Why Does One Country Draw More Investment Than Another?

Why Does One Country Draw More Investment Than Another?

WASHINGTON: Developing countries overall have grown faster than rich countries over the past 15 years. However, this generalization masks very divergent growth rates; while some poor countries grow at the fastest rates in the world, others languish or even decline.

A recent study conducted by the World Bank in four countries - Bangladesh, China, India, and Pakistan - demonstrates this variance. The four had similar per capita GDP in 1990, but within a decade China's growth has rocketed; Bangladesh and India have grown moderately; and Pakistan not at all.

Some believe that these differences reflect the extent to which the countries are taking advantage of opportunities afforded by globalization. The recent global attitudes survey by the Pew Research Center for The People and The Press (2003) (See "Globalization with Few Discontents?") found robust popular support for economic integration. The study showed that 90 percent of households in China saw expanded international trade and business as beneficial, as compared to 84 percent in Bangladesh, 69 percent in India, and 78 percent in Pakistan. The growth performance of these four countries (and of developing countries in general) is highly correlated with the increase in their openness over the 1990s.

This correlation between integration and growth begs the question: Why have some countries integrated while others have not? The answer may lie partly in trade policies. Of the four countries discussed, China has been the most aggressive in terms of liberalizing trade. By the end of the 1990s, its average import tariff rate had declined to 16.8 percent - a rate lower than in South Asia.

However, the whole story is more complicated. Pakistan had a fairly significant decline in average tariff rates as well, but no growth. Bangladesh's average tariff rate at the end of the 1990s (22.2 percent) was comparable to China's, and the country saw a significant increase in trade integration. Still, Bangladesh's performance lags well behind China's.

The World Bank's study suggests that trade liberalization must be complemented by a sound investment climate if developing countries are to achieve high growth rates. A country's institutions, policies, and regulations play integral roles in encouraging foreign investment. And, if the local government is highly bureaucratic and corrupt, or if the government's infrastructure and financial services are inefficient, firms will not receive reliable services. Such conditions will make it difficult to persuade entrepreneurs to invest in potential export opportunities, since their returns will be low and uncertain.

In an effort to study the effects of investment climate on growth, the World Bank has collected data from firms on how institutional and policy weaknesses affect them. The World Bank has collaborated with in-country partners on large, random surveys of enterprises in Bangladesh, China, India, and Pakistan. These surveys gathered data on ownership (foreign or domestic), sales (export or domestic), inputs, and outputs, as well as on objective aspects of the investment climate, such as customs regulations, telecommunications, and the reliability of power.

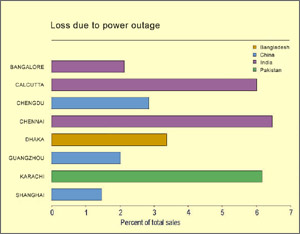

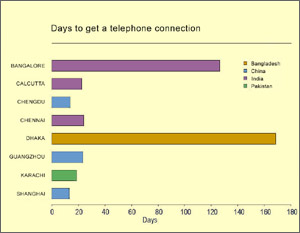

Based on the surveys, it seems that customs clearance is faster in China than in Bangladesh, and faster in Bangladesh than in Pakistan. Since time delays and service breakdowns are inconvenient and costly to firms, China clearly provides the best investment environment. China is equally efficient on all counts investigated, including customs clearance, telecommunications, and the reliability of power.

However, each location has its relative strengths and weaknesses. In China, for example, the state-owned banking system provides poor services to the firms (largely privately owned) in the sample. Moreover, there are significant differences in different cities within a country.

The World Bank also made models to estimate the probability that a firm will export and the probability that the firm is foreign to see how much investment climate influenced the number of foreign firms in a country. Based on these models, there is a clear relationship between investment climate indicators and international integration: exporting and foreign investment are much more common in locations where hassles and delays are low. The study controls for a number of geographic factors such as distance from major markets, distance from ports, and population of the city. Moreover, the study takes into account country dummies. That is, it accounts for the fact that there may be other conditions in China (political stability, culture, size) that make it particularly attractive to foreign investors and traders.

Beyond these country-level factors, the survey finds that investment climate is important for international integration. Thus, according to World Bank estimates, if Calcutta could foster Shanghai's investment climate - in terms of customs reliability, infrastructure, and financial services - the number of firms exporting from the city would nearly double from the current 24 percent to 47 percent - an amount comparable to what is found in coastal Chinese cities. Similarly, the share of foreign-invested firms would increase by more than half, from the current 2.5 percent of firms, to 3.9 percent.

Clearly, natural geography and agglomeration economies are also fundamental factors in growth; manufacturing plants are not randomly distributed around rural locations. Most of the locations covered by the World Bank study are large cities, however, and many are ports, making them far from completely isolated. Rather, such port cities are perfectly located to access the international market. Yet even this big port city advantage can be easily undone by poor local governance. The relatively poor performance of cities like Calcutta (India), Karachi (Pakistan), Chittagong (Bangladesh), and Tianjin (China) as compared to Guangzhou and Shanghai in China makes this reality abundantly clear.

Thus, the reason China's cities - and thus China itself - have grown so much in the past decade, where other developing countries have floundered, is because it has fostered a uniquely attractive investment climate. This investment climate has allowed companies to not simply sow investments, but also reap profits. Such success stories have lured other firms to China, increasing the amount of foreign investment as well as the number of firms selling Chinese manufactures on the international market.

In a companion study, The World Bank found that investment climate is related to high productivity, wages, and profitability at the plant level. The results of the study suggest that high productivity results, at least in part, from the international integration that thrives in countries with sound investment climates. Foreign firms tend to have higher productivity (owing to superior technology or management), as do firms that produce exports. It remains unclear whether exporting directly increases productivity; but exporting may well provide already highly-productive firms with the opportunity to expand to a scale that would otherwise be unattainable.

Given the large differences in investment climate found in the World Bank surveys, it is ultimately un-surprising that the level of international integration varies so greatly from location to location. The evidence shows that the interaction of open trade and investment policies with a sound investment climate has created especially dynamic growth in a number of Chinese cities. The uniquely attractive conditions in these cities - their infrastructure, governance, and reliable services - explain why China has flourished, while other developing countries continue to lag. China's good investment environment brought firms into the country, and these firms have integrated China with the world.

David Dollar is Director of Development Policy at the World Bank and co-author, with Mary Hallward-Driemeier and Taye Mengistae, of the report “Investment Climate and International Integration,” presented at the conference “The Future of Globalization: Explorations in Light of Recent Turbulence” at Yale University, October 10, 2003. Conference Schedule.