The WikiLeaks Ravage – Part I

The WikiLeaks Ravage – Part I

NEW DELHI: The release of diplomatic cables from US embassies across the world, courtesy of WikiLeaks, is unprecedented only in the sheer volume of material and the extraordinary range of subjects they cover. In 1979, the world was treated to a smaller but nevertheless revealing set of cables from the US Embassy in Teheran taken over by Iranian revolutionary guards. Then, too, there was embarrassment, but the impact was limited in scope. Diplomatic behavior did not change. The willingness to exchange information and assessments on a confidential basis, the essence of diplomacy, was hardly affected. After WikiLeaks, diplomats and leaders will be mindful of what they say to foreign interlocutors, out of fear of reading their comments in the newspapers the next day, but how long this lasts remains to be seen.

If this release is a one-time event, the impact may recede over time. After the dust settles, it will be business as usual. If there are serial leaks, the fallout will be more enduring.

The material itself is not as damaging as the fact that it involves ongoing events and dramatis personae in key leadership positions. No doubt, for some time to come, political leaders, senior officials and diplomats will be wary about trading confidential information and candid assessments with one another.

This can only be a loss to the craft of diplomacy that’s so central to avoiding misunderstanding and misperceptions among international actors and maintaining international peace. Players will be tempted to stick to official stances, substitute rhetoric for real conversation and avoid straying from formal positions. Some of this will be the result of conscious choice; some will be the consequence of subliminal caution. Much will be in response to official directives from alarmed governments. Ironically, the attempt to celebrate transparency in one sphere may lead to a premium on opacity in another.

For several countries, the impact of WikiLeaks will influence not only diplomatic conduct but domestic politics. Conversations between Indian officials and US leaders or diplomats, reported in these cables, could well revive suspicions of US meddling in India. Depending on reported conversations or subjective assessments by US diplomats, some who figure in the cables will be branded either as US stooges or champions of the national interest.

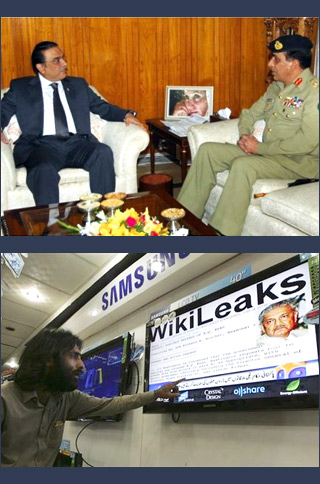

The US Embassy’s assessment that India was unlikely to carry out punitive military operations against Pakistan even if there was another Mumbai-type of terrorist attack because of a fear of nuclear escalation, has already been taken, in some quarters, as evidence of US contempt of Indian capabilities and doubts about India’s will to fight. The opposition will find it tempting to attack those in power associated with the policy of closer relations with the US. In Pakistan, one wonders about General Ashfaq Kayani’s musings on a possible replacement for President Asif Ali Zardari and the effect on Zardari’s already beleaguered position. And since it’s known that there are divisions in the Chinese leadership on how to deal with North Korea, there could be domestic political consequences for a Chinese official airing the possibility of a united Korea under Seoul with Chinese acquiescence.

Much of the material released so far does not break new ground. In fact, the cables mostly confirm what’s already widely known about US perspectives on international issues and assessments of different world leaders. These may be expressed in more colorful language and in a more forthright manner, but at the end of the day, few major surprises are sprung, certainly not to assiduous newspaper readers or those in the diplomatic business.

There are important exceptions. It did come as a surprise that US diplomats are asked to gather incredibly detailed personal data, credit card numbers and DNA included, on foreign counterparts, a job that would be more appropriate to intelligence operatives. This disclosure will certainly complicate the work of US diplomats. I expect Indian and Chinese ambassadors in New York paying in cash rather than with credit cards the next time they take US counterparts to dinner!

The revelation that the Chinese may be willing to accept a united Korea under Seoul, if true, is newsworthy. And of concern to India specifically, is an obscure remark attributed to a senior British official, who “expressed support for the development of a ‘cold war’–like relationship between India and Pakistan that would ‘introduce a degree of certainty’ between the two countries in their dealings.” It’s not at all clear in what form this “support “ would likely be extended, particularly against the background of numerous expressions of concern over the security of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons, its relentless pursuit of a larger nuclear arsenal and the acquisition of tactical nuclear weapons which have dramatically lowered the threshold of nuclear-weapon exchange. What, one wonders, is the “degree of certainty” to which the official alludes.

The overall impact of WikiLeaks will increase constraint and decrease trust.

Firstly, both information- and assessment-sharing among nations will likely become constrained and restricted precisely at a time when these are required more than ever before to prevent misunderstanding and misperceptions in a rapidly changing international landscape. US diplomacy alone won’t suffer, the constraint will disrupt international diplomacy in general.

Secondly, while the disclosures do not spring major surprises, they will influence US domestic and regional politics of several countries and affect the political fortunes of current political leaders and actors – from Silvio Berlusconi to Zardari.

Thirdly, the WikiLeaks effect will last longer if there’s a series of such disclosures in the coming weeks and months. The threatened release of internal documents of banks could have serious repercussions for the market. The spread of the internet and the ease with which confidential information in many countries is being regularly accessed and disseminated in our digital age may point to a more enduring and broader challenge than the current disclosures.

Governments across the world have shown an inability to come to terms with 24/7 news coverage and instant media. Without a well thought out strategy to manage communications in general, hiding less from their citizens, governments will find it virtually impossible to keep pace with, let alone manage, new social media such as Twitter, Facebook and the blogosphere.

Rather than hunker down in the face of the WikiLeaks, damaging as they may appear to be, it would be worthwhile for governments to learn to ride the communications wave rather than be swept aside by it. It’s inevitable that there will be severe limitations put in place for the handling of confidential information, but these by themselves are unlikely to eliminate the risk of future WikiLeaks-type disclosures.

There must be, in parallel, a strategy that develops capacity within governments, to understand and influence the impact that digital media, social network sites, electronic media and the internet in general are having on the creation of public and political opinion, both at home and abroad. This will enable them to deal with future WikiLeaks as part of managing the overall challenge of a much more interconnected and instantly perceived real-time world.

Shyam Saran is the former foreign secretary of India.