Stock Market Hiccups No Cause for Worry

Stock Market Hiccups No Cause for Worry

Enlarge image

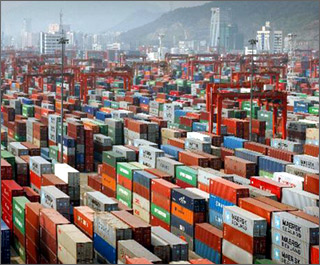

SINGAPORE: Recent ructions in Asian financial markets and deepening US anxiety over its ballooning trade and budget deficits have raised concerns about global economic health. However, economists are hopeful that, while in the short term, economic growth in Asia may slow as a result of global economic deceleration and protectionist measures, it will not detract from the long-term prospects. The great engines of growth, China and India, will continue to expand with positive implications for the global economy.

For sure, a cyclical slowdown in the US is adding to the short-term difficulties in countries such as China and India where ultra-strong growth has created either some degree of overheating or imbalances which require policies to be tightened.

India has seen inflation soar and external balances weaken sharply, forcing its central bank to tighten more aggressively. China is worried by signs of excessive investment and uncontrolled asset inflation in some areas, so it too is trying to slow its economy. In the short term, then, both China and India could lose momentum as interest rates rise and as their central banks impose a range of administrative restrictions to curtail loan growth and demand. However, the forces that are promoting strong growth in both these countries for the long term are still at work and the slowdown will be short-lived.

What are these long-term growth-promoting forces that are so powerful? The most important is the mental revolution that has unleashed entrepreneurial energies in both Asian giants. First, in China in the 1980s and more recently in India since the 1990s, people long satisfied with slow growth and an economy driven by state initiative have realized that the old statist restrictions are disappearing and that the sky is the limit in terms of how much wealth they can create for themselves. What seemed impossible to achieve is now seen as very much within reach. A can-do spirit, combined with the success of the first wave of billionaires, spurs a whole new generation of entrepreneurs.

So, businesses are being formed at an unprecedented rate, mobilizing rapidly rising savings to be channelled into building productive capacity that generates jobs, incomes and huge new wealth. India has seen its savings rate, which used to be stuck below 20 percent for decades, soar to above 30 percent now, with the investment rate also rising sharply to around 33 percent. China’s investment rate of above 40 percent is a world record. The productive capacity being built today will underpin economic growth for some time to come.

Once the mental revolution is underway, growth begets more growth. As incomes grow and as the economy becomes more complex, new business opportunities emerge – whether it is more sophisticated support services in finance and logistics or higher value consumer spending. This creates new industries with more jobs, exactly what is happening in China and India. China’s savings industry has grown – from an overwhelming dependence on bank deposits into a huge sector complete with mutual funds, pension funds, advisory services, brokerages and research activities. In India, a new area of substantial growth in coming years will be a new supply chain from farmers to retail outlets as India’s super-ambitious entrepreneurs build modern retail networks for the first time. This will create whole new industries – a cold chain from farm to town, transportation services, hyper-markets and the like.

Then, the challenge to maintaining the momentum of growth is to get the regulatory framework, infrastructure and other basics, such as education, application of technology and so on, right. China has created new regulatory institutions in many areas – banking, securities, telecommunications and so on. Since the early 1990s, India has impressed with new institutions in similar areas such as the Securities Exchange Board of India while its central bank has cleaned up the banking sector.

Infrastructure has been a problem in India but not in China. China has been farsighted in planning roads, railways, airports, ports, mass transit, power stations and urban-support systems ahead of need. In the next few years, India will see a dramatic transformation of its airports and national highway system. While infrastructure constraints will remain a bugbear for Indian businesses for a while, they will become less of a drag on growth as time progresses. Similarly, both countries are putting in place expanded education systems to generate the right kinds of workers and professionals for the future.

Finally, both countries still have vastly underexploited areas of growth that are likely to be tapped in coming years. India, for instance, received only 4.4 million tourists in 2006. Despite its rich treasure trove of historic monuments, beaches, mountains and cultural events, India attracts a fraction of the tourists that smaller places such as Hong Kong or Singapore receive. But tourist arrivals have doubled in the last 10 years and are likely to continue surging as better marketing and more air services link the country to the rest of the world. Despite its recent huge growth, China’s finance sector is still a pygmy and the sector is set to grow by multiples in coming years.

This unprecedented simultaneous growth in two of the world’s largest countries will boost demand in the global economy and open up massive market opportunities for trading partners, especially neighboring Asian economies. Moreover, the rest of Asia is also being energized by the boom in China and India. Southeast Asia, which has suffered relatively low growth since the 1997 financial crisis appears, ready to put those difficult years of adjustment behind – there are signs of an upward shift in investment which will drive growth to a higher level of 7 to 8 percent rather than the 4 to 6 percent we have seen in recent years.

Given the powerful forces at work, it would take a massive shock to derail Asia’s growth and the positive impact it will have on the rest of the world. Politics is, of course, one risk. So far, India’s democracy with all its flaws has adapted well to its new high-growth mode. But the fact is that corruption, terrorism by religious and leftist extremists, separatism and inter-religious rivalries continue to beset India. Its relations with its neighbors, including nuclear-armed Pakistan, continue to be fraught despite some recent improvement.

China has been slow to open up its political system to accommodate the new business and middle classes, or to adjust to a more open system where so many foreign influences are changing the way people think. Nevertheless, China’s communist party has allowed some changes such as limited elections at grassroots levels and more personal freedoms. The key to political stability in the long term is the creation of social and political institutions which are strong and outlive personalities. Since the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, China has made huge strides in developing such institutions, and its political system clearly does not depend on the power of a single dominant leader as it did during Mao’s rule and that of Deng Xiaoping, who died 10 years ago.

So, although the risk of a political cataclysm so great as to derail growth is low, it cannot be entirely discounted. Otherwise, there is every reason to expect high growth to continue in Asia, with occasional bumps along the way.

Based in Singapore, Manu Bhaskaran is a partner with the Centennial Group, heading economic research practice.