Tension Highlights North Korea’s Limitations

Tension Highlights North Korea’s Limitations

SEOUL: The blood-curdling threats against the South emanating from North Korea are all too familiar, but ironically the repeat performance only underlines the North’s weakness. A changing global landscape for the Koreas, especially weakening Chinese support for Pyongyang, is making the North Korean threat increasingly hollow.

On August 20 North Korea declared a “quasi state of war” following the exchange of artillery shells across the misnamed Demilitarized Zone, once again raising the specter of conflict on the Korean Peninsula.

Yet instead of waging war, Pyongyang, chastened perhaps by Chinese counsel for restraint, began talks with Seoul and agreed to call off its state of war and start dialogue with the South.

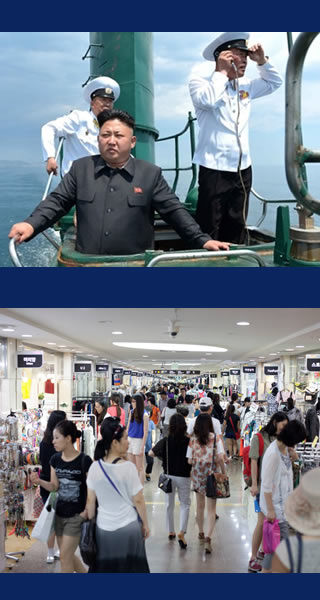

For more than half a century since the signing of the 1953 armistice agreement, the capitalist-based, democratic South has had to cope with an endless series of armed provocations from the aggressive, totalitarian system of the North. But the end of the Cold War in 1991 brought increasingly closer relations between US-backed South Korea and China and Russia allied with the north. Today, North Korea confronts dramatically new international dynamics as it seeks to alter the status quo. The strong-arm tactics by Kim Jong Un, the 33-year-old hereditary leader who came to power in December 2011, to gain political concessions simply are not working.

The current crisis erupted August 8 when a landmine secretly placed by the North underneath the line dividing the two sides exploded, seriously wounding two South Korean patrol guards. Pyongyang’s refusal to take responsibility for this case of armistice violation prompted Seoul to respond with loudspeakers installed along the demarcation line, about 255-kilometers long, which had been silenced by agreement during the past 11 years. The loudspeakers blast news of the outside world, including human rights violations in the North, to North Korean troops on the other side of the line. The news blasts, which prompt a few North Korean soldiers to defect each year, are powerful enough to reach North Korean civilians within 25 kilometers.

North Korean defectors in the South also occasionally launch balloons carrying propaganda leaflets across the line. Such psychological warfare has been a source of great irritation, undermining grassroots-level loyalty to the regime. Uncensored news about the outside world encourages civilians as well as those in uniform to defect.

Shortly after midnight Tuesday, North and South negotiators at Panmunjom agreed on a joint statement. The blasts caused so much concern for the North that the government expressed “regrets” over the landmine incident in exchange for the South’s promise to silence the loudspeakers. The statement’s wording indicates that the South will resume the broadcasts if the North commits fresh provocations. The North also agreed to call off its declaration of the semi-state of war and restart the peace process including a reunion for families divided by the war that began in 1950.

South Korea has won this round of confrontation, but that does not end its serious concern over the North’s use of hit-and-run guerrilla style attacks designed to wear down the South. Since signing of the armistice agreement in 1953, the North has committed some 2,000 cases of such provocations, half taking place along the armistice border. These include infiltration of individual saboteurs, group incursions, firing across the line, or planting of landmines inside the southern border.

One such provocation in 1976, the ax murder of two US Army officers inside the neutral area of Panmunjom, nearly triggered full-scale war. That incident so outraged the US Command that President Gerald Ford ordered B-52 bombers and the USS Midway to the Korea Peninsula in a move to punish the attack. In the face of a massive show of force, North Korean leader Kim Il Sung backed down and issued his first statement of apology.

His grandson Kim Jong Un, the North’s new leader, is focusing on the Yellow Sea zone, where he is probing to neutralize the US-imposed Northern Limit Line, serving as an effective maritime border between the two sides. Two naval clashes flared there in 1999 and 2002, but the most spectacular attack occurred in 2010 when the North launched a submarine torpedo attack on the battleship Cheonan inside the South’s territorial waters, killing 45 seamen.

The sinking of the Cheonan was a wakeup call for Seoul. Since then, no amount of North Korean saber-rattling or its trademark brinkmanship appears likely to move Seoul’s determination to dispense with the recurring tension. Although Radio Pyongyang declared that North Korean combat-ready troops were being massed close to the border, average citizens go about their daily routines. To provoke a panic in the South, the North also let it be known that 50 of its 70 submarines left port. Kim’s implicit message: Stop the loudspeakers or he would start a war.

Analysts have pondered what may happen after South Korea called Kim’s bluff. For the most part, analysts anticipate the regime to resume peaceful contacts, especially since the North’s economy is in a bad shape, including a recent drought that promises food shortages. North Korea continues to rely on China for half its food needs.

In the long run, economic hardships and continuous rounds of executions and purges raise questions about the stability of Kim’s leadership. A case in point is the bad timing for stirring tensions while the US–South Korean annual military exercise, Ulchi Freedom Guardian, is underway. US and South Korean air force fighter jets are flying sorties over bombing practices along the border. “The North understands it risks annihilation if it starts another war,” said Hong Hyun Ik, a leading North Korea watcher for authoritative Sejong Institute in Seoul, during a television roundtable. “What Kim is saying is that ‘Don’t undermine my position with loudspeakers. Don’t embarrass me with UN resolutions on human rights violations…leave me in peace.’”

Compounding Kim’s problems is a deficiency of sympathy from China, his closest neighbor and economic lifeline. Beijing has informally told Pyongyang that it should lower its war fever and “exercise restraint.” China’s foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chinying called for calm on both sides, but her message was more painful for Kim. China is in the midst of an economic slowdown and wants to prevent any border conflict that would threaten regional stability.

Lest Kim misses this message, China is reportedly deploying troops along the border with the North in a pointed show of force – amounting to more than a gentle arm-twisting as Beijing prepares for the September 3 World War Two Victory March with President Park as guest on the podium. Her presence should be doubly goring for Kim, whose regime claims legitimacy in Kim Il Sung’s war against Japan in China.

Kim’s friends in Moscow, as those in China, have similarly advised calm, asking for “restraint on both sides,” a calculated expression of neutrality. Russian President Vladimir Putin is more interested in selling oil and gas to South Korea than supporting Kim’s adventurous course.

The political and military dynamics surrounding the Korean Peninsula have transformed, limiting North Korea’s space to disrupt the current balance of power. Kim faces a sobering choice: Either he should call for peace and focus on the economic well-being of his nation, or risk facing a catastrophic end to his regime.

Shim Jae Hoon is a Seoul-based journalist.