Syrian Conflict Promises Toxic Outcome – Part II

Syrian Conflict Promises Toxic Outcome – Part II

LONDON: There’s no satisfying solution to the 16-month old Syrian bloodshed. To let Syrian President Bashar al-Assad crush popular demand for genuine political reform through brutal force, with support from Moscow and Beijing, would strengthen the hands of Russia and Iran.

Saudi Arabian and Qatari weaponry, supplied to Sunni militants through Turkey, risks sectarian bloodbath not only in Syria but in Lebanon and Iraq as well as Bahrain and the Saudi kingdom’s Eastern Province, paving the way for Al Qaeda affiliates such as the Farouq Brigade to benefit from the power vacuum following Assad’s downfall.

The inherent weakness of Syria’s present political order is obvious: Whereas the population is 70 percent Sunni, its military, police and intelligence services are led mainly by Alawis, a Shia sub-sect, as is the ruling Arab Baath Socialist Party. Such disjunction also exists in Bahrain – a tiny group of islands in the Gulf with the main island linked by a causeway to predominantly Sunni Saudi Arabia – with the roles reversed.

The Shia factor underwrites the alliance Syria has forged with predominantly Shia Iran, since the latter’s establishment of an Islamic republic, and Hezbollah in Lebanon, founded in 1982 with assistance of the Iranian ambassador in Damascus.

Around the hard core of the Alawi support for the Assad regime are the Christians, 10 percent, and equally numerous Ismailis, Druzes and ethnic Kurds, who collectively fear the onset of a post-Assad regime dominated by militant Sunnis. According to the Vatican news agency Fides, Sunni fighters recently went from house to house in the Hamidiya and Bustan al-Diwan neighborhoods of Homs under their control, forcing Christians to flee. All told, 50,000 Christians have lost their homes in Homs, some by army shelling, but many more because of ongoing targeted assaults by Sunni extremists such as the Farouq Brigade, composed mainly of foreign jihadists who have poured into Syria.

Among Syria’s immediate neighbors, Turkey has emerged as a leading opponent of the Assad regime for two reasons, one aired publicly and the other unspoken. As leaders of the governing Justice and Development Party in a secular, democratic Turkey, President Abdullah Gul and Prime Minister Tayyip Erdoğan were genuinely horrified by the Syrian Army’s use of heavy weapons against civilian targets.

Left unmentioned so far is the low esteem in which the Turkish government and political establishment hold their own Alevi minority. Turkey’s Alevis, akin to the Alawis in Syria, form up to 15 percent of the population, and are victims of widespread discrimination.

It’s therefore not surprising that Turkish leaders have allied with Saudi Arabia’s and Qatar’s Sunni rulers. Indeed the al Saud and al Thani ruling families belong to the ultra-orthodox puritanical Wahhabi sub-sect within Sunni Islam, founded by Muhammad bin Abdul Wahhab (1703-87) in central Arabia. In 1802 Wahhabi warriors attacked the shrine of Imam Hussein, martyred son of Imam Ali, founder of Shia Islam, in Karbala. Since then Wahhabi preachers have continued to regard Shias as almost heretical.

Wahhabis’ enmity toward Shias reemerged with the rise of Iran run by Shia mullahs since 1979. With increasing alarm, the Wahhabi House of Saud watched Iran extend its influence into the Arab world – in Syria and Lebanon, among the Palestinians through Hamas, topped by the emergence of a Shia-dominated government in Iraq, thanks to US military intervention against Sunni Saddam Hussein.

Underscoring the anti-Assad alliance of Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey is the Sunni affiliation and a shared aim to frustrate Iran’s ambition to become the hegemonic power in the Persian Gulf region and end that influence in Syria and Lebanon. Their strategic goal coincides with Israel’s.

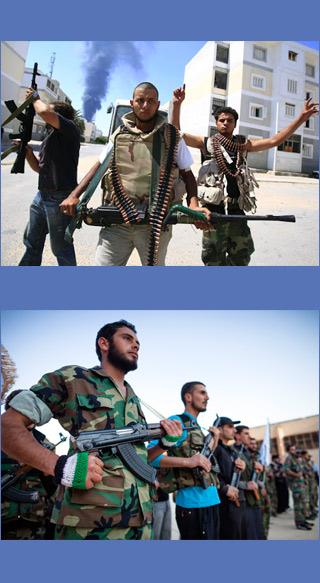

The Saudi and Qatari weapons shipped to Turkey are being smuggled into Syria to arm the rebel Free Syrian Army. FSA. by a center in Istanbul, controlled by the Turkish intelligence agency and manned by exiled Syrians, who coordinate supply lines into northern Syria, with US Central Intelligence Agency officials deciding which rebel group gets which weapons. The FSA is a loose conglomeration of military defectors, armed volunteers and Al Qaeda operatives from several Arab countries.

Whereas internal sectarian and external geopolitical elements have combined to propel Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey to boost the armed rebellion against the Assad regime, the focus of the US and Israeli policymakers is geopolitical – to delink Iran from Syria, depriving it of the Mediterranean flank next to Israel, and divest Russia of its Mediterranean naval presence, narrowed down to the Syrian port of Tartus since the fall of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya last year.

The primary driving force in the anti-Assad camp is Sunni hostility toward Alawis/ Shias. The success in overthrowing the status quo in Syria can only be achieved by inflaming Sunni-Shia relations. This is tantamount to playing with fire, because the sectarian fault line extends beyond the oil-rich Middle East, well into Afghanistan and Pakistan.

In Iraq, Sunni-Shia relations deteriorated to a low-intensity civil war in 2006-2007 and remain strained. On 13 June concerted suicide attacks on Shia gatherings in Baghdad and elsewhere killed 72 people. In Lebanon, pro-Riyadh Sunnis and pro-Tehran Shias coexist uneasily. In Bahrain, the Shia majority has protested against the Sunni al Khalifa ruling family off and on since 1994.

Saudi Arabia is vulnerable. Most of its Shias, 15 percent of the population, are concentrated in its oil-bearing Eastern Province, where they’re an integral part of the petroleum industry. In March 2011, defying warnings by authorities, Shias in the province’s major city of Qatif demonstrated, shouting: “One people, not two – the people of Qatif and Bahrain.” In oil-rich Kuwait, Shias are 30 percent of the indigenous population. Sabotage of the Saudi or Kuwaiti oil industry by local Shias, facing a Sunni onslaught, would have global repercussions.

This factor weighs heavily with the policymakers of China, dependent on Middle East oil supplies. In collaboration with the Kremlin, the Chinese have consistently opposed any move, covert or overt, by Western powers at the UN Security Council to bring about regime change in Damascus. The Beijing-Moscow stance is in line with a common aim to create and sustain a multipolar globe on the ashes of a unipolar world dominated by Washington.

Such global visions do not inform FSA commanders, who routinely foreswear any sectarian bias. Yet the FSA consists almost entirely of Sunnis, many followers of the clandestine, deeply rooted, anti-Shia Muslim Brotherhood. Most FSA units are named after historical Sunni warriors who battled Shias.

Al Qaeda leader Ayman Zawahiri called on Muslims in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey and elsewhere to join the fight against “the pernicious, cancerous regime” of Assad last February – and many militant jihadists heeded the call.

Terrorist attacks on the Syrian government’s targets have been claimed by Jabhat al-Nusra li Ahl Ash-Sham, or Support Front for the People of Syria, an Al Qaeda affiliate. Farouq Brigade, composed mainly of Al Qaeda operatives, is an openly recognized part of the FSA, and performing better than other FSA units.

Regrettably, leaders in Washington, Ankara, Riyadh and Doha have either failed to ponder the probable consequences of the overthrow of Assad or feel unduly confident of managing them: a bloody civil war destabilizing the region, at worst; the post-Assad regime inheriting a fractured country where Al Qaeda militants have free rein, at best; and an inevitable spike in oil prices for a world in the midst of the longest recession since the 1930s Great Depression.

Dilip Hiro’s most recent book is “Apocalyptic Realm: Jihadists in South Asia,” published in April by Yale University Press, New Haven and London. Click here to read an excerpt.