Transatlantic Politics of Anti-Discrimination

Transatlantic Politics of Anti-Discrimination

NEW HAVEN: Students are protesting the Trump administration’s proposed rollback of Title IX, the landmark federal legislation that prohibits discrimination in education on the basis of sex. In recent years, similar protests against university rape culture have erupted on campuses around the country. The Carry that Weight protest rocked Columbia in 2014-2015, while 2015 and 2016 saw the Stanford graduation protest condemning the lenient sentencing of student Brock Turner for felony sexual assault. In September, Yale students traveled to the nation’s capital to protest Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the US Supreme Court after three women accused him of sexual misconduct. The protesters criticize universities’ willingness to shelter perpetrators of sexual violence, a charge that resonates inside and outside the academy.

US students are not the only ones on the march. While #MeToo has brought unprecedented scrutiny to bear on the pervasive sexual violence in the media, private companies and higher education, students on both sides of the Atlantic mobilized against campus rape culture long before #MeToo took off in 2017. And many look to the United States as a model.

In 2015, for example, Trinity College Dublin conducted a survey that found one in four female students had experienced a nonconsensual sexual encounter. The Know Offence campaign was launched in University College Cork the same year, inspired by Know Your IX, the American advocacy group for survivors of rape and sexual assault in US schools. Students in England have called out the inadequacy of procedures in place to address cases of sexual violence in British schools.

The most egregious cases of campus sexual violence in the United Kingdom and Ireland have attracted national and international attention. A case at Warwick sparked outrage after women at the university learned a group of male students, in a Facebook chat, had threatened to rape and mutilate them. The men held senior positions in academic societies and sporting clubs. The university banned two of the men for a decade, but controversy erupted when Warwick announced that they could return for the 2019-2020 academic year. One woman named in the conversation criticized the response as “appalling,” and another said she was “terrified” to return to campus. The school did have a disciplinary procedure, but both men and women complained about its lack of transparency. The men had succeeded in appealing the decision, and the university did not inform the women after deciding to reverse course.

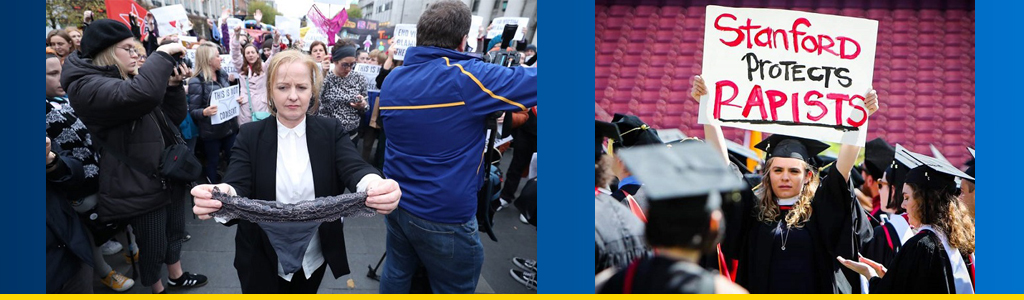

These problems in higher education institutions reflect broader societal problems in dealing with cases of rape, as revealed by a high-profile case in Belfast after a 19-year-old woman accused members of the Ireland rugby team of assaulting her. Four sets of barristers questioned the complainant over eight days in what was widely considered a hostile cross-examination. The men were ultimately acquitted, but insisted that their reputations and careers had been irrevocably damaged.

Another case of a 17-year-old reporting rape by an older man sparked protests across Ireland when the defense lawyer held up the woman’s lace underwear in court as evidence that she “was attracted to the defendant and was open to meeting someone and being with someone.” Ruth Coppinger, a member of the Irish parliament, brought similar underwear to the Dáil to protest the implication that clothing serves as proof of consent.

Universities dealing with allegations of rape and sexual assault face the same challenges. Rape is a crime that usually occurs without witnesses and is difficult to prove in court. Authorities are often reluctant to intervene in cases of sexual harassment if the violence is not physical, and rape trials themselves are adversarial. As a result, victims are reluctant to report crimes – anticipating questions and criticism about their clothes, sexual activities and relationship status.

A 2013 study by the Union of Students in Ireland suggested that one in five women in Irish third-level institutions had experienced an unwanted sexual encounter, yet only 3 percent had reported the incident to the police. The Know Offence survey found that 82 percent of students did not know how to report a case of sexual assault or harassment to university authorities. Although there was a procedure in place in University College Cork, it was neither as robust nor well known to students as Title IX is to most people in the United States. There is no similar national law to guide university policy or decide on a common standard.

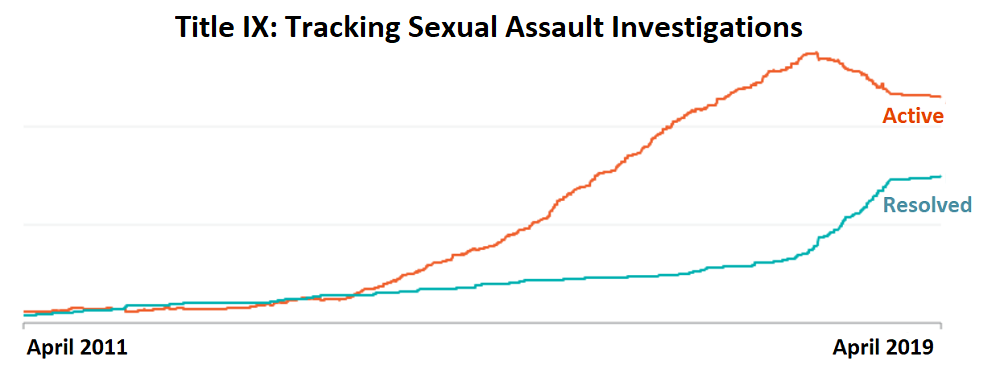

In contrast, Title IX is federal law that guides all American universities. A follow-up to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, it prevents discrimination in higher education on the basis of sex and has become the mechanism for dealing with sexual assault in US schools. Under the Obama administration, Title IX decided cases according to the preponderance of evidence standard, that it was more likely than not sexual harassment or violence occurred, in part to mitigate sexism experienced in courts. At the same time, the legislation gave accused students protections and allowed for accommodations like separating students on campus and reorganizing class schedules of both parties.

The system is not perfect. Critics of Title IX claim that the rules violate the due process rights of accused students and that rape allegations disproportionately target black men. Critics welcome the Trump administration’s proposed changes, which would make it more difficult to prove incidents of sexual assault and reduce the geographic scope for which universities are required to investigate complaints.

But these concerns are misplaced, and sometimes disingenuous. The rollback of Title IX is part of a broader agenda to dismantle protections for victims of sexual violence and promote a culture of impunity for powerful men who have long evaded accountability for sexual misconduct. A recent example at Dartmouth – where seven women have sued the university for enabling “predatory” professors to promote a “21st century Animal House” climate for more than a decade – underlines how higher education institutions have yet to reckon fully with the demands of #MeToo.

Rolling back Title IX will dismantle needed protections for the most vulnerable students in cases like Dartmouth while doing nothing to reduce racism embedded in the system. Because the new Title IX rules will make it harder to report cases of sexual violence, the most vulnerable people – trans-women, disabled women and women of color – will suffer most. These women are most likely to be assaulted and least likely to report. Because of race and gender biases, their reports are rarely considered credible when they speak out.

There are signs of change, and recent high-profile cases are shattering the impunity that powerful men enjoy. Still, most victims to come forward are white. Black women victims have been marginalized by #MeToo, as the documentary on singer-songwriter R Kelly powerfully makes clear. Even in Title IX hearings, white women’s voices are privileged. Maintaining robust institutional frameworks for dealing with sexual violence is necessary to redress this imbalance and allow the most vulnerable to hold the most powerful to account.

Title IX is a progressive policy that balances the rights of complainants and accused alike. It can be bolstered to strengthen issues of due process without dismantling the other protections it provides. Due process rights for accused students and compassionate policies for victims of sexual violence need not be mutually exclusive. Framing the issue in such a way reinforces historic beliefs that women who report sexual violence take something from men.

The public comment period for the proposed Title IX changes has closed. The review could take months. Even if the Trump administration succeeds in stripping away its protections, students around the world still look to Tile IX as a model in fighting their own battles against racist and sexist campus cultures.

Ruth Lawlor is a Fox International Fellow at Yale and a PhD candidate in history at the University of Cambridge. Her research in US foreign policy focuses on conflict-related sexual violence and is supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Cambridge Trust and the Robert Gardiner Memorial Fund.