Why Does Hollywood Dominate US Cinemas?

Why Does Hollywood Dominate US Cinemas?

CAMBRIDGE, MASS.: Taking a glance at the marquee of a typical American multiplex, one might think that only Hollywood can make movies. While obviously not the case, it is true that few foreign films make it onto American screens. In 2001, imports represented less than 1 percent of all films shown in the USA. Free traders would argue that Americans simply prefer Hollywood movies, but the real reasons for this imbalance are more structural than cultural. The market for foreign films has contracted in the US over the past thirty years, due to the rise of American independent film, the decline in independent theaters, and the restored vertical integration of the US film industry. In such an environment, the gate-keeping role played by American distributors of foreign films becomes ever more crucial.

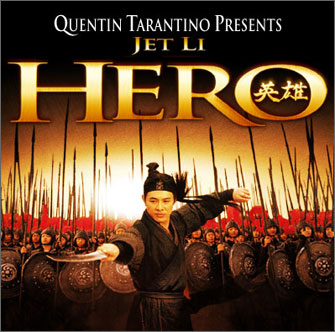

Advocates of world cinema have long complained about the threat posed by Hollywood's global dominance to fragile national film cultures, but now fans of American film are starting to protest as well. David Kipen, writing in the June issue of The Atlantic, argues that Hollywood is turning its back on American viewers and producing films primarily for its lucrative overseas audience instead. The result is a stream of formulaic studio blockbusters that feature beefed-up spectacle, dumbed-down dialogue, actors chosen for their international appeal, and little genuinely American cultural specificity – movies like "Troy", which has earned a respectable $133 million at home and a whopping $356 million abroad. If Hollywood is making movies for the world, asks Kipen, who is making movies for America? One counterintuitive answer may be foreign film makers such as Zhang Yimou, whose martial arts film "Hero" is scheduled to open in the US on August 27. Whether "Hero" will make it into your local multiplex remains to be seen.

Zhang Yimou is best known to Americans as the director of the Chinese art-house classic "Raise the Red Lantern" (1991). But like other foreign directors concerned about Hollywood's growing presence in their countries, Zhang is turning his efforts to more commercial fare that will attract larger audiences. And like Hollywood producers, he has one eye on the export market. The first result of his efforts is "Hero", one of a new breed of foreign films that emulates global Hollywood's style while also expressing a distinct national culture.

Like Hollywood's blockbusters, "Hero" boasts spectacular action scenes, CGI special effects, and a roster of internationally known stars, including Jet Li ("Cradle 2 the Grave"), Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung ("In the Mood for Love"), and Zhang Ziyi ("Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon"). At the same time, however, it adheres to the genre conventions of the Chinese martial arts film and retells a well-known story drawn from Chinese history about attempts to assassinate the country's first emperor. The result of this global/local balancing act is a visually slick film with a distinctly Chinese feel that has broken box office records at home and performed well in Asia and Europe. With $100 million in box office receipts to date, it is the most financially successful mainland Chinese movie ever made.

Other national film industries are pursuing a similar global-local strategy. This summer Hollywood-influenced local films are besting American imports in South Korea ("Taegukgi"), Russia ("Night Watch"), and Germany ("(T)Raumschiff Surprise – Periode 1"), prompting giddy speculation about the vitality of these industries. While not all of these films have cross-cultural appeal, the rights of some have already been sold to foreign distributors. Even as one applauds these films' domestic and export success, however, it raises difficult questions. Considered in aesthetic terms, are these movies on a par with the art films that many of these industries used to make? Are they genuine expressions of a distinct national culture, or just thinly localized knockoffs of the dominant Hollywood product?

No one knows whether any of these crowd-pleasing films will make it into the US, which is the world's largest film market. Even with demonstrated global appeal, "Hero" has had a difficult time and its fate remains uncertain. Released in China in 2002, it has been withheld from American viewers for nearly two years, despite garnering an Academy Award nomination for best foreign language film and rave reviews by American critics who have seen it at film festivals. And it isn't clear whether "Hero" will open wide in multiplexes across the country like a mainstream commercial film or only in a few cities like an art film.

That decision, and indeed the movie's entire American fate, rests largely in the hands of Harvey Weinstein, co-chairman of Miramax Films, which owns the North American rights to "Hero". Miramax is one of the largest distributors of foreign films in the US, and it deserves credit for helping to introduce Americans to East Asian art cinema and for popularizing Hong Kong action film in the 1990s. In recent years, however, Miramax has come to be seen as an obstacle rather than a conduit to the circulation of Asian films in the US.

The company's aggressive leadership and deep pockets have allowed it to pay top dollar for desirable foreign films, thereby keeping them out of the hands of competitors. Instead of releasing all the films it buys, however, Miramax has inexplicably shelved quite a few of them, keeping them off the market for years or giving them such a limited release that few Americans have a chance to see them. Although it paid $20 million for the rights to "Hero", Miramax sat on the film for almost two years. According to The New York Times, it only agreed to release it after being pressured by the Chinese government and receiving extra marketing funds from Disney, its parent company, which has close business ties to China and is building a theme park in Hong Kong.

When Miramax does release Asian films, it often "sanitizes" them first – by re-editing them, dubbing them into English, or adding new subtitles and soundtracks – so that their cultural difference will be within the bounds of what it thinks American viewers will accept. Harvey Weinstein reportedly demanded that Zhang trim the running time of "Hero" by about eighteen minutes, in anticipation of its US release.

When observers try to explain the lack of foreign films in US theaters, they often trot out the hoary claim that Americans don't like to read subtitles. But the runaway success of "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" (2000) and "The Passion of the Christ" (2004) should put that maxim to rest. Rather than explain the dearth of foreign films in terms of cultural preference, critics should focus on the structure of the US film industry, including the gatekeeper function played by distributors. To date, Miramax seems to have been stymied by the newest generation of commercial Asian films whose hybrid global/local identity challenges older notions of foreign films as either highbrow "art" or lowbrow "action." If Miramax gives "Hero" a wide release, the company might appease American film lovers angered by its treatment of Asian movies. It could also send a signal to foreign film industries that their new style films have a chance at the American market. For the sake of cinematic diversity, let's hope Miramax casts a wide net.

Christina Klein teaches literature and comparative media studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She is the author of “Cold War Orientalism: Asia in the Middlebrow Imagination, 1945-1961” (University of California Press, 2003).