Syrian Massacres: World Has No Appetite for Intervention

Syrian Massacres: World Has No Appetite for Intervention

WASHINGTON: For 10 months, the world has watched in horror as Bashar al Assad’s regime carries out regular massacres against unarmed civilians across Syria in a bid to quell the unrest gripping the country. No doubt inspired by the successes of their Arab brethren elsewhere, thousands of Syrians have staged protests asking that their rights and dignity be respected. Although the Syrian government has vacillated between intensifying its crackdown and feigning interest in meeting some demands of its people, it’s clear that Assad is not likely to follow the example of Egypt’s Mubarak or Tunisia’s Ben Ali by stepping down.

As the violence continues, the international community might have no choice but to usher Assad out, as was done with Libya’s Gaddafi. Otherwise, Al Qaeda could come back from the precipice.

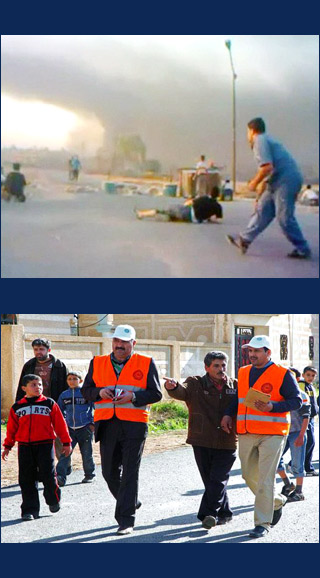

Two massive suicide bombings that exploded near government security buildings in Damascus on 23 December and a similar attack on 6 January raised more than a few eyebrows. Almost instantly the Syrian government attributed the carnage to Al Qaeda. Just as quickly, opposition figures questioned the claims, accusing the government of orchestrating the bombings, a pretext for cracking down on protesters trying to bring another chapter in the Arab Spring to a successful conclusion. Making matters murkier was the fact that the attacks coincided with the arrival of Arab League observers assessing whether the Syrian regime is adhering to a league-sponsored plan to end the violence.

Weeks later, no group, including Al Qaeda, has taken credit for the operations that left scores of Syrians dead.

Syria has long had ties to militant groups including Hezbollah, Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad. Only a few years ago many thought of Syria as a main conduit through which foreign Sunni militants were entering Iraq. Whether Al Qaeda has established a foothold in Syria may not be clear for some time, and in some ways, it is immaterial.

Unless the international community takes a more proactive role in stopping the violence, the prospects of Syria becoming a new destination and haven for foreign jihadists – rivaling Afghanistan in the 1980s or Iraq after 2003 – are real.

A combination of brutality, arrogance and short-sightedness by Assad’s regime has furnished Al Qaeda with a treasure-trove of readymade recruitment material which could potentially galvanize militants across the Muslim world. Equally as important, the Syria narrative may also resonate with moderate Muslims who will find it difficult to criticize Al Qaeda’s attacks if they target the regime exclusively. Sunni-majority nations, a number of which have strongly condemned the Syrian regimes’ repression, may not try to stop such an outflow.

Videos of Assad’s thugs – known across the Arab world as Shabiha – have been posted on the internet. At least one shows a man, ostensibly a Sunni, being forced to say “there is no God but Bashar,” and thousands of youths in Arabic chat rooms have responded to express revulsion and sympathy.

Those same bloggers also expressed contempt for Muammar Gaddafi during the revolution last year, yet those emotions were tempered by the Libyan ruler’s reputation as a raving lunatic. People throughout the region do not regard Assad as crazy, and the hatred directed at him personally is almost unprecedented. Most importantly, the violence in Libya was not refracted through a religious prism. Libya is 97 percent Sunni Muslims; both Gaddafi and the Libyan rebels were Sunni. That is not the case in Syria, where the regime is Alawi, a branch of Shia, ruling over a population that is 70 percent Sunni.

Recent reports indicate that some Iraqi Sunni militants have called on cohorts to join the jihad in Syria. The death of a Saudi who took part in a protest was well publicized. It won’t be difficult for Al Qaeda or other militant groups to exploit the perception among many that the devastation befalling Sunni Muslims is being perpetrated mostly by Alawites, Druze and Christians.

One must remember that hundreds of Arab men left everything behind and traveled to Afghanistan to fight a conflict billed as the ultimate jihad in the 1980s. Likewise in Iraq, Arabs from Sunni-majority nations went to fight the Americans and their Shia Safavid allies who were also portrayed as conspiring against Sunnis. In both these conflicts, however, foreign militants were motivated by narratives that were not corroborated nearly to the same extent as Syria’s will continue to be. Hours of amateur footage documenting Al Shabiha’s brutality could make Al Qaeda’s pitch an easy sell.

Al Qaeda gained traction by pointing to the Russians in Afghanistan as a faceless symbol of godless communism. Even in Iraq, no single Shia figure was widely reviled – although of late Nouri al Maliki has become a polarizing figure.

Assad, though, is a target of Arab ire, with scores of participants on internet forums daily wishing him a “Gaddafi ending.” Detractors rarely refer to him by either his first or last name, and many simply call him “Al Taghiya,” the Tyrant.

Formation of an international consensus on proceeding in Syria has proven elusive. While Western nations, including the US , France and Britain, seem to be losing patience with Assad’s continuing brutality and intransigence, others, especially Russia and China, also permanent members of the UN Security Council, have expressed strong reservations about any UN-sanctioned international intervention, including economic sanctions or military action.

Although the Arab League has taken unprecedented initiatives against Assad’s regime – suspending Syria’s membership from the regional body and imposing economic sanctions which could potentially adversely affect the Syrian economy, especially over the long-term – the abstention of Iraq and Lebanon from the vote on the sanctions has highlighted the lack of a unified approach among Arab nations as well.

Nevertheless, if the carnage continues – and most indicators suggest it will – reluctant countries may have to come to terms with two realities:

The first is that Assad’s brutal crackdown has made it virtually impossible for his regime to ever be considered a respectable member of the international community. Any future dealings with him will come at great political cost.

Second, Assad’s survival, especially when juxtaposed with Mubarak’s or Ben Ali’s ousters – both of whom offered much more tepid reactions to their own protestors – will strike many around the Arab world as patently unjust, particularly among Syrians themselves.

Al Qaeda and other militant groups will spare no effort to harness this sense of injustice to the fullest.

If the international community does not take a firm stand now, it could find itself having to choose between supporting a brutal regime that has killed thousands of its own people or allowing Al Qaeda to turn Syria into a staging ground where it could recover from massive losses suffered in recent years but also potentially create a new generation of militants. At the very least, Syria could reinforce Al Qaeda’s narrative – which maintains that Muslims the world over are under siege – giving it a much needed boost, at a time when the terrorist group is desperate to regain its footing.

Fahad Nazer is a terrorism analyst based in Washington, DC.