US Voters Mull the Economy

US Voters Mull the Economy

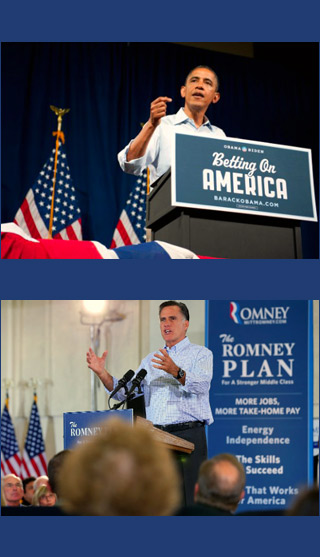

WASHINGTON: In 1992, Bill Clinton won the US presidency largely on the strength of a simple campaign message: “It’s the economy, stupid!” Two decades later, in another election, the winning slogan might well be, “It’s the economy again, stupid!”

Public opinion surveys show that economic issues are a foremost concern for American voters. Recent history suggests that voters’ choice on November 6 will have implications not just for the economic health of the United States but also the global economy.

In the run-up to the 2012 election, the US economy is still struggling to recover from the Great Recession. The real gross domestic product grew an anemic 1.7 percent in the second quarter of 2012; the unemployment rate was 8.3 percent in July.

Four in five Americans are unsatisfied with the way things are going in the country, according to a June Gallup survey. Most blame the economy. A July Pew Research Center poll found 33 percent of voters citing jobs as their top concern in deciding their vote, with an additional 19 percent mentioning the budget deficit.

But voters are conflicted over what the the next president should do about these concerns. There’s strong public resistance to cuts in government-funded entitlement programs – such as Social Security, the national pension scheme, or Medicare, the national health insurance program for the elderly. And 51 percent of Americans say that maintaining benefits is more important than deficit reduction.

The public supports a combination of budget cuts and tax increases, especially on the wealthy. By two to one, 44 to 22 percent, Americans expect that raising taxes on incomes above $250,000 would help the US economy rather than hurt it, according to the Pew Research Center survey.

Thus, the US president in 2013 faces a conundrum. The voters want the economy fixed, but resist, or are divided at best, on the sacrifices required for achieving a solution. The presidential election is likely to turn on how voters assess implications of the economic platforms of the two candidates.

As the incumbent, Barack Obama has articulated more specific economic plans, if only because he must present annual budgets to Congress. In his 2013 budget request, Obama proposed increasing government outlays by 19 percent by 2017. He would cut national defense spending from 4.6 percent of GDP to 2.9 percent by 2017. If reelected, he also plans to cut the annual federal budget deficit from 8.5 percent in 2012 to 3 percent by 2017.

Obama has called for continuing current tax rates for 98 percent of the American public earning less than $250,000 and advocates raising tax rates from 35 to 39 percent for those making more than that amount.

On trade issues, Obama has pledged to complete the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free trade agreement with at least nine Pacific rim nations, and in December will decide on whether to pursue a free trade agreement with Europe. He has increased trade enforcement.

As challenger, Romney’s tax and spending proposals are less specific. He has promised to cut federal government spending by $500 billion per year by 2016 and hold such outlays to less than 20 percent of GDP, down from the current 24 percent. His proposed tax cuts would reduce revenues by $3.4 trillion over the next decade, which he claims will be made up by faster growth and a broader tax base.

Romney’s budget proposal would increase US defense spending to 4 percent of GDP, adding $2.1 trillion to military outlays over the next 10 years. He promises to cut US foreign aid, which totaled $30.7 billion in 2011, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. He has said he would not help bail out European Union banks if they get into trouble because of the euro crisis.

On trade issues, Romney also pledges to finish the TPP and more explicitly suggests pursuit of a free trade agreement with Europe. Potentially most significant is his vow to cite China for currency manipulation, which could trigger a trade war, dragging in the many countries in China’s supply chain.

Foreigners’ stake in the economic choices confronting the American voter could not be greater.

Candidate Romney has espoused fiscal austerity at home, while criticizing fiscal profligacy abroad. The former Massachusetts governor has frequently chastised European governments, in particular, for failure to hold down public spending.

Obama’s approach to government spending is driven by belief in the economic efficacy of public outlays as a means of pump priming the economy. His budgets also provide a longer glide path in reduced government spending.

Romney has proposed a cut in the highest marginal US income tax rate from 35 to 28 percent – the wealthiest US taxpayers would then pay a lower federal income tax rate than that imposed in 25 of 33 OECD countries, possibly leading some foreign entrepreneurs to see the United States as a better place to make their fortunes. Moreover, his proposed cut of the 35 percent US corporate tax rate to 25 percent would move the US from having the highest corporate rate among the major economies to a rate near the OECD average of 23 percent, again possibly making the United States a more competitive home for corporations.

Obama too has proposed reducing the US corporate tax rate to 28 percent, but advocates raising the top marginal income tax rate to 39 percent, the rate in the late 1990s, arguing that such a rate in no way hampered US competitiveness. At this rate, the wealthy would still pay a lower tax than those in 15 other OECD countries.

These spending and taxing policies have serious implications for the US budget deficit and government debt.

The US government debt held by the public is of particular interest to the world, because a larger debt is likely to drain much-needed capital from other economies to fund the American imbalance; it could slow both US and world growth, and might heighten the risk of renewed financial turmoil.

The 2013 Obama budget proposal claims that the deficit will fall to 3 percent under his watch by 2017. Romney has set no specific short-term budgetary target, but said he’ll balance the budget by 2020.

The Obama budget forecasts a US debt to GDP ratio of 77.1 percent by 2017. The Romney campaign has not released enough details about its economic plans to provide an estimated impact on government debt.

Beyond budgetary and debt policy, as the world’s largest importer and second largest exporter, future US trade policy also has international economic implications. Both Romney and Obama have promised to increase trade, while being tough on those nations that allegedly practice unfair trade.

While 67 percent of Americans report that international trade and business ties are good for the US economy, this is the lowest support among the 21 nations surveyed by the Pew Research Center in 2011. In addition, surveys show that Americans believe trade kills jobs, undermines wages and doesn’t necessarily reduce prices.

This lack of faith in trade by the American public may mean that the next president, regardless of trade-promotion intentions in Europe and Asia, may receive tepid support for such initiatives.

The outcome of the presidential election is likely to turn on economic issues. Whoever the winner, he promises a leaner, healthier economy. If he succeeds, other countries will face a rejuvenated competitor. If he fails, the resultant slower American growth and growing debt burden could hobble global economic recovery for years to come.

Bruce Stokes is director of Global Economic Attitudes at the Pew Research Center in Washington.