When Christian Power Was Arrayed Against a Judeo-Muslim Ideology

When Christian Power Was Arrayed Against a Judeo-Muslim Ideology

NEW DELHI: In recent years, especially in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, Islam has been increasingly presented as an “implacable” enemy of the other two monotheist religions – Judaism and Christianity. Yet history tells another story. For a long period militant Christianity was arrayed against what can be called a Judeo-Muslim world – especially in India, which during the 16th and 17th centuries witnessed a protracted struggle between the rising Portuguese-Christian colonial power and the subcontinent’s established Islamic dynasties.

In the 50 years following Vasco da Gama’s violent landfall on the Malabar Coast in 1498, the Portuguese Estado da India became a formidable force throughout the subcontinent. By 1550, the Portuguese directly ruled many of India’s best western ports – from Diu in Gujarat and Bombay in Maharashtra to Cochin in Kerala – as well as the jewel in its crown, Goa on the Konkan coast. They also possessed the Coromandel Coast colony of São Tomé de Meliapor in what is now Chennai. These settlements allow the Portuguese to gain a stranglehold over the lucrative spice trade. Informally, the Portuguese also controlled much of the salt trade in the northern Bay of Bengal: The state had imposed a cartaza system that demanded merchant vessels in the area to pay taxes to the Portuguese.

All this would suggest that the Portuguese presence in 16th-century India was one of imperious domination. Yet the records of the Bahamani sultanates – the collection of independent Muslim states stretching across the middle band of the subcontinent – include the names of several Portuguese citizens who came not to conquer but rather to serve Muslim masters.

To give just two examples: Sancho Pires, who came to Goa in the 1530s, relocated to the sultanate of Ahmadnagar. Pires proceeded to find service in the Ahmadnagar army, first as a bombardier and later as captain of the cavalry; he became a favorite of Burhan Nizam Shah, the sultan, and eventually took the name of Firangi Khan. In the 1590s, Fernão Rodrigues Caldeira also quit Goa to serve as an advisor to Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, the sultan of Golconda. Pires and Caldeira, separated by several decades, had something in common beyond Portuguese names: Both were from New Christian families – that is, Iberian Jewish families forced to convert to Christianity after the reconquista of 1492, when Jews and Muslims were expelled from the peninsula. In Spain, the Inquisition hunted down any suspected of practicing non-Christian faiths. Portugal initially held off on instituting the Inquisition. In 1496, King Manuel promised not to inquire into New Christians’ faith for a grace period of 30 years; he renewed his pledge in 1504, and it remained in force until 1534. After all, Portugal’s growing maritime power was dependent not just on skilled Jewish labor – Vasco da Gama’s navigator-astronomer Abraão Zarcuto, for example, was a Jew – but also on wealthy New Christian merchant families with international, or “Judeo-Muslim,” connections extending through North Africa and the Ottoman Empire to the Arabian Peninsula and the Indian Ocean.

I use the term “Judeo-Muslim” deliberately and perhaps a little provocatively. The term “Judeo-Christian” has been bandied around for some time to suggest a longstanding natural bond between the two religious traditions connected by that hyphen. In the United States in particular, some have used the term more recently to imply that Muslims are natural adversaries of both Jews and Christians. Yet for the better part of two millennia, Jews were bonded to Christians primarily as the latter’s enemies.

As the history of Jews in Spain and Portugal suggests, the multicultural bond with the greater historical resonance was Judeo-Muslim. Iberian Jews such as the famous Andalusian philosopher Maimonides, spoke, wrote and dreamed in Arabic; their cultural reference points were Arabic; and their gastronomic preferences were also influenced by their Moorish neighbors. As late as 1490, the Jewish population of the now substantially shrunken Al-Andalus, diminished to the Emirate of Granada by two centuries of Christian reconquest, was still deeply versed in Arabic language and culture. Even in Christian-ruled areas such as Castile and Portugal, Sephardic Jews were speakers of Ladino – a vernacular mixture of Spanish, Hebrew, Aramaic and Arabic. In Ladino, for instance, Sunday is not “domingo” as in both Spanish and Portuguese, but “alhad,” derived from the Arabic “alhat.” The Ladino word for freedom is not the Spanish “liberdad,” but “alforria,” derived from the Arabic “al hurriya.” Clearly Sephardic Jews did not associate the idea of liberty with Spanish Christian rule.

The mass expulsions of 1492 violently disrupted this Judeo-Muslim nexus, but did not end it. By and large, the nexus was simply dispersed to other parts of the world: Many expelled families migrated to Morocco and cities of the Ottoman Empire such as Algiers, Cairo and Istanbul, where communities of Jews and Muslims lived in close proximity. And after 1534, when the Inquisition was finally introduced in Portugal, a number of New Christians – including Pires and Caldeira – migrated to India. It’s perhaps no accident that they often enjoyed more kinship there with local Muslim communities than with Portuguese Christian colonists.

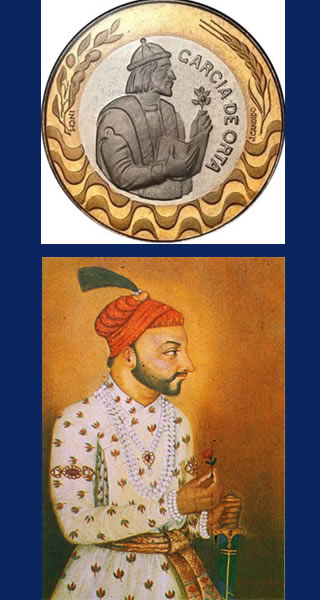

The year 1534 was also the year when – now celebrated as a Portuguese hero and patriot, largely for writing what’s commonly regarded as the first treatise on tropical medicine – migrated to Goa.

In 1534, Orta relinquished a prestigious chair of medicine at the University of Lisbon to accompany the newly appointed viceroy, Martim Afonso da Sousa, to Goa as his personal physician. When da Sousa’s term expired in 1538, Orta did not return. And that was because he had a secret: He was an undercover Jew and had almost certainly come to Goa to flee the specter of the Inquisition. He was joined there by his mother, Lenore, and sister Catarina, and he married a New Christian cousin of his, Briana de Solis, whose family had also migrated to Goa.

The Inquisition eventually arrived in Goa in the 1550s, partly at the urging of the future St. Francis Xavier. Around this time, Orta mysteriously relocated to the Ahmadnagar sultanate, where Sancho Pires was also serving the ruling Nizam. Orta had an advantage in Ahmadnagar inasmuch as he was conversant in Arabic, the lingua franca of the Nizam’s court. Orta met many Arabic-speaking hakims, or doctors, from whom he learned about the tropical medicine he would later write about. During his period of service in Ahmadnagar, Orta dispensed a prescription in Arabic for the Turkish Mamluk Sultan of Bidar’s brother, Hamjam – an extraordinary display of multiculturalism of the Arabic-speaking Indian world. In Muslim Bidar, a former Turkish slave from Christian Georgia, could converse in Arabic with a Sephardic Jew from Portugal.

Orta returned to Goa and published his treatise in 1561, which won him fame and perhaps some respite from the Inquisition. He died a celebrity of sorts and was buried in the principal Goan cathedral. But the Inquisition finally caught up with him. A year after Orta’s death in 1568, his sister was burned at the stake in Goa as “an impenitent Jewess.” And Orta’s remains were dug up, incinerated, and flung into the Mandovi River.

Garcia da Orta, like Sancho Pires and Fernão Rodrigues Caldeira, should be thought of not as Portuguese but Un-Portuguese. Hounded and dispossessed by the Portuguese state, these men like their ancestors were more at home in a Judeo-Muslim world.

Jonathan Gil Harris is dean of academic affairs and professor of English at Ashoka University in Delhi, India. The author of five books on the drama and culture of Shakespeare and his contemporaries, he has just published a new book, The First Firangis: Remarkable Tales of Heroes, Healers, Courtesans, Charlatans and Other Foreigners Who Became Indian (Aleph Books, 2015). Read an excerpt.