Thais Seek Peace With Homegrown Muslim Rebels

Thais Seek Peace With Homegrown Muslim Rebels

PATTANI: Trying to end decades of conflict, Thailand's government has signed its first peace-talks deal with Muslim rebels. However, analysts are skeptical that those involved in the deal have enough influence in Thailand’s restive Malay-Muslim southern provinces to end the violence.

Recent months have seen a fresh wave of attacks against civilians and security forces by separatist insurgents following the assassination of a popular imam in November, allegedly by members of the armed forces. On 13 February, around 50 militants launched an assault on a military base in Narathiwat Province. The assault was repelled by the Marines at the base, who had prior knowledge of the attack; they killed 16 militants without taking a single casualty. But the incident underlined continuing regional instability and increasing ambitions of militants who have been waging a separatist insurgency since 2001. More than 5,300 civilians have been killed in that time, yet despite its close proximity to millions of western tourists on Thailand’s beaches a few miles north, the conflict has largely failed to register beyond the country’s borders.

One reason for that lack of interest has been the determinedly local nature of the conflict, despite attempts by international jihadist networks to establish links with the protagonists. Although fears were raised in the wake of the September 2001 attacks in New York and Washington that southern Thailand may become another theater in the so-called Global War on Terror, especially in the context of jihadist rhetoric from local militants, the insurgency has remained rooted in local grievances and identities that have proved impervious to global trends in Islamist-inspired terrorism. The conflict in southern Thailand demonstrates globalization’s limits in influencing insurgencies, for which local political circumstances remain key determinants.

The conflict zone covers Thailand’s southernmost provinces that lead to Malaysia – Narathiwat, Yala and Pattani – along with parts of Songkhla Province. The population here, 80 percent Malay-speaking Muslim, feels little kinship with the Buddhist-majority Thais that annexed their former Sultanate under a 1909 deal with the British. Many feel their culture and language are being systematically undermined by assimilationist policies emanating from Bangkok.

An armed independence movement began in the 1960s, triggered in part by the Thai state’s efforts to modernize education in the region’s Islamic schools, conducting classroom studies in the Thai language. Although the movement was militarily defeated by the early 1990s, insurgents reemerged in 2001 in a more clandestine operation, ruthlessly maintaining a code of secrecy and refusing to make clear political statements or identify the organizational structure. The militants refer to themselves as juwae, meaning “fighters.” Nonetheless, exiled groups in Malaysia are thought to have operational control over the movement. The peace-talks deal on 28 February was signed with a leader from the BRN-Coordinate, or National Revolution Front-Coordinate, a group considered to have the most influence over the fighters, although that group is split into multiple factions. It’s far from clear that other organizations will agree to talks.

Their goal remains independence for the region – more an emotional appeal than a detailed political project, based on a narrative of Thai colonialism. That narrative gained considerable currency after two violent incidents in 2004: the killing of 32 poorly armed militants in the Krue Sae mosque in Pattani and the death of 85 suspects arrested in Tak Bai in Narathiwat, most suffocating to death in overfilled army trucks. The failure of the government and army to prosecute security personnel involved in those incidents has allowed anger to fester, compounded by continuing use of extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances by branches of the security forces.

Feelings of injustice, cultural alienation and lack of political agency have ensured a steady stream of recruits to the insurgency, despite brutal effects on the local population. An estimated 60 percent of victims are Muslim, ostensibly the result of revenge attacks against those accused of collaborating with the government, though in the increasingly unstable atmosphere, many deaths are put down to criminal opportunists and petty vendettas. Buddhists are targeted in a bid to ethnically cleanse the area; security forces face frequent – and increasingly professional – ambushes on positions and patrols. One of the more shocking aspects of the insurgency has been the killing of teachers. Human Rights Watch says 157 have been killed in the past decade, often in front of students, reflecting the role of education in the conflict.

Throughout the century of opposition to Thai rule, religion has been a key marker of distinction for the local population. Violence has often been justified with reference to Koran verses and depiction of Thai rulers as “infidel.” However, experts agree that the driving force behind the insurgency is ethno-nationalism, rather than Islamism. That has its roots in the region’s religious culture, with the majority belonging to the highly traditional, but moderate school of Shafi’ist Islam. Religious identity is closely tied to local language and ethnicity – many believe that Malay is the true language of Islam. Although locals are interested in events in the wider Islamic world, as demonstrated by protests during the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, these have far less recruiting power than local issues, according to interrogation transcripts with former militants.

Indeed, the current phase of the insurgency has shown less of a global aspect than the previous generation, whose leaders traveled to the Middle East for training and established personal ties with other jihadist groups in the region, including the Indonesia-based Jemaa Islamiyah, or JI, later affiliated with Al Qaeda and carrying out the 2002 bombing of a Bali nightclub.

By 2000, when JI was attempting to build a regional network of Islamist groups, Thailand’s insurgents rebuffed it. Nor have the juwae embraced the tactics of global jihad, such as targeting civilians and westerners outside the conflict zone. In many respects, the conflict appears to belong to the previous century, wedded to narrow notions of self-determination and Maoist tactics of guerrilla warfare, neither of which appear realistic. In the wake of the recent failed attack on the military base, Asia Times argued that following Maoist doctrine into larger assaults on fixed military positions was bound to lead to disaster in a region with 150,000 security personnel and little physical sanctuary for militants to prepare attacks in secret.

While the conflict may show the limits of globalization, it does mirror a dilemma facing many governments in Asia and beyond in dealing with the legacy of ill-considered border arrangements from the colonial period. Countries that attempt to crush the resulting separatist insurgencies have found them stubbornly resilient: Myanmar has failed to defeat its myriad ethnic rebel groups after decades of brutal campaigns; India’s northeastern states have degenerated into a chaotic proliferation of armed groups. Those countries which have successfully held rebellions in check – China with Tibet or Sri Lanka with its Tamils – have done so at the cost of international condemnation, without successfully addressing underlying grievances.

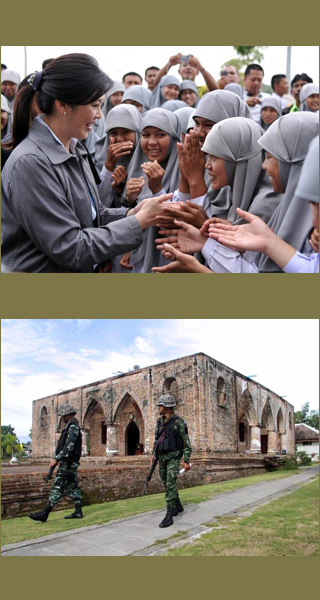

The Thai government under Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra is likely hoping that it can replicate a model from the Philippines, where the government recently achieved a ceasefire with its own Muslim separatists by promising greater autonomy for their region. Shinawatra already broke the taboo on decentralization during her election campaign in 2011, but has done little since and faces stringent opposition from conservative forces, particularly in the military.

Without better governance, simply devolving powers will do little for local citizens. But historical narratives of repression will certainly not be overcome with more repression. Many Thai nationalists fear that greater autonomy is the first step to their country’s breakup, but the alternative is continuing violence.