UN Inspection in Iraq Was No Sham

UN Inspection in Iraq Was No Sham

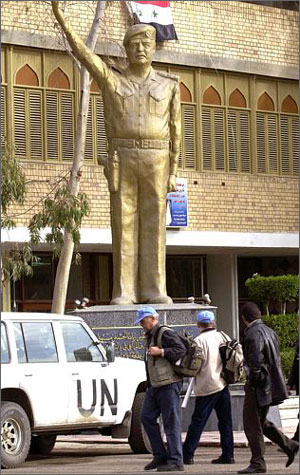

WASHINGTON: In the months before invading Iraq, Bush administration officials dismissed UN inspections there as a "fool's errand" and a "sham." Amidst the mounting evidence that US intelligence on Iraq's weapons of mass destruction was horribly wrong, one central truth is still largely unappreciated: While the world's best intelligence services were getting it wrong, United Nations inspectors were getting the picture in Iraq largely right.

International inspections in Iraq stand out as a rather striking success in the record of international endeavors of recent decades. In 1991-98, while facing unrelenting Iraqi obstruction, UN inspectors discovered and eliminated most, if not all, of Iraq's unconventional weapons and production facilities, and destroyed or monitored the destruction of most of its chemical and biological weapon agent. Iraq's most secret program - its biological weapons program - was discovered through painstaking detective work. The United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM) also uncovered covert transactions between Iraq and more than 500 companies from more than 40 countries - a body of work that assumes fresh significance in the light of recent disclosures of the nuclear sales network of Pakistan's A.Q. Khan.

In the months immediately preceding the war, the UN's assessments of Iraq's programs were remarkably close to what has since been found. The UN Monitoring, Verification, and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC) was only permitted to operate for a matter of weeks at full strength. But to the best of present knowledge, the inspectors were in the process of finding and beginning to dismantle what was there.

This record suggests a number of lessons - positive and negative. First, it appears that a package of international restraints - sanctions, procurement investigations and export/import controls combined with core inspections - worked together in a way that is not yet understood, and that this package was considerably more effective than has been appreciated then or since.

Second, even though UNSCOM and the early International Atomic Energy Agency's inspections operated under a degree of Iraqi obstruction that the Security Council should never have tolerated, the UN inspections' greatest area of weakness lay in New York, not in Iraq. Iraq played a highly effective game of divide and conquer in the Security Council, setting the permanent members against each other until political support was so undermined that inspections were forced to a halt in 1998. The lesson is clear. Political unity backing inspections is even more important than technology and expertise on the ground.

Third, the relationship between international inspections and national intelligence agencies needs a thorough review. A means for regular two-way communication between the inspectorate and national intelligence agencies must be set up - means that will fully protect the information provided, protect against penetration and misuse both by the target government and by the governments providing information, and allow feedback between intelligence providers and inspectors as discoveries are made and defectors come to light. Still pending in the Iraq case is the rather urgent question: How much of what inspectors knew did United States intelligence know and, if there was key material the United States didn't learn, why not?

Fourth, if inspections are to be undertaken again, there needs to be a better understanding of the process by governments and by the public. In the Iraqi case, it was widely perceived as a hopeless chase after easily hidden needles in a haystack, and therefore easily ridiculed and undermined. Before becoming head of the United States Iraq Survey Group, David Kay wrote that "Even the best [UN] inspectors have almost no chance of discovering hidden weapons sites such as these in a country the size of Iraq." Yet the perception that inspections consist of running from place to place is not the reality. Lengthy interviews, building relationships with key individuals, building up a story from individual to individual, procurement investigations, and highly technical analysis: all of this is of the essence.

Fifth, cost needs to be evaluated, and particularly, cost for results achieved. UNSCOM's budget was $25-30 million per year. UNMOVIC's was about the same for the four months it operated. The announced cost of United States inspections over the past year is about $900 million - roughly a thirty-fold difference. UNSCOM was definitely under-equipped, and the IAEA has been chronically underfunded for a decade. But even making a generous allowance for needed improvements, UN inspections look like a high productivity operation if properly designed and backed, as compared to US inspections, and especially as compared to the $250 billion cost of the war and its aftermath.

For these reasons, the following needs to be done now:

First, the UN Secretary General should charter a detailed review of the inspections process - an after-action report. The relative value of site visits and analysis needs to be clarified. The various strengths and weaknesses of this pioneering international effort need to be fully understood, including its human resources, access to technology, relations with national intelligence agencies, vulnerability to penetration, and more.

Second, the United States and the United Nations should collaborate to produce a complete history and inventory of Iraq's WMD and missile programs. To do so, UNMOVIC personnel should be working on the ground with the Iraq Survey Group. An UNMOVIC report to the Security Council in early March makes clear that it has not been contacted in any way by the Iraq Survey Group. As the United Nations is reinserted into the political transition in Iraq, one hopes that the relationship on this front, too, can be repaired.

Third, in this joint effort, particular attention should be paid to discovering which of the several international constraints on Iraq were effective and to what degree, and to how they worked as a package.

Finally, an accurate story of the US and British intelligence failures can never be pieced together without the various investigations having full access to the United Nations archive. None of the more than half dozen investigations now underway in Washington are taking steps to do this, and the same seems to be true in Britain. On its side, the UN should facilitate that access.

Based on the results of these reviews, serious consideration should be given to the creation of a permanent United Nations inspections and monitoring body. Inspections are not a panacea. But international inspections appear to be an invaluable component of an effective, layered defense system against proliferation. Intelligence from a distance - no matter how good - can never do what a physical presence on the ground, armed with an international writ and unfettered access, can do.

A permanent, international, non-proliferation inspection capability would provide vital enforcement - hence seriousness - to the broader nonproliferation regime, and fill the gaps between the various weapons treaties. Proliferation concerns over Iraq, Libya, Iran, Pakistan, and North Korea all point to the need for such an established - not ad hoc - capability.

Crises such as those we have lived through in the past few years and months have a silver lining. They jolt the system and create a moment when political will is fluid and can be reshaped. This is a moment when change is possible. With sufficient leadership - from the United States, but not just from the United States - change can be achieved.

Jessica T. Mathews is president of the Carnegie Endowment for International

Peace. She has specialized on non-proliferation issues for many years and in

2002 was principal author of a widely noted proposal for “coercive

inspections” as an alternative to war in Iraq.

This article is adapted from the keynote address to the International Peace Academy Conference, Weapons of Mass Destruction and the United Nations: Diverse Threats and Collective Response on March 5, 2004. The complete text, with additional recommendations is available at www.ceip.org.