US Foundations Boost Chinese Government, Not NGOs

US Foundations Boost Chinese Government, Not NGOs

HONG KONG: Since the end of the Cold War, US-based foundations seeking to promote democracy and freedom through their grant-making have increasingly favored nongovernmental organizations and civil society. But perhaps nowhere is the contradiction between the professed goals of the grant-making foundations of the West and actual practices more obvious than in the case of China. It’s been long assumed that civil society organizations are key to improving basic human welfare and promoting democratic governance in developing nations. However, a study of the role of US grantors shows that attention to government-backed NGOs in developing countries, especially China, has a taken an opposite course.

On the surface, US donor interest in China is no exception to the global promotion of NGOs and civil society by philanthropic foundations. Among such donors are the Gates Foundation for HIV prevention, the Alcoa Foundation for “projects and partnerships with NGOs around the world” and the Ford Foundation for “a focus on poor and disadvantaged groups.”

Yet, in the world’s largest authoritarian state, major US foundations tend to award large grants to established organizations either controlled by the Chinese government or under its influence rather than independent or grassroots NGOs.

In China, the 1990s saw a dramatic increase in the creation of oxymoronic “government-organized non-governmental organizations,” or GONGOs. From Beijing’s standpoint, such groups can serve as tools for domestic control of new social forces while also attracting foreign funds for programs the Chinese government itself is unwilling to support.

Yet over the past decade, growing numbers of bottom-up grassroots organizations have emerged. These non-governmental organizations have not been created by nor officially incorporated into the party-state. They sometimes engage in advocacy, but most frequently focus on much-needed social services in fields like health and disease, labor rights, environmental protection and education.

Because grassroots NGOs can provide alternative spaces for political organizing and mobilization, some Chinese officials view them as a serious threat to the regime. The legal requirements for registration are, in practice, prohibitively stringent for those that might wish to become properly registered legal entities. Many are forced instead to register as businesses or operate without legal identity. Unregistered groups run the political risk of being branded “illegal organizations,” while those registered as businesses risk being shut down for fraudulently presenting themselves as nonprofits to their funders and the public.

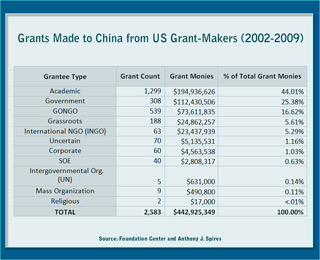

US foundations have tended to keep radical organizations at arm’s length at home while supporting hierarchical and professionalized grantees that can work within existing institutional structures. In China, the pattern is similar.

Despite rhetorical support for local efforts to build a real civil society – the Ford Foundation, for example says, “We focus on helping poor communities, women, migrants, minorities and other groups to... access the services they need through civil society organizations” – US foundation giving has almost entirely bypassed China’s grassroots groups. Between 2002 and 2009, American foundations sent almost $443 million to China-based grantees. During these eight years, government-controlled groups were the favorite of grant-makers (see Table 1). Together, academic, government and GONGO grantees accounted for 86 percent of total grant monies. By contrast, grassroots NGOs received 5.61 percent of the total.

The top ten grantees were, likewise, dominated by government-controlled institutions, taking more than 35 percent of the grant funds (see Table 2).

Although GONGOs may outnumber grassroots groups, a recent study led by myself and colleagues at the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s Centre for Civil Society Studies identified almost 300 grassroots organizations in Guangdong, Yunnan and Beijing. Extrapolating to the national population of 1.3 billion, this implies the existence of several thousand grassroots NGOs in China – all potential grantees of foreign donors. Regardless of the numbers, however, the stated priorities of donors would suggest that such groups should be among those receiving funding, not overlooked or avoided in favor of GONGOs, academic institutions and government agencies.

Donor rhetoric and actual funding choices seem to run in opposite directions.

Institutional factors certainly play a role. When making international grants, US foundations are required to support the equivalent of US nonprofits or take full responsibility for ensuring that all grants are used for charitable purposes. Many grant-makers find the latter too great a risk and prefer to deal with foreign groups properly registered as NGOs, or with government agencies and academic institutions that – by their nature – are meant to serve the public good.

Rules and regulations aside, other factors include the personal experiences and preferences of those who run US foundations. Once in China, such donors often face a huge cultural gap and immense language barriers. They find it easier to overcome such obstacles by seeking organizations whose goals, functions, organizers and experiences seem similar to their own. US funders generally represent bureaucratic organizations of professional elites with high levels of education and social, economic or political influence, and they gravitate toward partners in China with similar backgrounds in similar organizations.

Donors thus turn to academic institutions under the assumption that they’ll find open, progressive minds amenable to their agendas – building civil society, reforming the legislative process, empowering women or some other development cause. Likewise, they’re drawn to government agencies for political reasons, to avoid rocking the boat so much that they will be expelled. They are drawn to GONGOs – often staffed by government officials and academics – because they assume these are within the system and therefore carry out development work effectively.

Tellingly, almost 70 percent of the funds sent to China from 2002-2009 went to organizations in Beijing. This priority may reflect a bias towards organizations that are deemed safe, with many under the direct or indirect control of China’s central government. At the same time, the leaders of US foundations – who from time to time may hold positions of political importance in the US – look to Beijing as the natural place to begin grant-making efforts in China. These leaders hope to find in the political capital recipients who match their status and influence.

Aiming to make a difference in China, many US donors seek out people who “speak our language” or “share our goals.” This kind of rhetoric, one experienced funder acknowledges, “indicates a certain level of education and exposure.… Most of the time it means, ‘They think like we do. They’ve had exposure to the West. And they’ve learned to see things from our perspective.’”

Ultimately, while there are many strategies available to donors who wish to nurture improvements in Chinese society, pursuing systemic change through influencing policy is one potentially effective way to improve the lives of more than a billion people. Clearly, however, when US-based funders favor officially-sanctioned, professionalized and bureaucratic grantees that look and talk much like themselves over grassroots civil society organizations, they may be missing an opportunity to support some of China’s most innovative groups and the visionary people who lead them. While government partners can certainly be effective in some fields, denying grassroots groups the support they need is holding back the broader good of society that grant-makers say they aim to nurture. Unless such patterns change, the impact of US grant-making on Chinese society as a whole will be limited, at best.

Anthony J. Spires is associate director of the Centre for Civil Society Studies and assistant professor of sociology at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. A more detailed treatment of the issues is in the September 2011 issue of The Journal of Civil Society.

A Response By John Fitzgerald of The Ford Foundation:

The Ford Foundation welcomes critical scrutiny of its record in China over the past thirty years. The more the better. To encourage scrutiny, the Foundation makes detailed grant information available to all comers through its website and publications. These records are a useful point of entry for exploring what we do in China. But as most of the doing is done by others – our grantees – we especially value researchers who go beyond desk-top surveys to explore what people in China do with our grants. Our grantees’ record of achievement in China speaks for itself.

In a recent posting on Yale Global, Chinese University of Hong Kong Professor Anthony Spires cites the Ford Foundation website to argue that despite “rhetorical support for local efforts to build a real civil society” in fact the Foundation helps to maintain “the world’s largest authoritarian state” by channeling its grants to organizations linked to or controlled by the government. Reasonable people would conclude from this argument that the Ford Foundation was hypocritical, in saying one thing and doing another, and was in no sense committed to the development of an independent social sector in China.

We welcome criticism concerning the effectiveness of our strategy but the charge of hypocrisy goes to our reputation and that of our partners in China.

Our China strategy is to support work in law, governance, education, environment, US-China relations, and sexuality and reproductive health, in addition to the development of civil society. That said, our work in building the social sector is important to our overall efforts. And openly proclaiming support for the development of civil society in China is not something you say lightly if you are a foreign donor. If you say it you had better mean it.

In support of the claim of Ford Foundation hypocrisy, Mr Spires tabulates data from the Foundation’s published archives of grants along with those of other foundations. The warrants connecting the archival evidence to claims of misrepresentation are, first, that support for the NGO sector is to be measured by direct grants to small grassroots NGOs; secondly, that broad classification of archival evidence by grantee demonstrates donor intent and activity on the ground; and third, that Ford and other American donors share a natural affinity with the Chinese government due to their poor language skills and to the personal experiences and preferences of donors converging with those of Chinese authorities, to the detriment of grassroots NGOs. Each of these claims invites scrutiny in turn.

When it comes to building the social sector, our experience has taught us that increasing grassroots NGO dependence on foreign donors is not a sustainable strategy for the development of the sector. Today, many wonderful NGOS are sadly shriveling as foreign donors withdraw from China.

Our position on this point is no secret. Mr Spires overlooks a statement about our China civil society program, published on the Foundation’s website, which states that we do not directly fund small-scale projects or services undertaken by civil society organizations. We are delighted when charitable organizations from around the world fund Chinese NGOs to do good work of every kind. But this is not what we do – nor what we say we do – so the charge that we say one thing and do another does not stick.

Instead, we invest in the soft infrastructure of civil society development in China – those who build research centers, start up support institutions, launch information transparency agencies, create funding chains linking domestic philanthropy and government contracting to grassroots NGOs, contribute to policy debates and regulatory reforms, draft best-practice manuals, and so on. As a rule, we do not support small grass roots organizations for this kind of work because they don’t build infrastructure. That said, where grass roots NGOs do undertake this kind of work, we do support them.

The assumptions around data classification are equally questionable. First, Mr Spires aggregates data for all foundations but isolates particular foundations for comment. There may be other data supporting these particular claims but they are not presented. Historically, our Chinese grants are distributed about 1:1:1 among universities, research units and think tanks, and NGOs and GONGOs. Direct grants to government are negligible.

Second, universities, think tanks, and research institutes in China are included alongside government ministries as categories of government in Mr. Spires’ analysis. The same could be said of our China-office grants to universities in the US, many of them state institutions. UC-Berkeley is presumably classified as a state institution along with Tsinghua University. I would not wish to suggest that US universities operate under the same degree of government scrutiny as universities in China. Still, what does this classification tells us about actual grant activities other than that the hosts are somehow connected to governments ? Indeed, what are universities doing with our grants? A little more shoe leather would have shown what grantees are up to in China’s universities, research institutes, NGOs and GONGOs. We suggest researchers ask our Chinese grantees.

Finally, the claim that large foundations prefer dealing with the Chinese government because language barriers and personal preferences push funders toward their “elite counterparts in China” is misleading and unnecessarily elaborate. All Ford Foundation officers are fluent in Chinese and our grant business is routinely conducted in the Chinese language. Further, and leaving aside the Ford Foundation for a moment, Mr Spires offers an elaborate theoretical explanation for the observation that large American donors do not allocate thousands of modest grants to many tens of thousands of unregistered non-profits in China. We have made a strategic choice not to do so. For other American donors, a simpler explanation could be that a foreign donor cannot transfer a foreign currency grant into the Chinese bank account of an independent unregistered non-profit organization in China. This has nothing to do with the institutional culture of American foundations, which routinely make payments into the bank accounts of independent non-profit organizations in other countries. A contextual explanation relating to local foreign exchange and banking regulations would have been more elegant and accurate.

None of the warrants linking the archival evidence to Mr Spires’ conclusions bears close scrutiny. We welcome closer scrutiny ourselves, particularly by researchers who go the extra step, and ask grantees what they are doing, why, and with what effect.

John Fitzgerald is representative of the foundation’s office in Beijing. He develops the overall strategy and direction of the foundation’s work in China, which emphasizes opportunities for poor and marginal communities to participate fully and equally in China’s development. His individual grant making focuses on U.S.-China relations and civil society issues, aiming to build new-generation expertise on the United States and China, and to support Chinese institutions in strengthening domestic infrastructure for the lawful development of civil society.