When Millennia-Old Mummies Threaten National Identity

When Millennia-Old Mummies Threaten National Identity

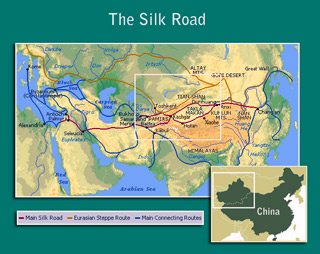

CHICAGO: A series of Tweets broke the good news the morning of February 11th: “The MUMMIES are back for our ‘Secrets of the Silk Road’ exhibition!” announced the University of Pennsylvania Museum and Archaeology and Anthropology at 9:03 am. Then again at 10:02, “’Secrets of the Silk Road to open with Mummies, artifacts from China,” and again at 11:15 and 11:36. Why such breathless notice about mummies three millennia old? Because the exhibition marks a minor victory of scholarship against the state bureaucracy’s management of the past.

The announcement gladdened all who value museums. Ten days earlier, the exhibition had seemed doomed. The New York Times had reported that the exhibition, organized by the Bowers Museum in Santa Ana, California, and shown there and at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, had been “modified” – the Penn Museum’s word – and would consist only of photographs, multimedia presentations and re-creation of an excavation site. The Chinese government had requested that none of the artifacts approved for loan in June 2010 could be exhibited, curators explained. This included two mummies from the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region Museum, 3,500 years old, with what are described as Caucasoid features with long noses and light hair – features raising questions about whom first settled that part of what’s today western China.

Rumors flew and facts were few about the change of mind. On February 7, National Public Radio reported that Tidin Xhang, first secretary of the Chinese Embassy’s cultural office in Washington, had explained: “According to the law for protection of archaeological exhibits, the maximum amount of time to have a tour overseas is eight months. The law is the law, and we cannot go contrary to the law.” The release contradicted a March 2010 article in China Daily Online reporting that the exhibition would travel to three US venues, including Philadelphia, and the exhibition’s publicity describing a tour lasting more than a year.

Then, on February 9, the Philadelphia Inquirer cited Chinese Embassy spokesman Wang Baodong as saying that the “Secrets of the Silk Road” exhibition had never been approved for display in Philadelphia, blaming the confusion on poor planning by the museum: “For such a big exhibition, you’ve got to have good planning in the first place. So, again, Philadelphia was not a planned stop.”

During the nine days between the Chinese government’s refusal to allow the museum to display the mummies and accompanying artifacts and Penn Museum’s announcement that the mummies and artifacts would indeed be included in the exhibition beginning February 18, high-level discussions took place between US and Chinese officials. In an official statement, the museum’s director gratefully acknowledged contributions of US and Chinese ambassadors, and other senior Chinese officials “who have so generously assisted us in making all these artifacts available.”

Clearly the decision to prohibit the exhibition of materials was taken at a high governmental level because apparently much more hangs on the mummies than regulations about exhibition abroad. The New York Times speculated: “Chinese authorities have faced an intermittent separatist movement of nationalist Uighurs, a Turkic-speaking Muslim people who number nine million in the region, and Uighur nationalists have used evidence from the mummies – whose corpses span thousands of years – to support historical claims to the region.” Chinese rule over the area is contested by Uighurs, a Turkic people who sporadically engage in demonstrations against Beijing.

Three years ago, The New York Times reported on the mummies and their host museum in Urumqi, the capital city of the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region, and noted that “At the heart of the matter lies these questions: Who first settled this inhospitable part of western China? And for how long has the oil-rich region been part of the Chinese empire?”

Politically, the region came under Chinese control only under the Qing Emperor Qianlong in the 18th century. Uighur separatists resist the term Xinjiang – which means “New Frontier,” given to the region by the Chinese in 1884 – and prefer East Turkestan.

In the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, violence broke out in Xinjiang amidst increasing Beijing-directed cultural change in the region: standardizing the local education system on the Beijing model; changing the language of instruction from Uighur to Mandarin; replacing Uighur teachers with Han Chinese ones; organizing public burnings of Uighur books; and prohibiting traditional Uighur customs such as religious weddings, burials and pilgrimages to tombs of local saints.

Most visibly, the Chinese government accelerated the razing of old Kashgar for what Beijing claims are safety reasons: The buildings were said to be too dangerous in the region’s earthquake zone. The plan is to demolish 85 percent of old Kashgar and build in its place a mix of mid-rise apartments, plazas, avenues and reproductions of ancient Islamic architecture “to preserve the Uighur culture.” A recent article in China Daily Online reported that more than 1,600 “officials and experts from 19 provinces and municipalities have arrived to work in Northwest China’s Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region in a partnership program to assist local development.”

Xinjiang, rich with oil and natural gas, is a Chinese bulwark against Islamic Central Asia. As with Tibet, the central government in Beijing answers separatist threats with a combination of police action and economic development. It also would like to reshape history to reinforce its claim over the region. Hence, the mummies in the Urumqi museum and their historical record carry political significance.

Uighur separatists interpret the mummies as evidence that the first peoples to settle the area came from west and not the east, supporting their historical and political claims to the region. Some scholars have called for genetic testing as a means of providing a richer understanding of the regions’ early inhabitants.

Victor Mair, a professor of Chinese Language and Literature, was cited in the 2008 New York Times article as expressing frustration that scientific testing wasn’t taking place on what he called the Tarim Mummies, a more politically neutral term referring to the region’s Tarim Basin where they were found. “In terms of advanced scientific research on the mummies,” he said, “it’s just not happening.” Elsewhere in an article published by Agence France Presse, the scholar was quoted as saying, “It is unfortunate that the issue [of genetic testing of the mummies] has been so politicized because it has created a lot of difficulties.”

Mair, based at the University of Pennsylvania, is a reputable scholar of international standing. Over the course of the 1990s, Mair led an interdisciplinary research project on the mummies of Eastern Central Asia, resulting in three television documentaries, a major international conference, numerous articles and a book: “The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples of the West.” He’s also a consultant on the Penn Museum exhibition and was quoted as explaining the absence of the mummies in the Penn exhibition as a “horrible bureaucratic snafu.”

More than bureaucratic bungling may be involved. Presumably to avoid yet another issue roiling US-China relations, Beijing relented on displaying the mummies in Philadelphia, but would like this exposure to be as short as possible. Less international attention to the Caucasian-looking mummies is better for Chinese control over Xinjiang. The mummies are silent, but what they say about the past disturbs the present-day rulers of the land where they breathed their last.

Comments

Dr. Victor Mair, a sinologist turned self-proclaimed "archaeologist", has tendency to promote use of modern Uyghur terms, in place of ancient Han Chinese, Tocharian and Khotanese Saka usage, for historical sites in Xinjiang.

This Penn Museum exhibition was staged, in conjunction with 'Silk Road Symposium' (a pure scholarly discussion). Regretfully, in his presentation, Mair attempted to inject, modern politics into the mix. Hence, not surprisingly, he incurred wrath of Chinese officials.