US Trade Policy: Legacy of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice

US Trade Policy: Legacy of the Sorcerer's Apprentice

DURHAM, NEW HAMPSHIRE: Several players from the first George W. Bush administration will not return to the second, and prominent among them is US Trade Representative Robert Zoellick. While instrumental in creating and at times maintaining the WTO Doha Round, Zoellick also left a troubling legacy. The many Free Trade Areas (FTAs) he negotiated promise to confound the global trade system and US long-term economic and foreign policy interests.

In the October 5 Wall Street Journal, Zoellick himself pointed to the issue, writing, "The Bush administration has completed FTAs with 12 countries, is negotiating with 10 others, and is preparing for more." That record perfectly reflects his commitment to FTAs as a tactic to achieve WTO progress – a lesson he absorbed from former Secretary of State Baker when GATT's Uruguay Round was foundering. But Zoellick over-learned the lesson; this time, US trade threats are less potent than those in the GATT years. In that respect, Zoellick's record recalls "The Sorcerer's Apprentice" – the helper who used magic to do his job but couldn't end the spell.

Like the helper's magical brooms, FTAs – in reality "preferential trade areas" – are madly multiplying, and do more harm than good. World-class economists like Jagdish Bhagwati regularly condemn them, as do a growing number of foreign policy specialists. Zoellick inadvertently revealed the reason in his Journal essay: "Integrating trade and foreign policy must be part of America's strategy." Yet his posture of proliferating FTAs has undermined not only US strategic and foreign policy interests, but other states' national interests, too. Australia's former ambassador to China calls them "an abomination," and Foreign Affairs editor James Hoge highlighted them in his essay, "A Global Power Shift in the Making": Southeast Asian states are steadily integrating their economies into a large web through trade and investment treaties. Unlike in the past, however, China – not Japan or the United States – is at the hub."

Former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense Kurt Campbell, in the Financial Times, sounded the same alarm: "Multilateral regional formations are proliferating with China rather than the US as the hub, sometimes without America even in attendance."

These developments are a product, however unintended, of America's FTA strategy. It has encouraged more of the same everywhere, most importantly in East Asia, the world's most dynamic economic region and the scene of a developing economic "community." Asia's intensifying economic ties, and increasing trade orientation toward China and away from the US, mean that Zoellick will leave a trade policy challenge greater than he inherited.

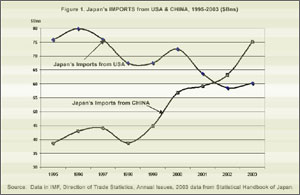

Three sets of data demonstrate Asia's new trade patterns. The first compares Japan's imports from the US and China, and uncovers a striking reversal of fortune. As recently as 1995, Japan's imports from the US were almost US$40 billion larger than those from China; last year, however, roughly US$15 billion more came from China.

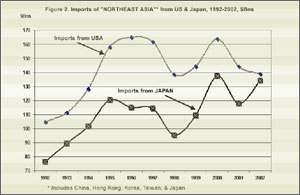

Northeast Asia (China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan) presents a second likely reversal of fortune. This is Asia's most vibrant economic sub-region, and a comparison of its imports from the US and Japan is revealing. In 1995, imports from the US totaled US$30 billion more than those from Japan, but in 2002, the two were almost identical. The 2003 data will probably show Japan ahead.

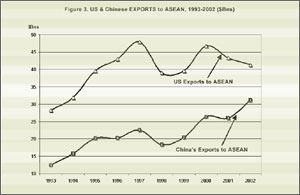

US and Chinese exports to ASEAN, now an important market for both, demonstrate similar trends. US officials expect exports to ASEAN to reach US$50 billion this year – an impressive figure, but less so when compared with China's record. Between 1993 and 2002, US exports to ASEAN rose 46 percent, from US$28 billion to US$45 billion. Meanwhile, China's grew from US$12 billion to more than US$31 billion – a 150 percent increase. Spanning the period surrounding the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis, the data show how differently the crisis affected American and Chinese trade with ASEAN. After 2000, China's exports resumed their upward movement, though America's did not.

Additional troubling evidence emerges when recent US and Chinese imports from ASEAN's largest economies are compared. From 2001 to 2003, Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore each doubled their China exports (to US$14 billion, US$9 billion, and US$10 billion, respectively).

These new trade patterns are the background to today's revival of earlier proposals for an Asian economic community. In past years, the concept had little rationale in the region's economy: It lacked a heavyweight other than Japan, which was not much interested, and its interactions were mainly with the US. Today, an "East Asian Economic Community," whether by that name or some other, is being actively pressed not only by relatively small states, but also by China, Korea, and in different ways, Japan.

In 2002, China and ASEAN began talks on a free trade accord, and China soon called for a "China-ASEAN" free trade area within 10 years. Beijing continues to prod, as in some "early harvest" tariff-reduction steps, and last month saw agreements for further gradual reductions. They included large exceptions for ASEAN's "sensitive sectors," but the process, under China's impetus, is underway. Indeed, Beijing recently proposed a step that a generation ago would have struck cold fear into Asia's other capitals: It exhorted representatives of Asia's 20 million "overseas Chinese" to "play a positive role in enhancing the good neighborly friendship and political trust between China and…ASEAN."

This year has seen other previously unthinkable cooperative steps, including talks among all 13 Asian Foreign and Finance Ministers to create an Asian Bond Market.

These developments, which reflect and promote a regionalized world, will not initially be affected by Mr. Bush's re-election. But Zoellick's departure and former US National Security Council director Brent Scowcroft's comments – that the President's second term foreign policies will differ significantly from the first – suggest a trade policy shift. Returning the WTO to center stage is a good prospect for several reasons, among them pressures to reduce trade tensions with the EU and recognition that trade gains from the many proposed FTA's are marginal at best.

Above all is the need to revitalize the global trade system before it degenerates into a world of regional blocs – an anathema to America's global economic and strategic interests. Seventy years ago, the United States faced a world rapidly descending into regionalism, and its response was the Reciprocal Trade Act of 1934, which eventually became the GATT-WTO system. Since 1945, it has been integral to the revolution in trade, and the unquestionable economic growth it produced. Mr. Bush now has a similar opportunity to restart the global trade system, because both American and global interests make the regional alternative unacceptable.

1 James F. Hoge, Jr. "A Global Power Shift in the Making," Foreign Affairs, July-August 2004. My emphasis.

2 Kurt Campbell, "The US Turns its gaze from Asia at its peril," Financial Times, 22 June, 2004. My emphasis.

3 Unless stated otherwise, this and all following calculations are based on data in International Monetary Fund, Direction of Trade Statistics, Annual issues.

4 The region's imports from the US include those of Japan itself.

5 Japan too declined as ASEAN supplier, reinforcing Hoge's point about today's Asian trade: "China - not Japan or the United States - is at the hub."

6 "RI's exports to China rise slowly," The Jakarta Post, 21 July 2004

7 U.S. Commerce Department, U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services, Exhibit 13.

8 Xinhua, 16 July 2004. In a recent interview, a Chinese diplomat pointed to the Nanyang community as one of three factors leading to Beijing's ASEAN free trade initiative.

9 See, for example, "Asian Foreign Ministers Support Local Currency Regional Bond market," Xinhua 21 June, 2004, and similar reports from Seoul in May, 2004.

10 From the keynote speech of the new Malaysian Premier at the annual conference of the Nikkei newspapers, reported on 3 June 2004 in Bernama (Kuala Lumpur).

11 Financial Times, 5 August 2004. "China, Japan, and Malaysia back fresh move to create 'East Asian community'."

12 Former Ambassador to the US and UN Tommy Koh's speech at the conclusion of the China-Japan Asian Cup finals, 11 August 2004.

Bernard K. Gordon is the author most recently of Trade Follies: Turning Economic Leadership into Strategic Weakness (Routledge, 2001), and “A High-Risk Trade Policy,” Foreign Affairs, Summer, 2003. He is Professor Emeritus at the University of New Hampshire.