UN Efforts in Iraq No Walk in the Park

UN Efforts in Iraq No Walk in the Park

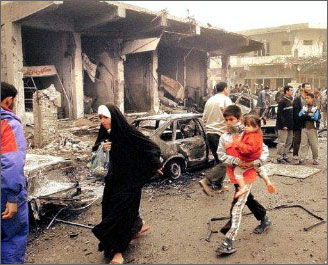

ITHACA, NEW YORK: The transfer of sovereignty to a UN-recognized Iraqi interim government and the dispatch of a newly-appointed Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General symbolically healed the rift between the United States and the United Nations. But it may be too soon to celebrate the reconciliation. The tasks facing the UN peacekeeping mission remain extremely difficult, costly, and dangerous.

The immediate question for Iraq is whether the new Security Council Resolution 1546 and the formation of a new interim government will stop the violence and stabilize the country. First indications are that they may not. Since the handover on June 30, attacks on both Coalition and Iraqi forces and civilians have continued, and casualties on all sides have risen. In a recent poll conducted under US auspices, 80 percent of Iraqis felt that security would be restored if the Coalition forces just packed up and left. Still, Prime Minister Allawi’s drastic and decisive measures may eventually pay off. These include an Order for Safeguarding National Security amounting to martial law, the support for stepped up US bombing of alleged terrorist safe havens in Falluja, killing scores of Iraqis, including civilians, the detention of 500 “criminals” and the establishment of a State Security Apparatus resembling Saddam Hussein's dreaded Mukabarat. But will these measures bring stability in time for the UN to organize the country’s first election?

Judging by history, the UN’s peacekeeping record, which consists of 43 missions in the past 13 years, is decidedly mixed. The UN has assumed all governance functions in only two cases, those of Kosovo and East Timor. Another country, Cambodia, where the UN provided the umbrella authority leading up to the election, provides a relevant historical experience to compare with the UN role in Iraq.

As in Cambodia, the UN is again being asked to help restore order and rehabilitate a country devastated by war and mass killings. A major difference, though, lies in the security situation in Iraq a year after the end of Saddam's regime and that in Cambodia after 10 years of Vietnamese stabilization efforts. The United Nations Transitory Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC), which operated in Cambodia in 1992-1993, cost $1.7 billion. It involved 16,000 peacekeeping troops, over 3,000 civilian police monitors, and 1,000 international civilian staff. Its main tasks included the holding of national elections, the demobilization of soldiers from the four Cambodian armed factions, and the repatriation of 370,000 refugees from border camps in Thailand.

Geopolitically, Iraq is also quite different from Cambodia. When the UN arrived in Cambodia in 1991, the country was stable and had had a functioning government for twelve years. In pre-war Iraq, there was the fully functioning government of Saddam Hussein, but after the Coalition victory the government was totally purged of Baathists, allegedly even nursery school teachers.

In Cambodia, Hun Sen’s 200,000-strong army and militias continued to be responsible for security. UNTAC’s 16,000-strong military component was initially tasked only with disarming and demobilizing the four armies of the Cambodian factions. By contrast, the US-led Coalition in Iraq fired all 400,000 members of Saddam’s army, sending them home fully armed. This created an untenable security situation, with soldiers suddenly unemployed and the huge weapons arsenals stockpiled by Saddam becoming available in the market for a song. The presence of some 130,000 American troops in Iraq is essential for maintaining basic security, and yet their very presence may be a source of anger and instability.

Will elections in Iraq in January 2005 herald peace and stability there as they did in Cambodia a decade and a half ago? The UN will again be involved, but this time it will have no executive powers, fewer funds for a much larger country, and much less time to prepare for elections in a much more unstable security environment.

Unlike in Cambodia, the main authority for the elections in Iraq will be vested not in the UN authority but in an independent, non-partisan, and financially fully autonomous Iraqi Electoral Commission. The United Nations will only be involved in a technical assistance capacity through a limited number of technical advisers.

At polling time it will have about 120,000 to 130,000 Iraqi individuals working on polling and vote counting at the approximately 30,000 polling stations. In Cambodia, a much smaller country, 50,000 Cambodians were employed at elections time to assist the international officers and observers who were responsible for the elections and for security. In Iraq, the United Nations will conduct an International Technical Assistance operation, but because of security considerations these advisers will be mainly stationed in Baghdad and perhaps a few other cities considered safe to operate. There are talks underway of setting up a distinct entity under the unified command of the multinational force to protect the UN operations in Iraq.

While the above scenario is necessary given the poor security situation in Iraq, it has its inherent drawbacks. The enormous authority vested in the Electoral Commission may be challenged by Iraqis – and not just by insurgents. The formation of political parties based on western concepts of democracy, for instance, may by rejected by Shiites who might want to establish a theocratic country like Iran. During the campaign period, intimidation and politically motivated murders may make the holding of elections problematic. The security situation itself can only be guaranteed if the Interim Government is able to separate the Al Qaeda foreign elements from the nationalist insurgency and deal effectively with both components. Even if security can be established for the elections itself, the absence of experienced UN officials in the field may challenge the inexperienced Iraqis beyond their capability. The UN has already established that it will not send its own observers to the field. Whether thousands of International Polling Stations Observers will be sent to Iraq has to be determined by security conditions at polling time and the willingness of international observers to serve there.

The process after the election in Iraq will also be longer than it was in Cambodia. The Iraqi elections on January 31, 2005 will produce a Transitional National Assembly which will form a Transitional Government of Iraq and draft a new constitution. This will be put to a public referendum in October 2005, to be followed by National Elections for a constitutionally elected government in December 2005.

In Iraq, therefore, even assuming the best immediate outcome of peaceful, fair, and open elections, a period of instability is most likely if not almost inevitable. It is too much to assume both that in the course of a year of UN-supervised electoral exercise Iraq will morph into a stable democracy and that the US-led Coalition and the UN would be able to walk away declaring success. Given the country’s deep divisions and its continued strategic value to both the global oil trade and global terrorism, there will be the need for a long period of international aid and monitoring.

Benny Widyono, PhD, was the United Nations Secretary-General’s Representative in Cambodia from 1994 to 1997. He is now a visiting fellow at Cornell University writing his memoirs of his experience in Cambodia.