When Chinese Martial Arts Flies Through the Global Box Office

When Chinese Martial Arts Flies Through the Global Box Office

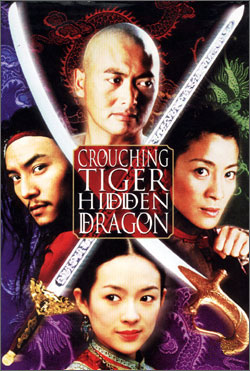

Was Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon a slickly made Chinese epic or a Hollywood blockbuster painted with a Chinese brush? Whichever way one characterizes Taiwan-born director Ang Lee's film, this global box office hit does suggest the need for a new way of looking at contemporary cinema.

Lee's martial arts melodrama Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon was a worldwide cinematic phenomenon in 2000-2001. Made with a relatively modest budget of $15 million, the film not only won critical acclaim at the Cannes Film Festival but grossed over $200 million worldwide and thrilled audiences from Singapore to San Francisco. Surprisingly, it earned over half its box office receipts in the United States: in a market notoriously hostile to foreign films, Crouching Tiger made the rare transition out of the art-houses and into the multiplexes where the big money is made. In doing so it became the most successful foreign-language film in US history and the first Chinese-language film to find a mass American audience.

Part of the film's significance derives from the way it displays the simultaneously localizing and globalizing tendencies of our current moment. In its visual and narrative content, the film comes across as resolutely Chinese local. Based on a Chinese novel and featuring ethnic Chinese actors, it offers sweeping vistas of mainland China and brings the Qing dynasty era to life through sumptuously detailed settings, costumes, and decor. The film's production, in contrast, was astoundingly global. Executive producer James Schamus, an American, put together a complex financing scheme based on advance selling the international distribution rights to a bevy of American, Japanese, and European companies. Much of the money came from various divisions of Tokyo-based Sony: Sony Pictures Classics in New York bought the US distribution rights; Columbia Pictures in Hollywood picked up rights for Latin America and several Asian territories; Columbia Pictures Asia, a Hong Kong-based production entity, contributed funds; and Sony Classical music financed the soundtrack. The actual cash for the film came from a bank in Paris, while a completion bond company in Los Angeles insured the production. The New York-based Schamus also co-wrote the screenplay, working with Taiwan-based writer Wang Hui Ling in a process that entailed translating drafts back and forth between English and Chinese. The actual production of the film involved four different companies in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China, along with a subsidiary in the British Virgin Islands. Post-production work was similarly dispersed: the soundtrack was recorded in Shanghai, sound looping took place in Hong Kong, and the film was edited in New York.

The simultaneously local and global nature of Crouching Tiger has led many viewers to grapple with the film's national-cultural identity. Some have tried to wish this complexity away by identifying the film in singular terms as a Chinese, Hong Kong, Taiwanese, or even Hollywood film. The more analytical responses have unfolded along a continuum whose poles are marked by two popular models for thinking about cultural globalization. Some critics have seen the film as an act of local Asian resistance to global Hollywood, while others have read it as a culturally inauthentic Asian film that has been corrupted by global Hollywood's cultural imperialism.

The desire to read Crouching Tiger as a work of local culture is not entirely misplaced. In interviews Lee has described it as a "Chinese film" and cast it in cultural-nationalist terms as an expression of themes that are in the Chinese "blood".

Anthropologist James Clifford describes diasporas as being oriented along "an axis of origin and return," by which he means that the departure from home is usually followed by an intense desire to return.

Rather than classifying Crouching Tiger as a "Chinese" film, I want to suggest that we read it as a symbolic act of return by a diasporic Chinese to his homeland. Lee has never lived in China, and before he spent five months filming there he had made only one brief visit, making his return also a first encounter. Like the rest of his Taiwanese generation, he did not really know China. He grew up with a sense of connection to the mainland, but that connection was always filtered through other people, institutions, and mass media. "I ... found out about the old China," Lee explains, "from my parents, my education and those kung fu movies."

This bond with the homeland is offset in diasporic culture by what Clifford calls "selective accommodation," that process through which a member of a diaspora engages with and partially integrates into the economic, political, social, and cultural life of the host country that he or she actually inhabits.

Lee points to this process of selective accommodation when he describes Crouching Tiger as an attempt to merge Chinese and Western styles of filmmaking. The Chinese martial arts film, in the eyes of Lee and many others, has traditionally been hobbled by a lack of integration between narrative and spectacle; this means that the fight scenes, while highly sophisticated in terms of physical skill and cinematic presentation, tend to exist largely apart from the story. Lee wanted to retain the satisfying visual spectacle of the martial arts scenes, while at the same time using them to move the narrative forward, develop the characters, and illustrate the themes. Lee saw this subordination of martial arts spectacle to the demands of the narrative as the Western aspect of the film.

Lee achieves this subordination by borrowing some of the conventions of the Hollywood musical, a genre which had long ago solved the problem of integration. Lee begins by slowing down the frenetic pace of the typical martial arts film, spacing the fight scenes widely apart and giving the story and characters a chance to develop. The first fight doesn't take place until fifteen minutes into the film, and when it does appear, it marks a break from the world of the narrative. In the world of a Hollywood musical number, people spontaneously break out into song and dance; in the world of Crouching Tiger's martial arts fights, physical laws and social rules are violated with impunity. These fight scenes, like Hollywood musical numbers, represent a kind of utopian space in which people can fly through the air and sometimes break free of their class, family, and gender constraints.

As much as the film distinguishes the narrative and the fight scenes from each other, however, it also integrates them tightly with each other. Like a romantic waltz in a musical, the fights communicate visually what is difficult for characters to express verbally. When the older, dutiful Shu Lien and the younger, rebellious Jen confront each other on the rooftops, they perform the film's central theme: the tension between the sense of obligation to others and the desire to pursue one's self-interest. Jen's vigorous fight in the desert with her lover Lo communicates their mutual sexual attraction as well as their shared social defiance; Li Mu Bai's dreamy encounter with Jen atop the bamboo trees, in which he seems to gaze down upon her as she passively reclines with prettily disheveled hair, suggests a troubling erotic dimension that extends beyond what a master should feel for a disciple; and Jen's besting of a score of male combatants in the teahouse scene enacts her self-liberation from her class and gender roles. In these scenes Lee harnesses Yuen Wo-ping's vertiginous martial arts choreography and subsumes it to the demands of Hollywood-style narrative. "In other movies," Lee says, "flying is an effect. But here it is part of the storytelling."

Crouching Tiger is representative of an emerging "global cinema", which is characterized by movies that cannot be identified in singular national-cultural terms and that muddy the distinction between Hollywood and "foreign" film. The production and consumption of these films takes place on a global, rather than a national scale, and the aesthetic affiliations they make similarly cross multiple cultural boundaries. The emergence of such a global cinema makes it vitally important to develop critical tools that can read films from a transnational perspective.

1 Variety.com, Weekly Box Office, July 27 - August 2, 2001.

2 James Schamus, "The Polyglot Task of Writing the Global Film," New York Times, November 5, 2000, Section 2A, p. 25, 32. Claudia Eller, "Company Town; The Biz; Funding for 'Crouching Tiger' a Work of Art," Los Angeles Times, December 12, 2000, from Lexis-Nexis, page C9.

3 Salman Rushdie, "Can [INSERTED SPACE] Hollywood See the Tiger?", New York Times, March 9, 2001, page A19. Derek Elley, "Asia to 'Tiger': Kung-Fooey," Variety.com, posted February 7, 2001.

4 "A Director's China Dream," Newsweek Pacific Edition, July 17, 2000, from Lexis-Nexus, p. 60. Rick Lyman, "Crouching Memory, Hidden Heart," New York Times, March 9, 2001, page B27.

5 James Clifford, Routes: Travel and Transculturation in the Late Twentieth Century (Cambridge: Harvard, 1997) p. 269.

6 "A Director's China Dream," Newsweek Pacific Edition, July 17, 2000, page 60, from Lexis-Nexis..

7 "A Director's China Dream," Newsweek Pacific Edition, July 17, 2000, page 60, from Lexis-Nexis.

8 Clifford, Routes, 251.

9 Devin Gordon, "It's the Year of the Dragon," Newsweek, December 4, 2000, page 60, from Lexis-Nexis.

Christina Klein is Associate Professor of Literature at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.