Venezuela Is Not a Big Priority for Russia, China or Iran

Venezuela Is Not a Big Priority for Russia, China or Iran

NEW YORK: Since the election of Hugo Chávez Frias to the Venezuelan presidency in 1998, followed by Nicolás Maduro in 2013, Venezuela has endured steady decline with the approval of the new constitution in 1999, concentration of presidential power, the capture of state and private institutions, gradual control over the press, mismanagement of its national oil company and establishment of a failed political project known as the “socialism of the 21st century.”

With 81.8 percent of Venezuelan households in poverty, 1.5 million of its citizens leaving the country, 78 percent of medical centers suffering from a supply of medications, an inflation rate that may pass 2,300 percent in 2018, oil revenues cut by half and shortages of gasoline, Chávez and Maduro literally ruined the country.

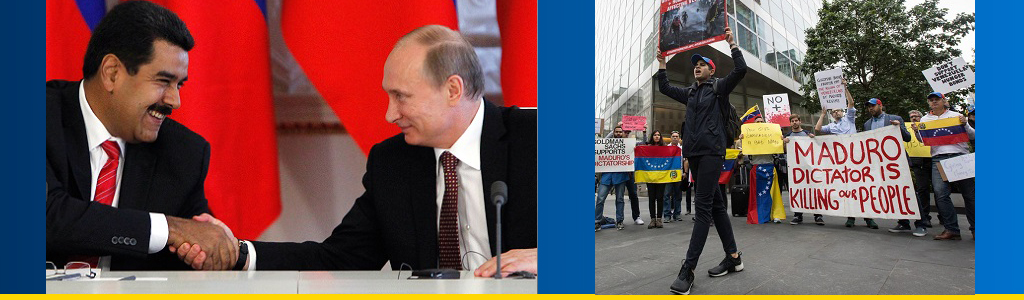

These economic challenges have influenced foreign relations. Alliances sought to counter the United States are starting to backfire. The official line is that the government is strengthening strategic relations with partners like Moscow and Beijing as well as Tehran. But the Maduro administration has exaggerated the strength of those ties.

The priority is not helping Venezuela but countering US hegemony in regional politics. For example, Russia and China did not attend an informal November meeting of the UN Security Council that sought to condemn Venezuela for human rights violations and undermining the country’s constitutional order. Vassily Nebenzia, Russia’s permanent representative to the UN, stood alongside Venezuelan counterpart Rafael Ramirez who denounced Washington for a "crusade" against Caracas.

Russia and China help bankroll Venezuela, but a Bulltick Capital report suggests a 90 percent probability that Venezuela will struggle to repay its debts and other financial obligations this year – a problem for both countries that have lent Venezuela billions of dollars and paid for oil in advance. Rosneft sent $6 billion to its Venezuelan equivalent, PDVSA, in early 2017 and announced in August it planned no more advance payments. Russia gave Venezuela a brief break in November by agreeing to restructure about $3 billion in loans, buying Maduro time to pay off other creditors and assure bondholders. After helping Venezuela three times in 2017, Russia might be running out of patience. Nevertheless, Moscow’s loans to the Venezuelan government form part of a strategy that uses Rosneft to achieve foreign policy objectives.

In fact, Russia behaves like a predatory lender when it comes to Caracas. The newspaper El Nacional reported in October that Moscow and Beijing took over refineries in Paraguana, “renting” them. The move is controversial, violating the 2006 Law of Organic Hydrocarbons, ironically a Chávez instrument. Venezuelan law indicates that only national firms registered in the National Registry of Contractors can work for the state.

.png)

Trade with Russia has increased since 2005, and a joint venture to export flowers began in 2006. But Moscow did not need Venezuelan oil and commerce with Brazil carried higher priority. By 2008, the large asymmetry in trade imbalances emerged between the two countries: Venezuela imported $967.4 million, mostly military purchases, while exporting $320,000 dollars in goods to Russia. After 2006 when the United States refused to sell American military technology to Caracas, Russia became primary provider with sales based on credit, either from Russian banks or the government.

Moscow maintains military relations with Caracas mostly for geopolitical, propaganda and symbolic reasons. Venezuela supported the 2008 Russian incursion into Georgia and invited the Russian nuclear warship Peter the Great to conduct joint exercises in the Caribbean, essentially the US backyard. In 2016 at the United Nations, Venezuela voted to support Russia against a resolution for a ceasefire in Aleppo. In February 2017, Venezuelan Foreign Minister Delcy Rodriguez described Russia as a global actor that supports global stability and lauded Moscow’s role in confronting international challenges. In turn, Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov declared that Russian-Venezuelan relations were “booming,” and a few months later an agreement was revealed – Russia would supply Venezuela with 60,000 tons of wheat per month, although the same could be obtained at lower cost from Argentina.

Venezuela has tried to diversify its benefactors and reduce dependence on the American oil market. The 2001 visit of Jiang Zemin, the first of a Chinese president to Venezuela, and of Chávez to Beijing in 2002 marked the start of a diplomatic pivot for Caracas in Asia. Chinese commerce with Venezuela has grown exponentially since. In 2014 China became the nation’s second largest trading partner with more than $15.7 billion in trade. China has since replaced Russia, long considered Venezuela’s key military ally, as its major supplier of armament and defense technology. China offers more advanced technologies and provides better service in terms of maintenance and replacement parts. At the same time, Venezuela has opposed condemnations against China for human rights violations and supported Beijing in the search for global use of alternatives to the dollar.

Although China has lent Venezuela more than $60 billion, it recently suspended further loans to Caracas. Chinese Sinopec, the oil and gas conglomerate, sued Venezuela’s national oil company PDVSA in December because it did not receive full payments for its orders. Chinese companies are also reported to have lost interest in investing in Venezuela due to the high levels of corruption.

Venezuela also has ties with Iran. Iranian revolutionary ideology in the 1980s was influenced by Latin American leftist doctrine and the two countries constructed consensus around an "anti-imperialist" axis. Since 2001, both countries have reached more than 340 agreements in technology, health, industry, infrastructure, culture, defense and housing. Nevertheless, the vast majority of these agreements have not been implemented. A 2006 joint venture between former Chávez and Iran’s former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to build cars through Venirauto Industrias C.A. generated losses and was largely unsuccessful. Another joint venture to produce corn flour struggled with low productivity despite high demand for the product in Venezuela. By 2014, Iran canceled a project of the Persian Gulf Petrochemicals Holding in Venezuela. Iran’s Rokneddin Javadi, former deputy oil minister of Iran, admitted that establishing offices of the National Iranian Oil Company in Venezuela had no economic justification but rather served political purposes.

In return, Venezuela was one of the few nations to oppose the International Atomic Energy Agency’s efforts to present the Iranian nuclear program case to the UN Security Council in 2006. Venezuela supported Iran in criticizing Israel, and in January that year broke off diplomatic relations in response to the Israeli offensive in Gaza. In November 2007 at OPEC’s third summit, Chávez tried to persuade members to transform into a more active geopolitical group that supported Iran. Saudi Arabia opposed that proposal.

A military relationship between Iran and Venezuela is in question. Some have accused Iran of installing intermediate missile systems in the country, though General Douglas Fraser, former head of the US Southern Command, dismissed an Iranian military presence in Venezuela. Nevertheless, some officials like Vice President Tareck el Aissami are reported to have provided assistance to Iran and Hezbollah. In 2013, state-owned Venezuelan weapons company CAVIM was sanctioned for trade with Iran. Under Chávez in 2008, trade between both nations was approximately $57 million with additional investments.

For Iran, China and Russia, Venezuela is a small and distant priority. The country’s value is for needling the United States, much less necessary with the distractions and “America first” policies endorsed by Donald Trump. Venezuela’s chaotic economic crisis is more pressing as its relationship with Russia, Iran and China weaken. The imbalanced relationships ensure that Venezuela is but a pawn for legitimizing those countries' policies on the world stage rather than advancing a real agenda of its own.

Carlo J.V. Caro is a graduate student in US Foreign Relations at Columbia University. He has published commentary for Foreign Affairs, Forbes, the National Interest and HuffPost.

Comments

None of this would have happened if from 1990 our policy was other than to destroy Russia and treat China as the British did in times past.