Terrorism Undermines Political Islam in Indonesia

Terrorism Undermines Political Islam in Indonesia

CAMBRIDGE, USA: Indonesia's major Islamist political parties have found themselves in a difficult position ever since terrorism hit the nation's shores. Fighting from a significant but minority position, political parties wishing to bring about an Islamic republic in Indonesia know that they must unite if they are to pose any serious challenge to the secular forces that dominate the country's political scene.

With terrorism becoming a serious threat to Indonesia, home to the world's largest Muslim population, Islamist political parties are facing a dilemma. In the face of rising anti-terrorist sentiment, the marriage of convenience between the majority mainstream democratic factions and smaller radical factions is now under a lot of strain. To retain any legitimacy in the eyes of potential voters, the parties' leaders are under pressure to publicly renounce their association with radical groups that have exploited religious symbols for political goals.

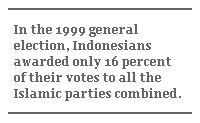

This is putting Islamist parties in a bind. Cutting their loose ties with radical Islamist groups would cost Islamist parties some of their traditional support in the April 2004 election. No matter how small that support has been, it has been crucial in their bids to gain a foothold in Indonesia's new democracy. In the 1999 general election, Indonesians awarded only 16 percent of their votes to all the Islamic parties combined, making clear to party leaders that every vote counts if they aim to bolster their positions next April.

But the alliance between Islamic parties and extremist groups is also becoming something of a political liability, as many of the recent terrorist attacks in the region have been pinned on radical groups such as Jemaah Islamiyah, a shadowy network of groups spread across Southeast Asia. Since Muslims have accounted for most of the casualties in these attacks, the Islamist political parties are now being challenged to declare where they stand in the current national fight against terrorism.

For Indonesia's political Islam, terrorism could not have come at a worse time. Islamist political parties only recently rediscovered their voice, following the downfall of the autocratic Suharto regime in 1998. Suppressed for more than 30 years under Suharto - and for six years before that by his predecessor, Sukarno - political Islam is one of several forces that have taken advantage of the country's democratization process during the past five years.

But the Islamist parties also quickly learned that their political goals - the introduction of the sharia (Islamic law) and establishing an Islamic state - did not sell well even though nearly 90 percent of the 230 million people profess to be Muslims. In 1999, only three Islamist political parties - out of more than a dozen that used Islamic banners in joining the elections - won seats in parliament. The United Development Party, the Crescent and Star Party and the Welfare Party together polled not more than 16 percent of the votes.

The Nation Awakening Party (PKB), which relied on the support of some 40 million members of the Nahdlatul Ulama Islamic mass organization, was quick to establish its pluralist credentials. The strategy paid off when PKB patron Abdurrahman Wahid was elected the country's first democratically elected president in 1999 as a compromise (his party only came fourth), precisely because of his pluralist views.

The PKB's 11 percent tally of the 1999 votes should really be lumped with the 55 percent won by the two dominant secular nationalist parties, the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle and Golkar, the party that helped keep Suharto in power for over three decades. Nationalist, secular, and pluralist political forces therefore make a formidable force of about 66 percent, judging by the 1999 election.

This alone destroys any notion that political Islam is fast gaining strength in Indonesia or that the Islamist forces are about to overrun the secular forces in the country anytime soon. Political Islam has become more vocal, for sure, but its power and influence are checked by the populace through elections. The 1999 election reaffirmed the view that the majority of Muslims in Indonesia feel much more at ease with secular parties. This result is comparable to Indonesia's only other democratic election in 1955. Masjumi, the party that unified Islamic parties, polled just over 20 percent then.

Still, garnering 16 percent of the vote gives the Islamist parties today some clout. The United Development Party, as the country's third largest party, clinched the vice presidency in 2001 after parliament impeached Wahid and installed then vice president Megawati Sukarnoputri to the top job. Islamist parties have also scored victories in some legislation, most recently in the national education bill. However, their campaign to have the sharia written into the national constitution has run aground.

Most recent opinion polls about the 2004 election show that Islamist parties have hardly gained ground over the last five years. If anything, political Islam is still too fragmented to be able to pose any serious challenge to the secular parties. And now, terrorism is posing a serious challenge to political Islam from within its ranks.

The growth of political Islam in a nation in a democratic transition has its downsides too. Political Islam comes not with one voice, but several. While most use the voice of peace, some use the voice of violence or, worse still, resort to violent practices. While Islamic radicalism represents a tiny minority in the political Islam movement, it is vocal and therefore attracts publicity that often makes it seem much more powerful than it is.

Prior to the devastating bomb attacks at two Bali night clubs in October 2002 that killed more than 200 people, Islamist parties vehemently refused to acknowledge the role played by the radical Islamist groups. Islamist politicians, including Vice-President Hamzah Haz and the chairman of the People's Consultative Assembly, Amien Rais, even came to the defense of radical groups when rumors initially surfaced of their role in the bomb attacks.

Their support slowly waned once it was established that the attacks were conducted by people associated with JI. Similarly, the Indonesian authorities have tracked subsequent bombings at a McDonald's outlet in Sulawesi in December last year and the Marriott Hotel in Jakarta in August to the same group.

While Islamist parties and their leaders have publicly condemned these terrorist attacks, they have been reluctant to openly denounce the organizations or the individuals who had, at one time or another, been their allies in political Islam.

The government's struggle to deal with the threat of terrorism would be significantly bolstered if it had the full, rather than half-hearted, support of political Islam. President Megawati has been reluctant to crack down on radical Islamic groups for fear of enraging political Islam. She does, however, enjoy the support of Nahdlatul Ulama and the Muhammadiyah, the two largest Islamic mass organizations in the country.

The failure of Islamist parties to lend their full support to the nation's fight against terrorism may have been caused by their fear of alienating small bands of traditional supporters, especially with general elections just five months away. But their failure to denounce the terrorists could eventually cost them even more votes among moderate Muslims already appalled by the endless terrorism. Their coyness towards terrorism could eventually discredit the entire political Islam movement in Indonesia. The call is theirs to make.

Endy M. Bayuni is deputy editor of The Jakarta Post and is currently studying at Harvard University with the Nieman Fellowship program for journalists.