Tunisia Remains Arab Spring’s Lone Success Story

Tunisia Remains Arab Spring’s Lone Success Story

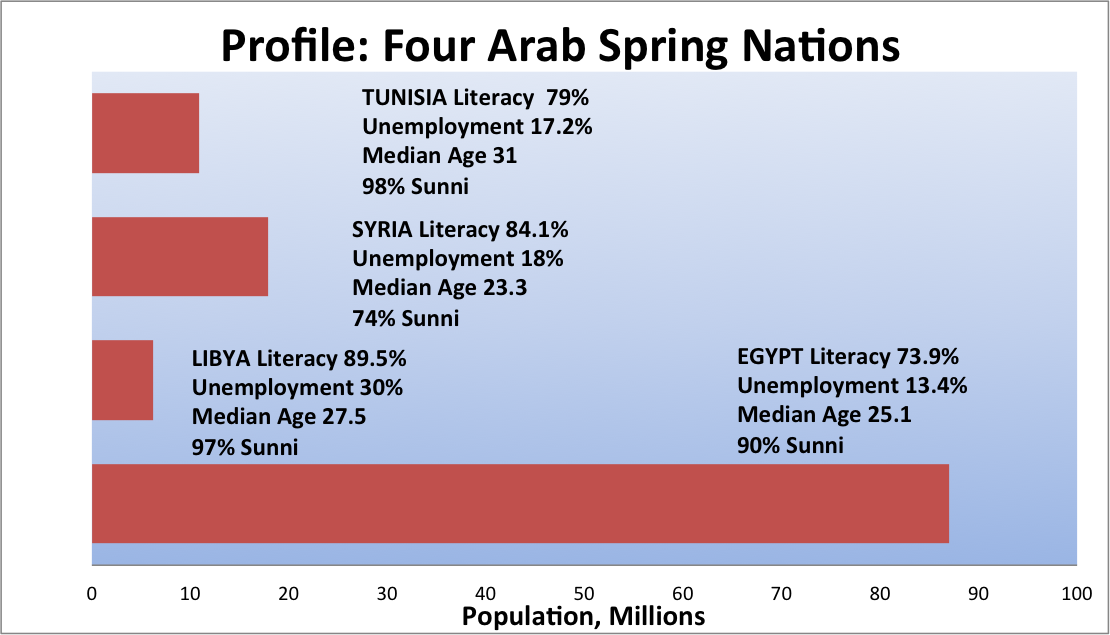

NEW HAVEN: February 11 marks the fourth anniversary of the overthrow of former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, and in the wave of protests that swept across the Middle East in early 2011, the demise of Egypt’s crony-capitalist dictator promised a new era in the region’s politics. Egypt had long been a bellwether of broader trends in the Arab world, and protesters’ success seemed to hail an era of revolt, Islamist politics and, most of all, of rapid change.

But promises can be broken. How ironic that four years later – after Mubarak’s overthrow, the election victory of candidates with the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood movement and a military coup – a period promising enormous change has ended with the return of an authoritarian regime and old ways in Egypt. The country is governed by a military-backed regime, which has ruled since former military intelligence officer and Defense Minister Abdel Fattah el-Sisi ousted Mohammed Morsi, the Muslim Brotherhood–linked president in 2013. In Egypt, “stability” is the watchword and political innovation is seen as an untenable risk.

At first glance, it might seem that all the revolutionary impulses of the Arab Spring have been squashed. All of the revolts of 2011, except for Tunisia’s, have ended in tragedy. The uprisings were quickly sullied by a region-wide clash between the Muslim Brotherhood and autocratic governments. The Brotherhood, an Islamist group with deep roots across much of the Arab world, had gained influence in recent decades in part because it provided a valuable network of social services to its members, many part of a rising middle class. A second, perhaps more compelling reason for the organization’s rise, was that in a region dominated by military autocracies and absolute monarchies, the Brotherhood was the main credible locus for opposition politics.

After the Arab Spring protests toppled established elites, the Muslim Brotherhood was the main beneficiary. In Egypt, Morsi, backed by the Brotherhood, was elected president. The Ennahda movement, linked to the Brotherhood, also took power in Tunisia. In Syria and Libya, too, groups tied to the Brotherhood made a claim on power.

In each instance, the Brotherhood faced resistance not only from domestic elites and representatives of the old regimes. The movement’s rise took on a regional dimension too, as status-quo powers such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, fearing that the Brotherhood might one day threaten their own hold on power, mobilized to oppose it.

In their war against the Brotherhood, the Gulf monarchies have funneled billions of dollars to military-backed governments in Egypt. Saudi Arabia and its allies hope that squashing the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and elsewhere will keep the lid on opposition politics across the region. To this end, the UAE has intervened militarily in Libya’s civil war, sending its air force to bomb Islamist positions near Tripoli. Meanwhile Qatar, an outlier among the Gulf monarchies, has backed Brotherhood-linked parties across the region, funneling them money and broadcasting news sympathetic to the Brotherhood on its Al-Jazeera TV channel.

The Gulf monarchies’ decision to intervene financially or militarily across the Middle East has undermined chances for peaceful transitions from autocracy to consensus-based democracy. Domestic clashes have become international ones. In Libya, Syria, and across the region, disputes are settled with increasingly heavy firepower. The influx of foreign funds and arms from the Gulf, but also from other outside powers has exacerbated existing disagreements and empowered extremists.

This dynamic not only makes less likely the types of political settlements needed to restore stability, it has also degraded many of the institutions that have held together divided states. Libya and Syria in particular highlight the risk that political struggles lead to civil war and state collapse.

It is far easier to tear down old institutions than to build new ones, as many leaders of the Arab uprisings have learned to their dismay. In Libya, for example, a revolt toppled long-ruling strongman Muammar Gaddafi, but in the process upset a delicate regional balance among the country’s regions. Once the Gaddafi-era state had ceased to exist, Libyans could not immediately replace those controls with a state that accommodated clans from each of the country’s regions. Outsiders from the Gulf pumped money and arms to their favored group, drastically increasing firepower while decreasing the chances for a peaceful resolution.

Libya instead has fractured along regional lines, with religious groups allying with some regional clans, and secularists linked with the old regime aiding others. The sources of the dissatisfaction that led to protests against Gaddafi – unemployment, corruption and bad governance – were shared across Libya’s regions. But the country’s warlords think little of addressing those concerns and focus instead on seizing territory from their opponents. The longer the conflict lasts, the less likely Libya is to be brought together as a functioning country.

If Libya showcases the risk of regional divides and state collapse, Yemen, Bahrain, and Syria highlight the risk of sectarian politics. In Yemen, for example, the Sunni-Shia split has been an important political force as the largely Shia Houthi movement has risen to power in Sana’a. Yet Syria provides the clearest example of the dangers of exploiting sectarian divides. The territory of present-day Syria has long been home to a variety of religious groups, from Sunni Arabs – who make up the majority of the population – to Christians, Druze and Alawites. The current government of Bashar al-Assad is drawn mainly from the latter group, though before the revolution it had supporters from all of Syria’s main religious sects.

When protests began in Syria in early 2011, the government in Damascus adopted a strategy of exacerbating sectarian tension to bolster its grip on power. The theory was simple: No longer able to count on the passive consent of the majority of the population, the government needed the active support of a minority. By sowing tensions among religious groups, including by targeting military operations in a way that reduced trust between Sunnis and Alawites, the government hoped to bolster support from al-Assad’s fellow Alawites.

The regime’s strategy was based on a kernel of truth: Many of the earliest anti-government protests in Syria were backed by the Muslim Brotherhood, a Sunni organization mistrusted by Alawites and Christians alike. Yet the government actively worked to turn mistrust into fear – fear that a rebel victory would drastically reshape the balance of power in the country, even fear that a Sunni-backed government might threaten Alawites’ safety. By all accounts, the regime managed to consolidate support among Alawites. Yet the country is now sharply divided on sectarian lines, and the conflict has spawned extremist groups, including the notorious Islamic State. Worse, the war has caused one of the world’s largest refugee crises in a generation. The dictator al-Assad still holds power, but over a fraction of the people he governed four years ago.

Only Tunisia appears to have ended the Arab Spring no worse than it started. The Sunni Muslim nation of 11 million avoided civil war and managed to produce democratic institutions that have so far mediated among the competing factions and ideologies. Both the Muslim Brotherhood–linked Ennahda movement and the party tied to the old regime have compromised. The recipes of Tunisia’s relative success seem straightforward: limit outsiders’ meddling, avoid sectarian politics and encourage all sides to compromise. Sadly, across the Middle East, as the Arab Spring approaches its fourth anniversary, these elements seem in short supply.

Chris Miller is a PhD candidate at Yale University and a research associate at the Hoover Institution. He is currently finishing a book manuscript on Russian-Chinese relations.