The US and Iran in a Tantalizing Dance

The US and Iran in a Tantalizing Dance

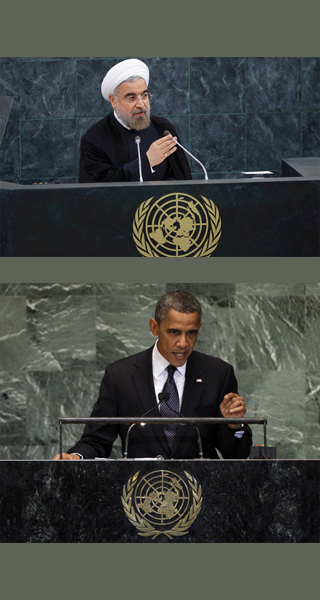

NEW HAVEN: President Hassan Rouhani’s speech to the United Nations General Assembly promises a sea change after 33 years of troubled relations between the Iran and the United States – and perhaps a new start over issues ranging from stalled nuclear negotiations to the Syrian crisis and, one would hope, the sad state of human rights and individual freedoms for Iranians.

Both sides show positive signs, but poisonous vibes are not rare either, be it editorials of hardline dailies in Tehran or the alarming statements of Israeli Premier Benjamin Netanyahu and his supporters in the US Congress. Symbolic gestures such as the release of prisoners of conscience, though mostly insiders who had gone awry, and Jewish New Year greetings sent over Twitter are part of Rouhani’s “charm offensive.” New appointments such as Mohammad Javad Zarif as minister of foreign affairs and other level-headed officials in non-ministerial positions are also promising even though the new cabinet is not completely free of figures with dark political histories.

Rouhani not only enjoys the mandate of the majority of the Iranians as the only presidential candidate who spoke of moderation, but also the conditional blessing, albeit grudgingly, of the Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. In a recent public statement Khamenei gave a green light to Rouhani, but cautioned him to exercise a strategy of “heroic flexibility” in dealings with the United States and the European Union. Not long ago, of course, while Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was still the favored son of the Revolution, Khamenei often labeled Americans, and at times Europeans, as “enemies” with whom no deal could be made.

The Supreme Leader – constitutionally accountable to no earthly authority and certainly not the will of his own people– went so far as unambiguously backing the new president in his demand for the Revolutionary Guard to stay out of politics. This may be seen as a signal for a freer press, more individual freedoms, and less intervention and favoritism in the economy. Khamenei has made no similar concession during his 24 years as the Guardian Jurist.

This change of heart – driven by a cunning pragmatism long practiced by the revolutionary clergy – emerged because of the ravaging realities of today’s Iran: social disillusionment, political isolation and an economy in serious trouble, thanks to the state’s mismanagement and debilitating international sanctions. Moreover Iran’s new middle class, with its own youth culture, is no longer content with hollowed revolutionary slogans of the past. Political demands for a fair election were abundantly clear in June 2009’s widespread protest movement against rigging ballot boxes which kept Ahmadinejad in office. The 2013 election results confirmed public repulsion for rampant corruption and mismanagement, favoritism and skullduggery under Ahmadinejad. If any more catalyst was needed, it came with Western-imposed sanctions that crippled the Iranian economy and disrupted lives of ordinary people. Soring prices combined with banking restrictions, volatile rates of exchange, and shipping insurance bans reduced Iran’s oil exports well below 50 percent, compared to 2010 figures. In effect, the sanctions deprived a rentier state of its addictive oil revenue. For decades, the free flow of oil had allowed the clerical elite to project an image of power toward its own citizens and gestures of defiance, often futile, toward the outside world.

Facing an array of domestic and international challenges, the new president has a relatively narrow window, perhaps no more than six months to a year. But he has some leverage, no doubt, in his negotiations with the United States and its allies. Iran could be a key player in reining in the Syrian regime. Flexibility on the nuclear issue may also persuade the West to ease sanctions and offer economic incentives even though, as often observed, mending a long damaged fence may take a long time – and even longer for the US administration to assure Israel and the US Israeli lobby of the new Iranian government’s goodwill. President Barack Obama’s warning in his speech to the UN General Assembly that the United State does not tolerate the production of weapons of mass destruction, should be seen as an attempt to address these concerns. Rouhani’s references in his speech to tolerance, mutual respect, peace and non-violence, on the other hand, indicated a desire for fruitful negotiation and settlement of old differences.

Judging by the experience of three earlier administrations in post-revolutionary Iran, Rouhani is facing a difficult course. Mahdi Bazargan’s Provisional Government was brought down after eight month in office at the outset of the 1979 hostage crisis, and he and his cohorts, labeled as “compromising liberals,” were banished by Ayatollah Khomeini to political wilderness from which they never returned. The presidency of Abolhasan Banisadr was doomed from the start even after receiving Khomeini’s momentary blessing in February 1980. Thanks to the militant clergy and lay allies, his political end came 15 months later with his dramatic flight to exile in Paris. And 16 years later, Mohammad Khatami’s moderate, albeit feeble, presidency was contained to the point of inaction by a radical trend almost a year after he assumed presidency. Undermining Khatami’s government eventually brought Ahmadinejad to power and made possible his farcical style and messianic message.

The window of opportunity may close even sooner for Rouhani once the hardliners around the Supreme Leader have licked their wounds and regrouped. If Rouhani cannot deliver even a mild version of what he promised, he will be vulnerable to attacks from opponents. Making headway with nuclear negotiations, relaxing sanctions and improving the domestic economy all depends on a large extent on the international community, and in particular the United States, and their appreciation of Rouhani’s quandary. His failure may very well result in greater militancy and deeper resentment and may even trigger a military strike that would be disastrous to Iran, to the security of the region and to the United States’ standing in the Middle East.

Beyond the good will of the international community, Rouhani’s success or failure may hinge on a systemic problem in Iran’s ancient political culture. Since the emergence of the office of the minister, or vazir, in early Islamic era, there has been a fundamental tension between rulers – be it sultans or shahs – and the minsters that headed the state administration. Claiming divine mandate, the rulers were unaccountable to their subjects even though they were expected to preserve the social order, and maintain peace and security. The ministers, who may well be compared with presidents in the Islam Republic, on the other hand, were not immune from the ruler’s rebuke, dismissal and even loss of life. The tension between the two offices, ruler and administrator, led in Iranian history to many ministerial casualties prompting the notion of “vaziricide,” or “killing of the chief minister.” The mid-19th century murder of the celebrated Chief Minister Mirza Taqi Khan Amir Kabir is only one noted example. The conflict between Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi and the celebrated Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq, with its tragic outcome, is another.

Rouhani’s political future may well fall victim to the same systemic tension. Or, if domestic and international circumstances give him sufficient time and a winnable chance, we may yet see, after decades of post-revolutionary exhausted rhetoric, a new political maturity that could overcome the demons of a Manichean political culture.