Vietnam – Globalized Party-State

Vietnam – Globalized Party-State

STOCKHOLM: For US President Donald Trump, his second summit with North Korea’s Kim Jong-un was reality check rather than success. For host Vietnam, though, the summit was undoubtedly a grand triumph. The country’s rapid economic development and deft diplomacy gained unprecedented spotlight while a recent cybersecurity law and detentions of regime critics went unnoticed.

Vietnam accomplished a lot with Trump. Meeting with President and Party Secretary Nguyễn Phú Trong, Trump said that he “felt very good about having this summit in Vietnam because you really are an example of what can happen with good thinking.” He added that Vietnam is “thriving like few places on earth” and emerging as a model for North Korea. The two men oversaw the signing of $20 billion in commercial trade deals.

Good ties with the US also enhance Vietnam’s security situation. China’s growing strength is making it increasingly important for Hanoi to hedge, and the United States is the natural counterweight – despite the devastating Vietnam War ending in 1975, during which more than 2 1/2 million US soldiers served in the country in the effort to prevent communism spreading beyond North Vietnam.

Vietnam has clawed its way toward more capitalism and a market system despite communist rule. The country remains a party-state, with the leading role of the Communist Party written into the Constitution, which also states that it is the duty of the Vietnamese armed forces to defend not only the country but also the party. Two seemingly incompatible images emerge, one of a country increasingly integrated into the global economy and one of a party determined to maintain its monopoly on power in an era when social media is an integral part of everyday life.

The median age in Vietnam is 31, so its younger generation has only heard about struggles during and after the war. The decade immediately after the war was much more difficult for Vietnam than foreseen. The country’s reunification was based on the North Vietnamese model, more than 2 million people left the country, many as boat refugees and many of Chinese ethnic origin. Hanoi entered into a friendship treaty with the Soviet Union, straining Sino-Vietnamese relations, and after a period of border confrontations, Vietnamese troops in December 1978 entered Pot Pot’s Cambodia and removed the regime. Deng Xiaoping’s China, wanting to teach Hanoi a lesson, launched a costly attack on Vietnam’s northern border regions in 1979. China mobilized more than 600,000 troops, with 200,000 going into Vietnam. Relations remained frozen for more than a decade. The United States, China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations formed an unholy alliance in support of Cambodia’s Prince Sihanouk and the Khmer Rouge – and Vietnam found itself isolated and barely able to feed itself.

The year 1986 became a turning point with the launching of Vietnam’s doi moi renovation process. The government de-collectivized agriculture, created space for private initiatives, and opened the economy for trade and foreign direct investment. A huge rice deficit quickly turned into a surplus, and Vietnam soon became the third largest rice exporter in the world. In a letter in 1995 to his Politburo colleagues, Prime Minister Võ Văn Kiệt told them not to fear the future. Nguyễn Co Thach, the legendary foreign minister, described 1995 as a bumper crop year. Vietnam normalized relations with the US; entered an agreement with the EU; and became a member of ASEAN, an organization originally formed in 1967 to contain Vietnam and communism.

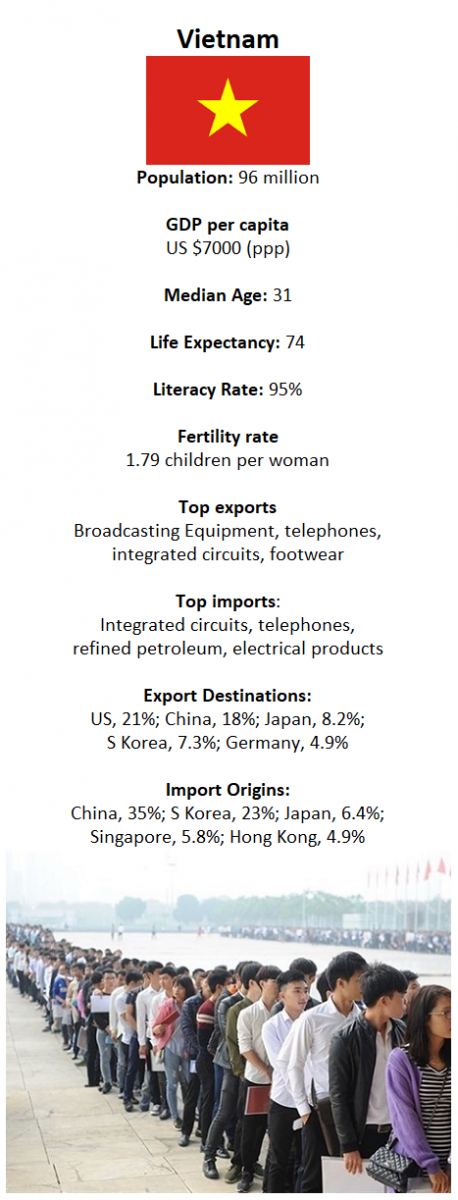

The past 25 years have been a period of economic and social momentum. The country’s foreign policy has been successful, creating a conducive international environment, with an economy growing by about 7 percent a year. Social indicators also tell an impressive story. The share of the population living below the poverty line has fallen from above 50 percent in 1992 to 3 percent today, with income inequality increasing without reaching extreme levels.

The role of foreign trade has grown dramatically, the total value of the country’s foreign trade today being twice as large as its GDP, with foreign direct investment as a major factor. In 2018, the volume of new FDI commitments equaled 8 percent of GDP. Seafood, crude oil, coffee and rice are big export items, but are not enough to power the economic growth. South Korea’s Samsung investments are in a class of its own. Millions of smartphones are assembled at its plant in Thai Nguyen, north of Hanoi, and that one with other Samsung factories employ more than 150,000 workers. Exports from Samsung’s factories generate close to one fourth of Vietnam’s total export earnings, more than US$50 billion in 2018.

The dilemma is that the value added from foreign direct investments, mainly labor, remains low, and linkages to the domestic economy remain rather weak. Vietnam is at the lower spectrum of the value chain. FDI receives priority while reforms of state-owned enterprises remain slow and small- and medium-sized enterprises still do not receive sufficient recognition. Large conglomerates like Vingroup with oligarch Phạm Nhật Vượng are more welcome, and interesting startups are entering the scene, but the current model does not offer sufficient space for truly dynamic domestic development.

Two factors are crucial, the quality of higher education and the Communist Party’s attitude. Attracting FDI is considered more manageable than actively promoting small- and medium-sized enterprises, with potential political implications.

In 2007, Vietnam joined the World Trade Organization. As ASEAN member, Vietnam is part of trade agreements with Japan, China and South Korea and, in recent years, negotiated a number of major free trade agreements, including a bilateral agreement with South Korea in 2015 and the Transpacific Partnership Agreement, TPP, organized by former US President Barack Obama. Obama went out of his way to include Vietnam, inviting Party Secretary Trong to the White House in 2015. Trump ditched the agreement, but the other 11 countries persevered, and a Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement on Transpacific Partnership, CPTPP, has now entered into force. Vietnam and the European Union also finalized an agreement in 2015, but it has not yet been approved by the European Parliament as some members expressed concerns about human rights. Both agreements include potentially important articles about labor rights and, in the EU-Vietnam agreement, a paragraph about civil society’s monitoring role suggesting that new space should be opening for labor.

Such international economic development stands in stark contrast to the political frontier, where the party shows little willingness to give up its monopoly on power. Party Secretary Trong, who also chairs the military commission and last year become president of Vietnam, is a party builder rather than a reformist, focused on strengthening party legitimacy by fighting corruption. A former Politburo member and oligarchs have received long prison sentences. Still, Transparency International’s ranking of Vietnam has fallen further, the country ranked 117 out of 180 nations in 2018, demonstrating the limitations of party-driven anti-corruption campaign in lieu of systemic reforms.

In mid-2018, the government exposed its ambitions to control social media with introduction of a cyber law that led to widespread protests. In January, a slightly modified version became law. Vietnam, in sharp contrast to China, allows Facebook and Google. The new law requires Facebook to censor anti-government content among its 38 million Facebook users, 40 percent of the entire population, and allow authorities to access users’ online data. The genie, however, is already out of the bottle. The party risks deepening its image of belonging to the past rather than the future.

So far, the party has managed its unorthodox path to a market economy, but could soon face tough choices. Vietnam’s big challenge is to venture choosing a more open way forward than China, ultimately daring to move beyond the party-state and realizing Vietnam’s huge potential.

Börje Ljunggren is former Swedish Ambassador to Vietnam and China, author of Den kinesiska drömmen –Xi, makten och utmaningarna/The Chinese Dream – Xi, Power and Challenges (2017) and co-editor of a forthcoming volume on contemporary Vietnam.

Correction: The arrest photo unrelated to this article misidentified the charge.

Comments

While Ambassador Börje Ljunggren provides a fair enough assessment to today's Vietnam and its promising future, he's however mistaken "Vietnam's huge potential" requiring "to move beyond the party-state" and not because of the stability that the party state has been creating all along! How else Vietnam could unite its sovereignty and unleash the total population to be where they are, despite the French, American wars, the Khmer-Rouge and China's destructiveness with the West supports throughout the 1970-1990's? Even now, what Ambassador Börje Ljunggren calls "government critics" are mostly agitators and regime-changers with Western roots and Vietnam's social media is hijacked by over 4 millions anti-Vietnam fanatics, sheltering in Western countries! Vietnam can't afford the "correct" development model of the Philippines, Thailand nor risk the Western-sponsored "improvement" of Libya, Syria and already suffered through with the needlessness of Afghanistan, Iraq....