Water Challenges Asia’s Rising Powers – Part I

Water Challenges Asia’s Rising Powers – Part I

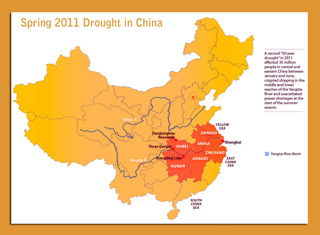

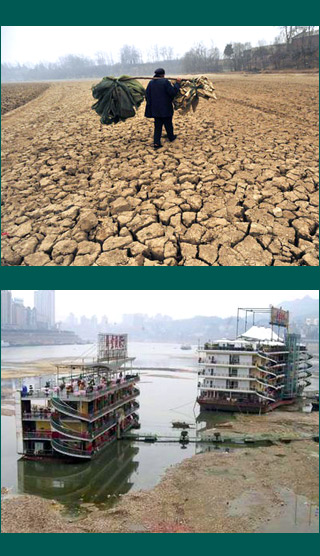

BEIJING: Before heavy June rains ended one of the most severe droughts in the Yangtze River Basin in 60 years, farmers in Hubei Province warned of rice shortages because of late planting. Downriver, coal-fired power plants cut back electrical generation because coal-loaded barges couldn’t navigate the low waters. The Yangtze’s shallow depth and the utility industry’s weakened power output reflect both this spring’s unusual conditions and the growing resource confrontation China faces with water, energy and food.

The drought put pressure on energy and food prices, influenced the rise in commodity prices in global markets for grain and equipment, and added to central government worries about inflation. And this occurred in southern China, the region that holds 80 percent of the nation’s freshwater supply.

Meanwhile a second persistent drought has gripped China’s dry north, which produces most of the nation’s energy and much of its grain, yet holds just 20 percent of China’s freshwater reserves. The scarce rainfall has prompted cutbacks in water allotments to farmers, reduced coal and power production, and accelerated water conservation and recycling programs.

“Water shortage is the most important challenge to China right now,” said Wang Yahua, deputy director of the Center for China Study at Tsinghua University in Beijing. “It’s a puzzle that the country has to solve.”

By almost any measure, conventional and otherwise, China’s tireless advance to international economic prominence has been nothing less than astonishing. Over the last decade alone, 70 million new jobs emerged from an economy that in 2010, according to the World Bank and other authorities, generated the world’s largest markets for cars, steel, cement, glass, housing, energy, power plants, wind turbines, solar panels, high-speed rail systems and other basic equipment to support a modern economy.

Yet underlying China’s new standing in the world, like a tectonic fault line, is an increasingly fierce competition for water that threatens to upend China’s progress. Simply put, according to Chinese authorities and government reports, China’s massive economic growth outpaces its freshwater supply.

China scholars conclude that unless there are significant improvements in pollution control, conservation, efficiency and recycling there is not enough water to 1) supply China’s massive and growing energy demand, 2) feed its rising population and 3) develop the modern cities and manufacturing centers that China plans for its dry northern and western provinces.

Change in China depends in growth, and many worry if that can be sustained, explains Kang Wu, a senior fellow and China energy scholar at East-West Center in Hawaii. “They want to double the size of the economy again in 10 years. If you look out 10, 20, 30 years, it just looks like it’s not possible.”

Chinese leaders tend not to disagree. But when asked whether water shortages could limit future growth, government authorities and business executives shrug their shoulders and say they’ll think of something. A typical response comes from Xiangkun Ren, who oversees a water-gulping program to convert coal to diesel fuel for Shenhua Group, the largest coal company in the world: “We believe that this is possible and we can do this with new technology, new ways to use water and energy.”

Indeed, China’s industrialization to date was achieved, arguably in large part, because it anticipated the contest over scarce water. The central and provincial governments enacted and enforced a range of water conservation and efficiency measures essential for China’s new prosperity. Though China’s economy has grown almost eightfold since the mid-1990s, water consumption has increased just over 15 percent, or 1 percent annually, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

The next era of industrialization and modernization confounds China’s water managers. And because of China’s commanding role in supplying, buying and pricing global markets for grain, energy and other products, the challenge should also worry consumers all over the world. Stripped to its essence, China’s globally significant water chokepoint is caused by four converging trends:

-

Over the next decade, according to government projections, China’s water consumption, driven in large part by increasing coal-fired power production, will reach 670 billion cubic meters annually – 71 billion cubic meters a year more than today.

-

China is getting steadily drier. Total water resources, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, have dropped 13 percent since the start of the century. In other words, China’s water supply is 350 billion cubic meters, or 93 trillion gallons, less than it was at the start of the century. Chinese climatologists and hydrologists attribute much of the drop to climate change, which is disrupting patterns of rain and snowfall.

-

Coal supplies 70 percent of China’s energy and sucks up a lot of water. Production and consumption of coal, two-thirds of it mined in five northern desert provinces, has tripled since 2000 to 3.15 billion metric tons in 2010. Government analysts project that China’s energy companies will need to produce an additional 1 billion metric tons of coal annually by 2020, representing a 30 percent increase. Fresh water needed for the coal sector accounts for the largest share of industrial water use in China, at 23 percent of the nation’s freshwater reserves, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. By 2020, according to government estimates, the coal sector will use 188 billion cubic meters, making up 28 percent of the nation’s total water use.

-

Production in China’s grain sector has shifted to the dry north. In 1980, almost 60 percent of China’s grain production occurred in 14 wet provinces south of the Yangtze River. Last year, over 60 percent of the 546 million metric tons of grain that China produced was grown in northern provinces, and 20 percent was produced in the bone dry Yellow River Basin, where water allotments to farmers have been cut 30 percent since 2008.

In March, China adopted its 12th Five-Year Plan, the country’s master economic development strategy, which set a new limit on energy consumption to spur efficiency and conservation measures. The new five-year plan calls for reducing water use by 30 percent for every new dollar of industrial output, the same target included in the 11th Five-Year Plan, easily met with programs to recycle water in major industries and in large cities, led by Beijing.

But a number of scholars wonder whether China is doing enough, particularly in controlling water use by the energy sector. The government considered capping coal production at 3.6 billion metric tons annually in the new five-year plan, explained David Fridley, a staff scientist in the China Energy Group at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. “It’s not at all clear from their available water supply, transportation limits, and production costs that they can sustain coal production at 4 billion metric tons per year for even a couple of years,” he noted. “Will price impacts be enough to change behavior? Or will there be absolute energy shortages?”

By insisting on developing new sources of food and carbon-based fuels drawn from the desert, China is testing the limits of its water reserves. Unless China either gets wetter or pushes harder to conserve water, the country faces a crippling energy shortage, perhaps food shortages, too, by the end of the decade.

While such outcomes challenge China’s stability, they also would tilt the economic well-being of every nation that depends on the nation’s manufacturers and competes in the energy and grain markets. After all water, food and energy are the basic fuels of China’s rapid development.

Keith Schneider, a former national correspondent and regular contributor to the New York Times, is senior editor of Circle of Blue.