effects of which are being felt long after the vogue of spices has diminished.

In a handbook of practical wisdom written by the Florentine merchant Francesco Pegolotti in the early 14th century, some 288 spices are listed, including items like alum, used as a dye fixative. Even so, the variety of imported aromatic substances is astounding and suggests a high demand, including "long pepper" and "grains of Paradise," both peppery in taste but unrelated to black pepper, as well "dragon's blood," a dye and also a drug ingredient.

So, why were spices so highly prized in Europe in the centuries from about 1000 to 1500? One widely disseminated explanation for medieval demand for spices was that they covered the taste of spoiled meat. Spices were more expensive than meat, and fresh meat was available, as suggested by extant records of municipal ordinances prohibiting butchers from throwing unwanted animal parts and blood in the streets. Medieval purchasers consumed meat much fresher than what the average city-dweller in the developed world of today has at hand. However, refrigeration was not available, and some hot spices have been shown to serve as an anti-bacterial agent. Salting, smoking or drying meat were other means of preservation.

Most spices used in cooking began as medical ingredients, and throughout the Middle Ages spices were used as both medicines and condiments. Above all, medieval recipes involve the combination of medical and culinary lore in order to balance food's humeral properties and prevent disease. Most spices were hot and dry and so appropriate in sauces to counteract the moist and wet properties supposedly possessed by most meat and fish. Merchant guilds that supplied spices were variously known as "spicers," "apothecaries," or "pepperers." Inventories and account books of pharmacies show that such culinary stalwarts as pepper, cinnamon and ginger were sold in many varieties and in different medical prescriptions.

More than 100 medieval cookbooks survive today. In the Libre del Coch of Master Robert, written for the king of Naples, are about 200 recipes, 154 of which call for sugar, 125 require cinnamon, 76 ginger, and 54 saffron. Spices ordered for the wedding of George "the Rich," Duke of Bavaria, and Jadwiga of Poland in 1475 included 386 pounds of pepper, 286 pounds of ginger, 257 pounds of saffron, 205 pounds of cinnamon, pounds of cloves, and 85 pounds of nutmeg. Clearly, recipes from the era called for not only large quantities of spices, but also a great variety. Spices such as cinnamon or nutmeg associated with desserts were used in meat and fish dishes. Sugar functioned as a spice during the era. Styles in cooking change, and given the modern preference for spicy dishes, we can appreciate the medieval culinary aesthethic that emphasized color, ingenuity and a high degree of processing. Far from the idea of simply grilling meat, medieval food required chopping, molding, simmering and various steps including sauces or aspic.

The demand for spices may then be said to combine a taste for strongly flavored food, a belief in their medicinal properties, and also the sense of well-being, refinement and health the fragrance was said to confer, similar to the claims made by those practicing aromatherapy in recent years. Once these varied properties were recognized or accepted, spices became objects of conspicuous consumption, a mark of elite status as well as markers of exquisite taste in all senses of the word.

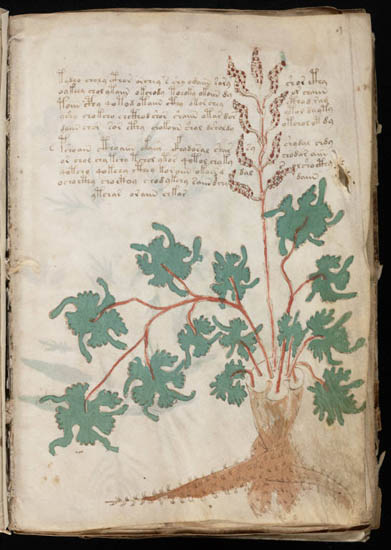

Where spices came from was known in a vague sense centuries before the voyages of Columbus. Just how vague may be judged by looking at medieval world maps that attempt to incorporate information about Asia from the Book of Genesis, legends of the conquests of Alexander, Christian prophetic literature, especially regarding the apocalypse, and real and fabricated travel accounts such as those of Marco Polo and John Mandeville.

To the medieval European imagination, the East was exotic and alluring. Medieval maps often placed India close to the so-called Earthly Paradise, the Garden of Eden described in the Bible.

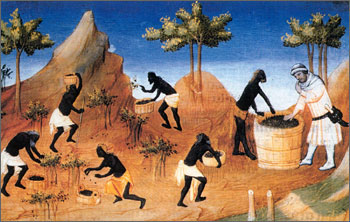

Geographical knowledge has a lot to do with the perceptions of spices’ relative scarcity and the reasons for their high prices. An example of the varying notions of scarcity is the conflicting information about how pepper is harvested. As far back as the 7th century Europeans thought that pepper in India grew on trees "guarded" by serpents that would bite and poison anyone who attempted to gather the fruit. The only way to harvest pepper was to burn the trees, which would drive the snakes underground. Of course, this bit of lore would explain the shriveled black peppercorns, but not white, pink or other colors.

Certain writers occasionally questioned how pepper could be collected year after year since the fire would presumably destroy the entire tree. Only with a report by the merchant Nicolo de' Conti in the early 15th century do we have a European eyewitness at a pepper harvest on the Malabar Coast. Nicolo remarks that there are no snakes, no fire, no bizarre harvesting methods. Nicolo's account almost invites merchants to undermine a price differential resulting from artificial barriers, middlemen and ignorance, and encourages exploration and economic opportunity.

Price and availability of spices in Europe were affected by global factors: from the weather in India to relations between Christian and Muslim powers. While the papacy and the Kingdom of Cyprus attempted to restart the Crusades by prohibiting trade with Egypt, the Venetians and Genoese fought to control that lucrative trade. Traders throughout the Mediterranean bought spices in Alexandria, Beirut and sometimes ports on the eastern Mediterranean or the Black Sea.

Spices never had the enduring allure or power of gold and silver or the commercial potential of new products such as tobacco, indigo or sugar. But the taste for spices did continue for a while beyond the Middle Ages. As late as the 17th century, the English and the Dutch were struggling for control of the Spice Islands: Dutch New Amsterdam, or New York, was exchanged by the British for one of the Moluccan Islands where nutmeg was grown. Spices faded from European cuisine not only because of changing tastes, but also because ancient medical ideas lost currency, more exciting drugs arrived from the New World, and the prevalence of opiates rose. Nonetheless, spices' eclipse in later centuries should not obscure their role as the basis for the first large-scale global economic network and the force behind the first expansion of Europe.

Paul Freedman is professor of history at Yale University.

Comments

1. What were spices used for during the Middle Ages? List and describe at least 3 uses.

2. What did most Europeans know about the area where spices came from?

3. What affected the price and availability of spices?

4. How has the desire for spices affected world history?

I am teaching a unit on herbs and spices and this will be a great addition to my unit.

Very helpful for our world history unit. Great image on pepper gathering for discussion as well.