Trump’s Impeachment: What Comes Next?

Trump’s Impeachment: What Comes Next?

NEW HAVEN: Just 14 months before he will likely stand for reelection, President Donald Trump finally faces an “impeachment inquiry” by the US House of Representatives.

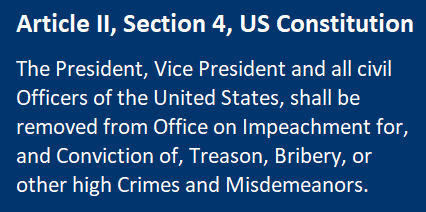

Under US constitutional law, impeachment is the first step in a constitutional process that could lead to Trump’s removal from office. Articles I and II of the US Constitution authorize the House alone to impeach the “President, Vice President, and all civil officers of the United States," to be removed upon Senate conviction for "Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors." An “impeachment inquiry,” as launched on September 24 by Speaker Nancy Pelosi, means only that under a single umbrella, a formal investigation into possible impeachment will be conducted by six key House committees that have already been aggressively investigating Trump’s activities: Financial Services, Foreign Affairs, Intelligence, Judiciary, Oversight and Reform, and Ways and Means.

Because impeachment and removal of an elected official overturns an electoral result, an impeachment conviction requires both a serious abuse of office and a supermajority vote with two key stages: First, the House investigation, hearings, debate and simple-majority vote on a resolution that includes articles of impeachment, a quasi-indictment drafted by the House Judiciary Committee. Stage Two is a Senate trial, which is not a criminal trial, but a determination whether the offenses charged and proved warrant removal. The Chief Justice presides, House members act as prosecutors – “managers” – and attorneys for the accused present defenses and question witnesses, while the full Senate sits as a “jury” that must give a two-thirds vote to convict the president and remove him from office.

The constitutional concept of impeachment is neither exclusively federal nor exclusively American. The remedy, first used by the English Parliament against Baron Latimer in the 14th century, was later adopted by the constitutions of Virginia, Massachusetts and other American states, recently enabling the Illinois state legislature, for example, to impeach Governor Rod Blagojevich. The remedy also exists under constitutional law in many other countries, including Brazil, which impeached Dilma Rousseff in 2015-2016; the Republic of Korea, which removed Park Geun-hye in 2016-2017, Germany, Ireland, India, Philippines, Russia, Ukraine, the United Kingdom, and France. The word "impeachment" itself derives from the French words empêcher and empeechier, drawn from Latin impedicare, which expresses the idea of becoming caught or entrapped.

.png)

No American president has been removed through impeachment. Only two presidents have been impeached: Bill Clinton for perjury and obstruction of justice in 1998 and Andrew Johnson for violating the Tenure of Office Act in 1868. Each was acquitted by the Senate, Johnson by just one vote. The House Judiciary Committee famously approved three impeachment articles against Richard Nixon in 1974, but before House proceedings concluded, he resigned upon release of the White House tapes.

A common canard is that an impeachable offense is whatever a majority of the House deems it to be at a given moment in history. But Trump cannot be impeached based on mere political differences with his policy views or frustration with his rhetoric. An impeachable offense must be a constitutional offense that negatively impacts the constitutional system by subverting basic political and governmental processes.

.png)

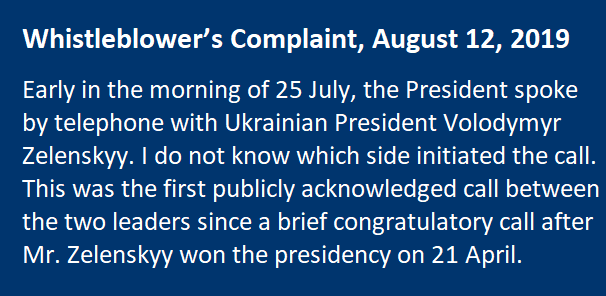

News reports suggest that Speaker Pelosi has asked the relevant committees to take a “rifleshot, not shotgun” approach: to focus narrowly on drawing up Articles of Impeachment that will charge Trump with the extortion and coverup that the anonymous whistleblower’s complaint shows and incomplete White House transcripts describe. The charge would state that by withholding foreign aid, Trump extorted Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky by urging him to investigate the Ukrainian activities of 2020 Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden’s son. Subsequently, numerous presidential subordinates took measures to cover up Trump’s actions. Thus, following the Nixon impeachment playbook, the House Judiciary Committee, chaired by Representative Jerrold Nadler of New York, could charge that Trump: 1) obstructed justice, 2) abused the powers of his office, and 3) committed contempt of Congress by persistent failure to comply with House subpoenas. The House Committee failed to charge Nixon with two other articles of impeachment that could potentially be lodged against Trump: 4) tax fraud and 5) foreign policy abuse that violated his constitutional oath to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed,” in Nixon’s case, the secret bombing of Cambodia. If the Iran-Contra Affair involved trading “arms for hostages” in an unconstitutional privatization of foreign policy, Ukrainegate involved similar privatization that sought to trade arms to Ukraine for electoral interference. If it could be proved that Trump made this particular foreign policy decision to secure something of value – i.e. electoral benefit to him by Ukraine – that would amount to both a violation of federal election laws and 6) a sixth impeachable offense, “bribery.” A bribery count could also potentially encompass payments or promises of rewards to Trump’s businesses that violate the Constitution’s Emoluments Clause, which prohibits any federal officeholder from accepting any payment or gift from a foreign state without the consent of Congress. With respect to each count, the House managers at the Senate impeachment trial would have to make fact-specific showings that the president acted in self-interest, not the national interest.

A more expansive resolution of impeachment could go back to charges and facts detailed in the Mueller Report. After all, Trump’s call to Zelensky plainly attempted the kind of “collusion” with foreign interference in an election that Trump claimed was missing with Russia. The call came just one day after Mueller’s tepid congressional testimony, suggesting that Trump became emboldened to solicit foreign electoral interference in 2020 after facing no consequences for welcoming similar interference in 2016. And the 2016 hacking of the Democratic National Committee emails eerily recalls the 1972 Watergate burglary of the same committee offices. The Watergate precedent applies even if Trump, like Nixon, did not direct persons to conduct or facilitate that burglary, so long as it could be shown that the president then used his office to thwart investigation into the burglary. But if Congress ranges too widely or fails rigorously to adhere to constitutional standards, Trump’s impeachment could be perceived as a partisan tool for undermining elected officials and overturning election results. So while the constitutional insults of Trump’s presidency have been many, Pelosi wisely seems determined to keep the inquiry swift and narrow.

The most straightforward way to achieve that goal: First, to subpoena key witnesses, as the relevant committees are already doing with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo as well as others, including Attorney General Bill Barr, White House Counsel Pat Cipollone and Trump's private attorney Rudolph Giuliani. Should the witnesses refuse to appear, these committees may seek expedited action by the courts to secure their testimonies and add to the evidence of obstruction of justice. Second, to introduce before that committee those testimonies, unredacted versions of the whistleblower's memo, transcripts of Trump’s phone calls with Zelensky, and other corroborating information in support of clearly written articles of impeachment. Third, to hold a House Judiciary Committee hearing where committee counsel put the case for impeachment simply and directly, followed by a likely party-line vote in favor of particular articles of impeachment. Fourth, to hold a timed floor debate and vote out an impeachment resolution, perhaps supported by a few Republican votes, before Congress’ 2019 Thanksgiving recess.

What happens once the action shifts to the Senate is far less clear, because of Trump’s staunch support from Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. Of course, it will be hard to find 67 votes in the current Republican-controlled Senate to support impeachment. And both political parties will have trouble sustaining energy for impeachment while a first-term president is seeking reelection. But during the campaign season, both parties may have incentives not to have a contentious Senate trial, including hearing from eyewitnesses and compelling document production. While the matter is not free from constitutional doubt, in theory, the Democratic House could vote impeachment for Trump, and pause for the 2020 election hoping that the stain will spur his defeat. If the Democrats take both the House and Senate but Trump is reelected, the House could quickly revote the resolution and the reconstituted Senate could then try and remove Trump with two-thirds of the senators present voting "guilty." If Trump were impeached but acquitted, like Johnson, he could still be censured, although Clinton was not. If Trump were convicted and removed from office, the Senate could vote to bar him from holding future federal office or receiving his pension. And as the Mueller Report made clear, neither conviction nor acquittal on impeachment charges would bar Trump’s post-office criminal prosecution.

As impeachment proceedings unfold, Trump could undertake more impeachable behavior, or more whistleblowers’ reports or news leaks could emerge that bolster the case for removal. Seventeen other federal and state criminal investigations of Trump and his past or current subordinates are ongoing, some of which might name him as an unindicted co-conspirator, as has already apparently occurred in the Michael Cohen investigation. Continuing efforts to secure release of Trump’s tax returns could unearth information that makes his core public support crumble. So too, could negative economic news or erratic foreign policy decisionmaking, especially if it threatens unnecessary war.

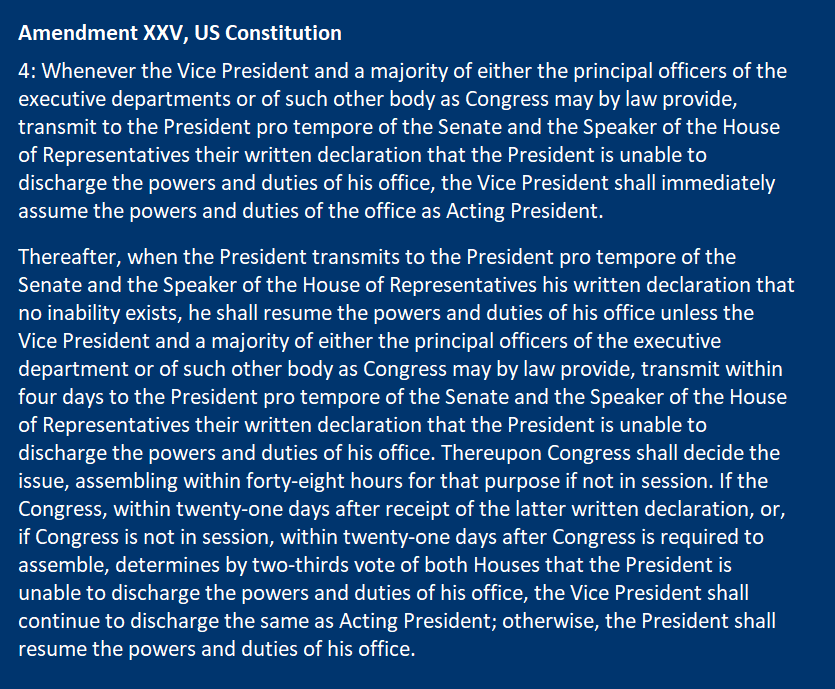

The impeachment process could well interact with other constitutional remedies. If Trump becomes more erratic as impeachment proceedings proceed, or if it became clear that he was engaging in ongoing obstruction of justice, just nine sitting executive officials could separate him from his powers immediately, with the possibility that he could permanently be separated from those powers within a month. While little understood, the never-before-used Section 4 of the 25th Amendment authorizes just nine government officials – the vice president plus eight executive department heads – to separate the president from his powers by signing and transmitting to the House speaker and Senate president pro tempore a written declaration that “the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.” Once that notification is sent, Vice President Mike Pence would immediately become acting president. Should Trump contest the claim, those charging his inability would have four days to respond to his challenge. Both houses of Congress would be called to assemble within 48 hours to debate and decide within three weeks, by a two-thirds vote, whether the president is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.

Of course, both Pence and current Republican legislators have been startlingly supine in the face of Trump’s countless escapades. But former Republican Senator Jeff Flake recently speculated that as many as 35 Republican senators would support impeachment if they could vote in private. Particularly if it starts to look like the Republican party is heading for catastrophic losses in the 2020 election, a group of prominent Republicans could emulate the famous 1974 White House visit of the “Goldwater Trio”, when Republican legislators Barry Goldwater, John Rhodes and Hugh Scott finally triggered Nixon’s resignation by telling him that he had lost all support within his party.

Over almost three long years, Trump has dodged multiple bullets, but this one is the most threatening. Last year, in The Trump Administration and International Law, I predicted that after absorbing significant punishment, the myriad forces opposing Trump’s misadventures would eventually come off the ropes – as in Muhammad Ali’s famous “rope-a-dope” fight – and knock him out politically, whether by congressional investigations or the 2020 presidential election. Time will soon tell whether we have finally reached the point where Ukrainegate becomes Trump’s Watergate.

Harold Hongju Koh is Sterling Professor of International Law, Yale Law School; Legal Adviser, U.S. Department of State (2009-13); Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights & Labor (1998-2001).

This article was co-published with Just Security blog September 29, 2019.