What Should the White House Do About Globalization

What Should the White House Do About Globalization

Dear Mr. President,

Congratulations on your convincing win. As you settle into the Oval Office, you must address an urgent problem that went unmentioned during the campaign.

The American business community is rapidly globalizing and expanding internationally, particularly in new, emerging markets. Yet political, media and educational, let alone the broader American public, do not understand this trend and feel threatened. If nothing is done, you will face severe policy crises.

Take, for example, China. Despite the success of the Olympics, a growing number of political and media voices portray China as a new evil empire even as its importance to US business increases exponentially. The deep American recession will intensify pressures on you to retreat from international markets at the very moment the United States needs to capture the growth opportunities that those markets represent. In fact, the intellectual and political underpinning that has supported America’s economic engagement with the world could be unraveling. This would be the modern-day equivalent of the Smoot-Hawley bill of the early 1930s, widely blamed for deepening US economic isolation at precisely the wrong moment.

Here is a four-point proposal for addressing this real and pressing issue:

• Use your bully pulpit to articulate a sense of mission and explain to the American people what “globalization” means.

For nearly 30 years, ever since Ronald Reagan took office in 1980, American political leaders and economists across the political spectrum have argued that globalization is good. There was an ideological bent to it in some ways: By globalizing, Americans would export values and defeat Communism.

After that ideological battle was won, however, confusion set in. In today’s context, globalization means Americans drive to higher levels of economic sophistication, which high education levels and a robust entrepreneurial culture should enable. Other people in the world should push into new sectors that allow them to create wealth, even if it means the displacement of tens of thousands of Americans in the shoe or textile or steel industries, for example. The wealth of other nations creates new opportunities for higher value-added American goods and services. We will build their dams, highways, power systems and fiber optic networks. The net effect is that everyone can win in a globalized economic context.

One useful element of this rhetorical campaign would be improving Americans’ “economic literacy.” Increasingly obsessed with sports and entertainment, the media has retreated from this challenge.

• Create an alliance with big business by naming key chief executive officers of large multinationals to a presidential advisory council.

This council should include a range of American-born and non-American CEOs of major companies, in the manufacturing sector, in particular. Solid choices would include Rick Wagoner of General Motors and Robert Lane of Deere & Company, as well as Louis Chenevert, the new Quebec-born CEO of United Technologies Corp., and Indra Nooyi, the Indian-born CEO of PepsiCo.

These CEOs could communicate their priorities, but these relationships could also build awareness of the positive contributions such companies make to the US economy even while you hold their feet to the fire, in the most diplomatic way, to remain true to the vision of globalization as a win for America.

In developing these relationships, you could visit UTC’s Pratt & Whitney facilities in Hartford, Connecticut, where 26,000 Americans build aircraft engines for the world or Waterloo, Iowa, where Deere builds diesel engines for export to the world. In each case, you could draw a direct connection between high-qualiy jobs in the US and globalization.

And in your international travels, you could visit GM’s factory in Shanghai to illustate that the company now sells 1 million vehicles a year in China, making it the No. 1 auto manufacturer there. The Chinese, it turns out, love Buicks. And in India, Ms. Nooyi would spotlight how her company strives to satisfy the thirst and hunger of a nation whose population now stands at 1.1 billion.

In each of your foreign trips, you could visit McDonalds, Citibank and other iconic American brand-name businesses, spotlighting how US engagement with the world creates shareholder value and wealth in general.

• Open up the export floodgates for smaller and medium-sized companies.

Although some smaller American companies excel in international markets, the vast majority lag behind. The governmental apparatus for assisting these companies is hopelessly fragmented and out of date. You should create an agency that encompasses the Department of Commerce – itself a dumping ground for political appointees, a practice that you should avoid – the Small Business Administration, Overseas Private Investment Corp., the Export-Import Bank and dozens of other agencies that monitor or regulate exports. This effort should be coordinated with states that boast export-development offices. The goal should be a system of offices throughout the country that provide real information about export opportunities and practical advice on how to grasp those opportunities.

Two other key elements of this export initiative would be improving the access of new-to-export companies to export financing, a sector that crisis-ridden American banks ignore, and easing the export-control bureaucracy in Washington that stifles many would-be exporters of technologically advanced products.

In your domestic travels, you could meet with exporters and organize town-hall discussions, convincing millions of Americans that jobs and quality of life are directly tied to international markets.

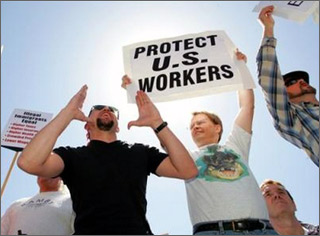

• Make convincing progress on redressing labor and environmental issues, both at home and abroad.

One of the strongest intellectual arguments against globalization has been that business leaders invoke it merely as a means to sidestep their responsibilities to maintain environmental and labor standards. Clearly, some have done this. For years, Nike paid workers in China or Vietnam $1 or so a day, while polluting nearby rivers and air. Other companies closed factories in the US, leaving environmental hazards behind as well as workforces unable to redeploy themselves. These abuses buttressed the unfortunate argument that globalization was just a slogan to help the rich get richer.

You could spur progress on these issues by visiting factories in China, Vietnam or Bangladesh. Obviously, you have limited power outside the US, but your attention to the issues would carry symbolic power. At home, the most pressing issue is to jumpstart the essentially failed effort to redeploy displaced workers. Various programs are in place, but they are underfunded, fragmented and ineffective.

If the American people could see workers who have been fired from an electronics factory in North Carolina receiving a year of training, then winning key jobs in Research Triangle, it would demonstrate that an American commitment to globalization is a win-win. That same principle should be applied to the educational system as a whole – you can visit Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh or Purdue in West Lafayette, Indiana, and show people that strong educations provide skills that allow individuals and communities to survive and indeed thrive in a globalized economy. In the final analysis, skills are the bedrock of international success. But that message has been obscured because most educators themselves have been trained in a purely domestic context.

In conclusion, Mr. President, you could change the tone of the highly polarized debate about globalization by demonstrating that it isn’t an ideological absolute. Globalization has advantages and disadvantages that must be actively managed. As a matter of national economic policy, your goal as president should be to maximize the benefits to the American people while mitigating the costs. By doing that, you could renew the intellectual and political legitimacy that globalization once had, but which, unfortunately, is in danger of being lost. If the consensus supporting globalization unravels, your ability to guide the American economy through a difficult period will be severely constrained.

William J. Holstein is a New York-based business journalist and author who writes for The New York Times weekend business sections and Strategy + Business, among other publications. He specialized in international business issues while on staff at Business Week, U.S. News & World Report and Chief Executive magazines. His website is www.williamholstein.com