‘Wake Up and Face the Flat Earth’

'Wake Up and Face the Flat Earth'

Nayan Chanda:

Reading the book, one gets the impression that you took a dive into the innards of globalization and came out with some amazing tales of how things are happening behind the scenes that we don't see. What are, the main forces changing the globalized world today?

Thomas L. Friedman:

In doing this book, I didn't really read a bunch of other books, I really dove into the companies themselves who were spearheading this process. And the book, in that sense, is very inductive. I looked at what companies were doing and then tried to tease out the general patterns.

To begin with, my primary tutors for this book, were two Indian entrepreneurs: the president of Wipro, Vivec Paul, and the CEO of Infosys, Nandan Nilekani. So, how did I happen to end up with two Indian entrepreneurs? It's because they're actually at the epicenter of it now.

Secondly, I really dove into some key companies that are now globalizing and are really the source for understanding globalization. Wal-Mart, UPS – these are companies we don't traditionally think of as being goldmines of insights into globalization, but in fact if you understand what's going on inside these companies, you can get an amazing view of the flattening of the global playing field and the forces that are doing it.

Nayan Chanda:

Both these companies you mention do not produce anything. They agglomerate or repackage others' products. So how are they tapping the resources from this flat world?

Thomas L. Friedman:

Well, in the case of Wal-Mart, Wal-Mart's great innovation, as you say, is that Wal-Mart doesn't make anything. But what they do is draw products from all over the world and get them into stores at incredibly low prices. How do they do that? Through a global supply chain that has been designed down to the last atom of efficiency.

In the case of UPS, they've designed a global delivery system that allows them to deliver their products with that same efficiency; they literally have a phenomenon at UPS called "end-of-runway services." Right before your product gets shipped, they'll attach something: a new lens to your camera … a special logo to your tennis shoes. That's how efficient these systems have become.

Nayan Chanda:

Now of course, there have been a lot of criticisms of the business model of Wal-Mart, because it is driven by the single motive: maximizing profits for shareholders. And in the process, they give products at a cheap price to the consumers. But people are complaining that this model leaves the workers out of the equation. … So, is this a good model to promote?

Thomas L. Friedman:

Well, Wal-Mart to me, really demonstrates one of the phenomena of a flat world. I would call it "multiple-identity disorder." I have to tell you, the consumer in me loves Wal-Mart. Wow, you can go there and get really quality goods at really low prices. ... The shareholder in me loves Wal-Mart. The citizen in me hates Wal-Mart, because they only cover some 40 percent of their employees with health care ... and when a Wal-Mart employee that doesn't have health care gets sick, what do they do? They go to the emergency ward at general hospital, and … then we tax-payers pay their health care. The neighbor in me is very disturbed about Wal-Mart. Disturbed about stories about how they've discriminated against women, disturbed about stories that they've locked employees into their stores overnight, disturbed about how they pay some of their employees. So when it comes to Wal-Mart, Nayan, I've got multiple identity disorder, because the shareholder and the consumer in me feels one thing, and the citizen and the neighbor in me feel something quite different.

Nayan Chanda:

How do you resolve the dissonance you have between the citizen in you and the consumer in you?

Thomas L. Friedman:

I really support consumer activism that will say to Wal-Mart, that we as neighbors and consumers will say to Wal-Mart, "I love your low prices, but you know what? We're ready to spend five cents more … if you'll use two of those five cents to cover more of your employees with health care."

Nayan Chanda:

One of the few views that have come out of your book, the criticisms seem to be that in your flat world, the poorest of the countries, like Africa, don't really figure. So why are you leaving Africa behind in your discussion of the flat world?

Thomas L. Friedman:

I have a chapter in the book called "The Un-Flat World," in which I talk about the countries that are still the majority that still aren't flat. You know, the job of the analyst is really to identify a trend, just when it reaches the tipping point, but before anyone else sees it. And the trend is this flattening process, which I think has reached this tipping point, as evidenced by the degree that China and India – one-third of the planet – have been able to use and exploit this platform.

But I fully recognize that although it's reached the tipping point, there are still a lot of people who are not part of it. Africa is not part of it because it hasn't learned to globalize. Our job, as citizens of the planet, let alone as citizens of the wealthiest country in the world, is to help create the tools and conditions for places like Africa to be part of it.

Nayan Chanda:

Another point that becomes clear in your book is the role of the individual. And these individuals, who are either part of the flat world or outside of the flat world, are not geographically confined to one area. And at the same time, these people have political power, influence. How can these people's influence be not destructive?

Thomas L. Friedman:

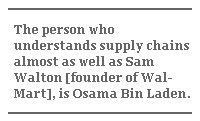

It's a problem actually. The flat world is a friend of Infosys and of Al-Qaeda. It's a friend of IBM and of Islamic jihad. Because these networks go both ways. And one thing we know about the bad guys: They're early adopters. Criminals, terrorists – very early adopters. The person who understands supply chains almost as well as Sam Walton [founder of Wal-Mart], is Osama Bin Laden. We have an issue there with the most frustrated and dangerous elements of the world using this flat planet in order to advance their goals. Our job is to try to soak up those tools, so that we can use these collaborative tools in a more constructive way.

Nayan Chanda:

Another element which is interesting compared to "Lexus and the Olive Tree," is that olive trees have not disappeared; olive trees still have strong roots. So how do nationalism and a flat world intersect?

Thomas L. Friedman:

You know in Lexus I wrote that no two countries would fight a war so long as they both had McDonald's. And I was really trying to give an example of how when a country gets a middle class big enough to sustain a McDonald's network, they generally want to focus on economic development.

In "Flat World," I take that theory one step further into what I call the "Dell Theory" – you know, Dell Computers. The Dell Theory says that no two countries that are part of the same global supply chain will ever fight a war as long as they're each still part of that supply chain.

Do I think this guarantees that there won't be a war? No, I understand olive trees; people will do crazy things over their olive trees. But here's what I predict: If you do go to war and you're part of one these supply-chains, whatever price you think you're going to pay, you're going to pay ten times more.

Nayan Chanda:

From the United States, it seems that the olive tree is simply turning away. There is barely a discussion in political circles or in media circles. How do you explain that, and what can one do about it?

Thomas L. Friedman:

I think there are four factors; it's a kind of "perfect storm" that's come together. ... First of all, there's 9/11, which completely distracted everyone – including myself – from this. Number two, there's the dot-com bust. A lot of very silly people equated globalization with the dot-com boom. And so when the bust came along, all these people said that globalization was over. Well, actually a flat world drove globalization to a whole new stratosphere. And the third factor is Enron. Enron made all CEOs guilty until proven innocent. As a result, people weren't interacting with them. Fourth is what's going on in the world of academia and basically the anti-globalization movement – which is basically dead today – because China and India have embraced this process and this project. I would argue that the anti-globalization movement and the people who have been its intellectual leaders, have been kind of dining out on the carcass of Globalization 2.0. And they're kind of like jackals that have been eating and picking away at this carcass all these years. They're all still talking about the IMF and the World Bank and conditionality – as if globalization is all about what the IMF and World Bank impose and force on the developing world. Well when the world is flat, there's a lot more globalization that's about pull. This is people in the developing world – in China, Russia, India, Brazil – wanting to pull down these opportunities.

So for all these reasons, right when we've reach this incredible inflection point – the world is getting flat, which I believe this is the equivalent of Gutenberg and the printing press – nobody is talking about it.

Click here for the full transcript.

Click here for the video of the interview.