War of Words: What’s in the Name “Rohingya”?

War of Words: What's in the Name “Rohingya”?

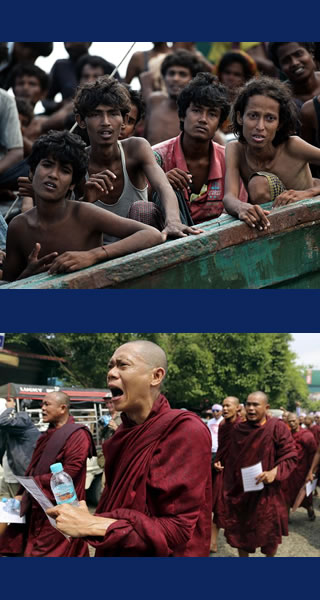

OXFORD: The government in Myanmar, trying to rewrite history in defining its identity, is engaging in ethnic cleansing. The target are the Rohingya, a people the United Nations and Amnesty International call “the most persecuted refugees in the world.”

Myanmar is home to a large and diverse number of ethnic and religious groups: 135 ethnic groups officially recognized by the current constitution of Myanmar plus the Rohingya, the only Muslims, who are excluded. For nationalist extremists, the Rohingya are not an independent ethnic group with ties to the land in the state of Arakan where they live. Instead, the nationalists insist the Rohingya migrated to Arakan after Burma was progressively absorbed into British India from 1824 onwards. The nationalists view Rohingya as an illegitimate colonial import, not in keeping with the Buddhist Tibeto-Burman character, and refer to them as “Bengalis.”

The US Embassy in Myanmar refuses to go along. On April 19, a boat carrying a number of Rohingya capsized and 40 people drowned. The group was trying to reach a nearby town with a hospital, a market and access to other services severely restricted inside the camps for internally displaced persons, where some 140,000 Rohingya live after four years of sporadic inter-communal violence.

In issuing a statement of condolences to the families of the victims, the US embassy referred to the dead as “Rohingya.” The nationalists find that name more threatening than direct criticism of the “apartheid-like” conditions which these people endure. To a Western reader, this may seem odd. Surely an accusation that a state and many of its people engage in ethnic cleansing bordering on genocide should be vehemently denied. But this is how far the situation has gone in Myanmar: The perpetrators of the oppression against the Rohingya – extremist nationalists and Buddhist monks aided and abated by many elements of the police, military and border agency – fully acknowledge the violence and indeed, think it is justified.

The humanitarian crisis in Myanmar bubbles to the surface a few times every year and then tends to be forgotten once the 24-hour news cycle moves on to the next calamity. What lingers is “direct state complicity in ethnic cleansing and severe human rights abuses, blocking of humanitarian aid and incitement of anti-Muslim violence, constituting ominous warning signs of genocide,” as described by United to End Genocide, a non-profit in Washington headed by former US Congressman Tom Andrews.

At the core is the way in which the country has sought to define its national identity after gaining independence from Britain in 1948. Upon independence, Myanmar became a multi-party parliamentary democracy. But that did not last. The borders of the state were defined by convention on the borders of the pre-colonial Burmese empire of King Bodawpaya, prior to the first Anglo-Burmese War (1824-1826). The conflicts between some of these groups and the central government led to the military takeover of the government from 1962 effectively until last year. Even now, the military establishment retains veto powers over the new civilian government.

Throughout this period of military administration, the central government has worked at building a nation out of the many ethnic groups in terms of religion, Theravada Buddhism, and race, fair-skinned Tibeto-Burman. The Rohingya are dark-skinned, South Asian Muslims. And so, they have been regarded as the definitive enemy within and “threat to the national purity” of the country for all these decades.

The nationalists support removing the aliens from Myanmar for deportation to Bangladesh. Never mind universal human rights and international law that prohibits denial of citizenship – rendering those born in a nation’s territory stateless – or any suggestion that after two centuries a people might claim a right to land.

The United States and the international community recognize that “communities anywhere have the ability to decide what they should be called,” insists US Ambassador Scot Marciel. “And normally when that happens we would call them what they want to be called. It’s not a political decision; it’s just a normal practice.” Myanmar’s new de facto leader, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, rebuked the US ambassador for such high-mindedness and sides with the nationalists.

The word “Rohingya” wields power because it carries the torch of historical truth that dissolves the impossibly contrived case for ethnic cleansing, linking the Rohingya with the British Raj. This is why those who would carry out ethnic cleansing in Myanmar fear it.

The nationalists’ narrative is historically baseless. The state of Arakan has not traditionally been part of the Burmese political and cultural space. The emperor King Bodawpaya annexed Arakan in 1785, just 39 years before the nationalists’ 1824 cut-off point for their “legitimate history.” Arakan had been annexed by precursor Burmese empires, but was not held for extensive periods over the previous thousand years.

Between the state of Arakan and the Burmese heartlands in the basin of the Irrawaddy River there is a difficult-to-traverse mountain range whereas the Arakan coast is neatly on the Bay of Bengal. The area is a natural geographic extension of the Bengali political and cultural space, not the Burmese one. Ethnic and cultural affinities with the people of the Bengal are not surprising. And it is historically documented that the Burmese Rakhine ethnic group, from which most of the extremist elements are drawn, only arrived in the area around 1000 AD.

But the most important reason for giving no ground to the extremists’ revisionist history is that the word “Rohingya” is historically documented in the region prior to the British Raj. Muslims have lived in the region from the 7th century, alongside Hindus and Buddhists, according to an assessment by U.K. Min. Before 1824, the British referred to the region as Rohang and those who lived there as Rohingyas. Later reports from the 19th century, including the 1852 Account of the Burman Empire, Compiled from the Works of Colonel Symes, Major Canning, Captain Cox, Dr. Leyden, Dr. Buchanan, Calcutta, D'Rozario and Co, refer to how the local Muslims called themselves “Rovingaw” or “Rooinga.” Likewise, a 1799 study of languages spoken in the Burmese area divides the natives of Arakan state between Yakain and Rooinga.

The Classical Journal of 1811 has a comparative list of numbers in many East and Central Asian languages, identifying three spoken in the “Burmah Empire,” and distinguishes between the Rohingya and the Rakhine as the main ethnic groups in the region. Likewise, Rooinga is structurally different to Bengali. A German compendium of languages of the wider region once again mentions the existence of the Rohingya as an ethnic group and separate language in 1815.

This is the history that the ethnic cleansers and their apologists are trying to obscure. They claim that the “Bengalis” invented the term “Rohingya” to hide an illegitimate Bengali background. And this is why the term “Rohingya” posits a threat for them. The word is in the history books – the same books showing that the area has been multi-ethnic and multi-confessional for well over a millennium.

The history books also show that Burma has been most successful as an open, inclusive and outward-looking country – a lesson that should be welcomed by the democratically elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi. And this is why the war over the word “Rohingya” must be fought, and won: The word looks to history but also charts a path for Myanmar with a future that’s every bit the glorious, peaceful, creative and open country that it once was.

Dr. Azeem Ibrahim is a fellow at Mansfield College University of Oxford and author of The Rohingyas: Inside Myanmar’s Hidden Genocide (Hurst Publishers, distributed by Oxford University Press)

Comments

It's a shame that the only factions doing deep historical research on the Rohingya topic are the current and former factions/ethnicities to the dispute:

* pro-Rohingya scholars who are fellow Muslims,

* opposing scholars from"

** opposing factions in Myanmar, and

** from some Buddhists worldwide, and

** from the anti-Muslim world (e.g.: India, Israel, etc.), and

* Myanmar's former colonizers (the British).

This is an issue that cries out for truly independent, neutral observers and scholars, and truly objective research -- like from Latin-American Scholars, or North American scholars, or Continental European scholars, or Japanese* / Australian / NewZealander scholars -- NOT related to, nor allied with, any of the conflict factions, and not under any government control.

(* no: Oft-cited scholar Aye Chan is IN Japan, but is a Rhakine from Myanmar, co-founder of a Rakhine nationalist group, the WAO)

But, then, who among us would care enough to truly investigate these obscure, powerless, alien people?

Sadly, it remains so:

In war, Truth is the first casualty;

...and...

History is written by the victors.

...and...

Only the losers are executed for war crimes.

While trying to hail Burma as an open and inclusive society for centuries and attempting to condemn Burmese Buddhists and nationalists at the same time, the author conveniently skips some of the most inconvenient truths himself. Focusing so much on whether the word 'Rohingya' existed or not in some form or another prior to the independence of Burma would not deny the fact that they were basically Arakanese Muslims and referred to as such umpteen number of times in official reports and Rohingya was only one of the Muslim ethnicities in the region.

How does this justify the fact that Rohingyas have waged terrorism against the state of Burma and Buddhists since the second world war in a bid to create an Islamic nation? The author nowhere mentions the fact that a large number of Indian Muslims migrated to Burma during British rule in which Burma was treated as a part of India and the migration was initially meant to fulfill the need for small-time workers in Burma but they started taking Burmese women as wives but only later to discard them as per their wishes stating that as per Islamic law they were not even their legal wives. This created feelings of unrest in Burmese Buddhists and later Zerbadee marriage was defined as a marriage between an Indian Muslim man and Burmese Buddhist woman and specific terms were laid out about their conversion to Islam or lack of it. Slowly, these Muslims took over native Burmese Muslims in numbers and started their expansionist agenda, converting Buddhist women to islam by marriage and treating those who did not convert as slaves. Naturally, this attracted violent reaction from Burmese Buddhists and infighting between Muslims in Burma and Burmese Buddhists continued.

In the Second World War, British saw that Burmese Buddhists were planning to take help of Japanese to get rid of British occupation. They used Muslims against Burmese Buddhists and asked them to fight against Japanese and in turn British would help them establish an islamic nation. It is interesting to note that how easily and quickly Arakanese Muslims came to accept this offer to divide their nation for sake of Islam. Their lack of patriotism has been at the core of this Rohingya problem. Several jihadi groups were constituted by Muslims to fight against Burmese Buddhists and 'holy war' was waged against Burma for an Islamic nation.

Nowhere does this article points out that so-called Rohingyas wanted to join East Pakistan in 1947 and an year prior to that many Muslim religious leaders called them to jihad against Buddhists to join islamic nation of Pakistan which was going to be formed. They killed and tortured Buddhists and in turn they were killed and tortured by Buddhists who wanted to save their nation. Even after British left and Burma gained independence in 1948, Rohingyas continued to fight for this elusive islamic nation. In 1971, when East Pakistan became Bangladesh, Rohingyas wanted to join this new islamic nation but their plans were foiled once again, not to mention the level of bloodshed caused. In recent decades, there have been terrorist groups in Bangladesh as well which have been arming Rohingyas and providing them with help to keep fighting for islamic nation and this is why Rohingya problem has resurfaced its ugly head. They never were fighting against persecution and not are, its only mainstream media and islamic apologists like this author who seek to portray them as persecuted. The agenda of Rohingyas is to create a new islamic nation which. For obvious reasons, Burma is entitled to oppose with brute force, let anyone call it persecution if they want. The truth is that today Rohingyas have support from global terror networks to spread Islamic terror. They have now only grown from a regional threat to a global threat and this is why Islamic apologist media, pseudo liberal and apologist politicians and intellectuals on payrolls of Islamic organizations are spreading the propaganda of Rohingya persecution while suppressing details of Rohingya terrorism and their atrocities.