The Slow US Withdrawal From Afghanistan

The Slow US Withdrawal From Afghanistan

RABAT: Negotiations for a political settlement between the Taliban and the United States to end the war in Afghanistan, a once-promising process, all but collapsed in early September. Many analysts have mulled over what the conclusion of the longest foreign military engagement in American history might have meant for the War on Terror. A question of equal importance: How would these developments affect the War on Drugs?

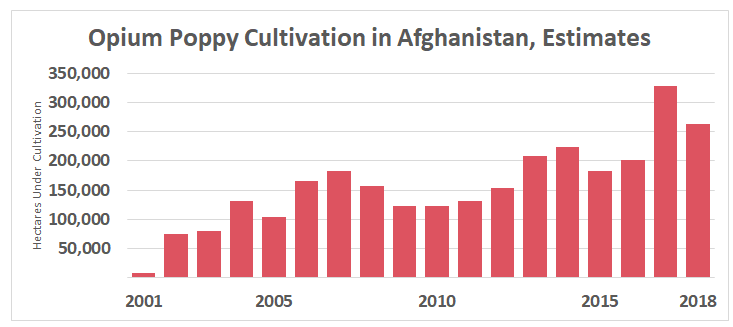

Afghanistan supplies 90 percent of the world’s opium and 95 percent of Europe’s. The Taliban earns as much as $400 million every year from its own role in the illegal drug trade. Though the United States dedicated an impressive array of resources to combating narco-trafficking at the height of the War in Afghanistan, an American withdrawal from the Central Asian country could mark the end of any American role in the Afghan arena of the War on Drugs. For their part, the Taliban and other Afghan militants, earning millions, have little incentive to fight the illegal drug trade. If the United States wants to keep narco-trafficking from ballooning as soon as its soldiers leave Afghanistan, its diplomats must address this problem with the Taliban.

Before the United States launched peace talks with the Taliban, American policymakers viewed tackling the illegal drug trade in Afghanistan as a method of weakening the insurgents. The United States deployed more than 100 employees of the Drug Enforcement Administration, or DEA, to Afghanistan. In turn, the DEA organized strike forces of special agents, dubbed “FAST teams,” to raid Afghan drug labs and opium dens. The DEA also partnered with the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement, or INL, part of the State Department, to train two Afghan law enforcement agencies dedicated to counternarcotics: the Sensitive and Technical Investigative Units, overseen by the Afghan Counternarcotics Ministry. This collaboration led to several high-profile successes for the DEA, among them the capture of the Taliban-linked narco-traffickers Haji Bagcho and Khan Mohammad. By 2018, a year before the outset of peace talks between the Taliban and the United States in Doha, the United States had spent $8.7 billion on its Afghan counternarcotics campaign.

In the rush to conclude a peace treaty with the Taliban, the Trump administration appeared to abandon its bid to curb the illegal drug trade in Afghanistan. While American generals announced a new strategy of employing Afghan and US warplanes to destroy Taliban drug labs to much fanfare in November 2017, the United States canceled the program in February 2019. Peace talks between American diplomats and Taliban negotiators began the same month. The decline of the US commitment to counternarcotics in Afghanistan started far earlier, however. In 2011, when President Barack Obama was first eyeing an American withdrawal from the Central Asian country, the number of DEA employees in Afghanistan had shrunk to around 75, split between the strategic cities of Herat, Jalalabad, Kandahar and Kunduz. In 2016, meanwhile, the Defense Department stopped updating Congress on counternarcotics efforts in Afghanistan. In what could have the greatest consequences for the future of Afghan participation in the War on Drugs, an American government agency that studies the U.S.’s war effort, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, reported this year, “Afghanistan’s Ministry of Counter Narcotics will likely be disbanded, according to the State Department.”

The United States also cut $100 million in funding and suspended another $60 million just a week before Afghanistan’s September 28 presidential election. Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asia, Alice Wells, advised the House Foreign Affairs Committee that the administration of US President Donald Trump had profound concerns about “corruption, government malfeasance, record-high opium production, and criminalization of the economy.” While no one knows the winner of Afghanistan’s election for the time being, counternarcotics seemed far from the minds of all top candidates, and analysts have yet to assess what role the suspension of some US funding to Afghanistan played in the results. So far, no other country seems to have followed the US example.

Like the War on Terror, the War on Drugs achieved limited results in Afghanistan. Still, the United States and its Afghan partners have an obvious interest in preventing the Central Asian country from descending into lawlessness and turning into a greater hotbed of narco-trafficking. When the United State departs Afghanistan, a possibility that seems no less likely with the implosion of peace talks, a larger share of responsibility for law enforcement in Afghanistan will fall to the Afghan authorities, who will have little choice but to compromise with the Taliban in the name of any peace treaty. If Afghan and US diplomats choose to revive the peace process and include a discussion of the insurgents’ role in the illegal drug, the United States may even find an opportunity to salvage what remains of its counternarcotics campaign and undermine narco-trafficking in Afghanistan.

The Taliban could prove willing to surrender its involvement in the illegal drug trade if the United States decides to return to the negotiating table in addition to offering enough concessions. As much as the insurgents profit from narco-trafficking today, they once enforced the only successful ban on the illegal drug trade in the history of Afghanistan. In 2000, when the Taliban governed most of the Central Asian country as the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, the DEA judged that a onetime Taliban attempt to outlaw opium’s cultivation had succeeded where two decades of American counternarcotics programs would fail. The contemporary extent of the Taliban’s participation in the illegal drug trade notwithstanding, the insurgents’ past ban on narco-trafficking indicates that they could come around to Afghan and US policymakers’ counternarcotics objectives.

During negotiations with the Taliban about the likely schedule for an American withdrawal from Afghanistan, US diplomats proposed that the the country could leave a task force of commandos in the Central Asian country to pursue Al Qaeda and requested a binding pledge from the Taliban that terrorist groups would never again use Afghanistan as a launch pad for anti-US attacks. A similar arrangement might guarantee the future of Afghan-American counternarcotics efforts. The United States could push the Taliban to allow a skeleton crew of DEA special agents and INL experts to stay in Afghanistan as advisors to their Afghan counterparts, and American negotiators could also ask that the Taliban reenact its ban on the illegal drug trade. Only negotiations could decide what the United States would have to promise in return, but the Taliban would likely demand that the United States provide an alternative source of income for Taliban warlords reliant on narco-trafficking. Viable alternatives might include providing former members of the Taliban well-paid positions in the Afghan government and training them to run profitable legal businesses.

No matter the urgency of limiting further bloodshed in Afghanistan, the United States must remember the havoc wrought by the illegal drug trade in the Central Asian country. Peace talks presented one of the best chances in years for the United States to realize its counternarcotics goals in Afghanistan. With the apparent failure of the peace process, American diplomats have turned their attention to Iran, North Korea and other headline-grabbing adversaries. Unless the United States moves to reinvest itself in the Afghan front of the War on Drugs, Afghan and American officials will likely be dealing with the consequences of the illegal drug trade in Afghanistan for decades to come.

Austin Bodetti studies the intersection of Islam, culture and politics in Africa and Asia. His research has appeared in The Daily Beast, USA Today, Vox, and Wired.