US-Pakistani Relations in Crisis – Part I

US-Pakistani Relations in Crisis – Part I

WASHINGTON: Worsening relations between the US and Pakistan and the closure of the NATO supply line to Afghanistan through Pakistan have offered new leverage to Russia, but also increase the risk of instability along its neuralgic border region.

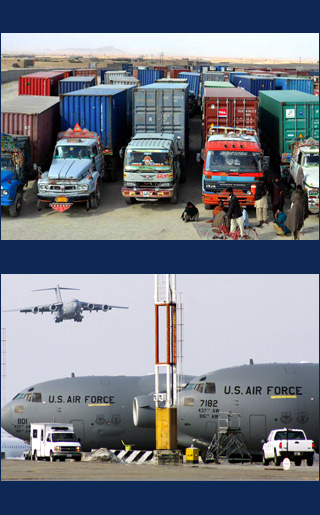

NATO operations in landlocked Afghanistan are critically dependent on the supply line that runs through Pakistan. Since 2001, most NATO non-lethal supplies bound for Afghanistan have travelled through Pakistan, but since 2008 Western governments developed alternative, albeit more expensive and lengthier, sea, ground and air transportation routes to Afghanistan’s north through territories of the former Soviet Union. This so-called Northern Distribution Network, or NDN, now conveys large quantities of non-lethal supplies from Europe to NATO troops in Afghanistan through Russia, the Caucasus and Central Asia.

Instability along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border and the recent closure of all supply routes through Pakistan after NATO forces killed 24 Pakistani soldiers on November 26 have led to increased reliance on the NDN. Even before the latest incident, Western governments had sought permission for the reverse flow of transit along the NDN so that their forces could exit through the former Soviet republics rather than Pakistan, where they’d be more vulnerable to retaliation by the Taliban and its Pakistani allies. NATO diplomats are also seeking to expand the volume of cargo sent along the NDN and include lethal supplies such as weapons.

Russian policymakers may now take comfort from the fact that NATO’s Afghan mission is hostage to Moscow’s good will. As early as two years ago Lieutenant General Leonid Sazhin, analyst for the Russian Federal Security Service, observed: “If the Khyber Pass and the road to Kandahar get blocked by the Taliban, then the US and NATO have no choice of other ...alternative routes through Central Asia. And as airplanes can’t deliver much, ground transport corridors are necessary and here Americans need Russia.”

The NDN cannot function without access to Russian territory or in the face of Russian opposition given Moscow’s decisive influence in the former Soviet republics in Central Asia. From the perspective of meeting NATO’s logistical needs in Eurasia, Moscow is in a pivotal position. Despite the vast distances involved, Russia has good transport links to Central Asia, from which goods can be reshipped by rail, road and air into Afghanistan.

Since the so-called Russia-US “reset,” the détente initiated by Washington in 2009, Moscow has allowed Western governments to send supplies to their forces in Afghanistan through Russian territory in exchange for financial compensation. Moscow also hopes to gain leverage over NATO and other benefits elsewhere – such as deferring further NATO membership enlargement in the former Soviet Union.

Russian policy regarding Afghanistan stems from its own security considerations and from perceived opportunities to advance its interests. Russians would like the International Security Assistance Force to succeed in Afghanistan and do not want the Taliban to return to power. They tend to blame pervasive terrorism and Islamist extremism in Russia’s Muslim majority regions to external sponsors rather than internal causes. There is evidence that Chechen rebels have been trained in Taliban/Al Qaeda camps, and Russians fear that a Taliban victory could increase this threat.

Assisting the NDN also improves Moscow’s ties with Afghanistan and the West. Some Russian companies earn considerable income by servicing the NDN or by selling fuel and other supplies to NATO and Afghan governments.

Russian officials are generally satisfied with their improved ties with Washington, but essentially view “the reset” as a process by which the Obama administration corrects what Russians see as Bush administration mistakes in pushing for NATO membership for Georgia and Ukraine and for deploying missile-defense system components in Poland and the Czech Republic. Russians aim to use their leverage over NATO’s Afghan supplies as a means to reinforce this lesson.

Russian officials are also pressing NATO to do more to curtail Afghan narcotics trafficking. Thousands of Russians die each year from imported Afghan opium or its heroin derivative. Russians want NATO to eradicate the poppy crops through aerial spraying of herbicides despite coalition fears that would only bolster Taliban recruiting. They also demand that NATO work with the Moscow-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) to address this threat.

The demise of Moscow’s power in Central Asia, starting with its loss of the Soviet-Afghan War in the 1980s foreshadowed the downfall of the Soviet empire and the onset of a period of diminished Russian influence in the world. Vladimir Putin considers his success in enhancing Moscow’s political, security and economic interests in Afghanistan, Central Asia and the Caucuses a manifestation of Russia’s renewed great power status.

Many Russians remain concerned about NATO’s influence in these regions. Russians do not want NATO to establish a permanent military presence in Afghanistan, Central Asia or the South Caucasus. At December’s meeting of CSTO, member governments decided that unanimous consent was required before a non-CSTO country could establish a base in a member country. At present, the only foreign base in a CSTO country is the US airbase at Manas, Kyrgyzstan. Newly elected Kyrgyz President Almazbek Atambayev has said he wants the Pentagon to leave the base in 2014.

Russians do not want any more NATO bases in what it regards as its “sphere of influence.”

At present, the Russian government’s stated position is that Moscow expects most if not all NATO troops to leave the region once they have stabilized Afghanistan. Russia’s ambassador to Afghanistan, Zamir Kabulov, succinctly observed that “It’s not in Russia’s interests for NATO to be defeated and leave behind all these problems.... We’d prefer NATO to complete its job and then leave this unnatural geography.”

Until then, Russian officials have sought to leverage NATO’s dependence to influence the alliance’s activities and policies. Russia repeatedly suggests that Moscow could suspend access should Western governments encroach on Russian interests, such as further enlarging NATO’s membership.

Observers suspect that Russian representatives at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit in June 2005 encouraged Uzbekistan to expel US military forces from its territory. The Uzbek government issued the expulsion order the following month with a180-day deadline. They also believe that some Russian officials have subsequently pressed Kyrgyzstan to end the Pentagon’s access to Manas.

The one constraint on Moscow’s behavior is that Russians fear that NATO governments will simply return to their strategy of the 1990s, declaring victory and then abandoning Afghanistan as a regional mess. In January 2010, in a New York Times opinion piece Boris Gromov and Dmitry Rogozin warned, “A rapid slide into chaos awaits Afghanistan and its neighbors if NATO pulls out, pretending to have achieved its goals.” Gromov, governor of the Moscow region, commanded the 40th Soviet Army in Afghanistan. Rogozin, Russia’s ambassador to NATO, noted, “A pullout would give a tremendous boost to Islamic militants, destabilize the Central Asian republics and set off flows of refugees, including many thousands to Europe and Russia, as well as worsen the regional narcotics problem.”

Russia provides at best instrumental support for NATO’s Afghanistan mission. Should the alliance’s stabilization effort succeed, the Russians would be first to demand the departure of Western troops.

Richard Weitz is senior fellow and director of the Center for Political-Military Analysis at Hudson Institute. His current research includes regional security developments relating to Europe, Eurasia, and East Asia as well as US foreign, defense and homeland-security policies.