Of Two Minds on China

Of Two Minds on China

SYRACUSE: The fictional Doctor John Doolittle traveled from England to Africa many years ago and discovered a rare creature called the pushmi-pullyu. It looked something like a gazelle, but with no tail. Instead it had two heads with horns, one at each end of its body. As one head slept, the other was awake and watching. One head did most of the talking, allowing the other to eat. How such an amazing animal could walk, much less run, must have been a problem. Of course the pushmi-pullyu existed only in the imagination of Hugh Lofting, who wrote books for children.

Today’s China is something like this impossible animal with two heads facing in opposite directions. One looks toward openness and reform – freedom of expression, unfettered access to the internet and an independent legal system. It thinks that China’s continued development depends on wider acceptance of liberal values and norms. The other head believes, to the contrary, that China’s paramount need is unity and stability, guided by the Communist Party. The leadership must do whatever it takes to avoid the fate of the former Soviet Union or, for that matter, the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. To maintain its internal sovereignty and external security, Beijing must be assertive in guarding its interests.

China is pushed and pulled in both directions, but now appears to be moving on a perplexing path of more control than reform. If the continued success of its economy depends on greater creativity and innovation, isn’t it counterproductive to restrict its citizens’ access to ideas and information? If China needs to maintain smooth relations with the rest of the world for the sake of its growth and development, why run the risk of antagonizing other nations with aggressive behavior?

There are multiple theories for China’s more authoritarian domestic policy and assertive foreign policy:

-

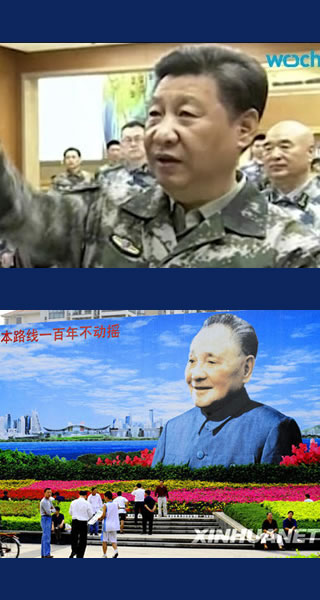

Some observers blame Xi Jinping’s rise to power. Since assuming command as president and general secretary of the Communist Party in 2012, he has purged rivals through an unprecedented anti-corruption campaign and has accumulated more influence than any leader since Deng Xiaoping. He is ruthlessly eliminating opposition in the party, state and military. The official media have cultivated a personality cult depicting him as strong, decisive and affable. While he is widely admired in China, critics view him as a dictator who rejects consensus and substitutes repression for moderation.

-

Fear that the Chinese Communist Party might collapse is offered as another explanation. According to this line of thinking, the perpetuation of party rule is the only viable alternative to a descent into chaos. If the leadership were to accept constitutional democracy and allow a robust civil society, it would undercut the party’s authority. Discipline must be imposed, which accounts for censorship of the media; arrests of dissidents; and restrictions on minorities, religious groups, and non-governmental organizations. Opponents say that the party’s suppression of dissent and attacks on liberal values are evidence of its inherent weakness.

-

Nationalism is also cited as a reason for China’s hardline direction. It is argued that nationalism is the one idea that holds China together, despite efforts to revive allegiance to socialism or cultivate Confucian traditional values like loyalty and harmony. Building and fortifying remote islands in the South China Sea reinforce China’s territorial claims, even if it is produces a backlash. Such actions provide a justification for military expenditures and deflect attention from serious internal problems. Since China now has the strength to do as it pleases, it can afford to abandon Deng Xiaoping’s dictum of keeping a low international profile.

-

China’s social instability is viewed as an additional cause. Because of massive social, economic and political change, each year there are tens of thousands of rural and urban protests over unemployment, land seizures, environmental disasters, the household registration system and other issues. Beijing’s inability to undertake fundamental reform to increase transparency and accountability has undermined faith in the government and the party. Attacking corruption, even on a large scale, only treats the symptoms, not the underlying causes of China’s unrest. The party-state’s response has been to revive policies of the past to keep the smoldering social volcano from erupting.

One might logically conclude that China’s global image is being tarnished by Xi’s centralization of power, the Communist Party’s crackdown on civil society, a more aggressive form of nationalism and growing social instability.

Yet world opinion is not so negative as some observers might imagine. Mounting concern in the West about China’s direction under Xi Jinping is not necessarily shared by others. Beijing has invested enormous amounts of money in television and print media as well as educational ventures such as the Confucius Institutes to cultivate a positive image abroad and convince the international community that its rise is not a threat. The success of these soft-power ventures is unclear, but many nations continue to view China through a pragmatic rather than an ideological lens.

According to Pew Research Center surveys conducted in 2014 and 2015, views are most favorable in countries that benefit from substantial trade, aid and investment with China. Admiration for the success of China’s state-directed capitalism is another factor in some parts of the world. Last year, 79 percent of Russia and over half of those surveyed in various African and Latin American countries were more positive than negative, as was Australia, which sells substantial natural resources to China. Pakistan, a long-time partner, was 82 percent favorable and only 4 percent unfavorable. India was ambiguous about China with 41 percent positive and 32 percent negative.

At the other end of the spectrum, countries that have territorial disputes with China are far less positive. Japan was the most negative, 89 percent, followed by Vietnam, 74 percent. Public opinion in Turkey was unfavorable, 59 percent, because of China’s treatment of Muslim Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

American opinion has turned more unfavorable, 54 percent, than favorable, 38 percent, since Xi Jinping’s rise to power. Americans are worried about the US-China trade deficit and the loss of jobs. They are also concerned about cyber attacks, Beijing’s human rights record, China’s impact on the environment and its growing military strength. Western Europe mostly shares these concerns, although France has been more positive than negative.

Global responses to China’s policies vary a great deal. Mostly positive views could quickly erode if China’s economy experiences a severe downturn. Deeper social turmoil, possibly exacerbated by the challenges of a rapidly aging population, could worsen its image. Military conflict in Asia – in the South China Sea or with Japan or Taiwan – would disrupt trade and have a chilling effect on world opinion.

But we must exercise caution in coming to conclusions about where China is heading.

China is a wondrous and perplexing creature with two heads pointing in opposite directions. One is friendly and cooperative, the other appears menacing and unpredictable. Whether these can be reconciled seems unlikely, but the past is littered with predictions that never came to pass. We only know that the future is fraught with uncertainty and the stakes are extremely high.

Terry Lautz is a Moynihan Research Fellow at Syracuse University and former vice president of the Luce Foundation. He is the author of of John Birch: A Life (Oxford, 2016), the story of an American in China who became the namesake of a controversial right-wing organization.