Will Another Cold War Follow Trade War?

Will Another Cold War Follow Trade War?

This essay is based on a paper prepared for the 20th Annual China Development Forum, March 22 to 25, 2019, in Beijing.

BEIJING: The United States and China will likely reach a trade deal, but this will hardly be the breakthrough that ends a deep-rooted conflict. A likely deal will focus primarily on multiyear narrowing of America’s outsized bilateral merchandise trade deficit with China, which hit an astonishing $419 billion in 2018, nearly half the total US trade gap. But there is no bilateral fix for America’s trade deficit with 102 countries last year. The multilateral imbalance stems from a profound shortfall of US domestic saving, only worsening in the years ahead due to chronic and widening federal budget deficits.

Instead of popping champagne when such a deal is reached, government officials and investors should think ahead to unresolved structural issues that remain – over technology, intellectual property rights, state-sponsored industrial policy, and forced technology transfer through joint venture arrangements – all pointing to a protracted conflict long after the ink dries from another glitzy signing ceremony.

Consistent with the ominous warnings of Vice President Mike Pence and former US Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, such an outcome points to the distinct possibility of an economic cold war, with the United States and China locked in a protracted clash over the competitive strategies of two very different economic models. A year ago, the so-called Section 301 complaint of the US Trade Representative made the case for China as an existential threat to America’s economic future. While my analysis suggests that the evidence behind these allegations is weak, the United States seems determined to push ahead on these fronts – many key to China’s own longer-term economic strategy.

America does not have a monopoly on existential fears as this relationship veers off course. China has deep-rooted concerns that that the United States is fixated on a “China containment” strategy – doing everything in its power to throw up obstacles to the next phase of Chinese development. While Trump’s tariffs underscore these concerns, they follow on the heels of the Obama administration’s “Asia pivot” and Trans-Pacific Partnership ambitions – with the latter excluding China from its original 12-nation framework.

Inasmuch as I do not expect China to capitulate on its core economic strategy, there is a strong likelihood of a protracted struggle between two systems – call it Cold War 2.0. This, of course, would contrast with Cold War 1.0, more of a military struggle between the United States and the former Soviet Union.

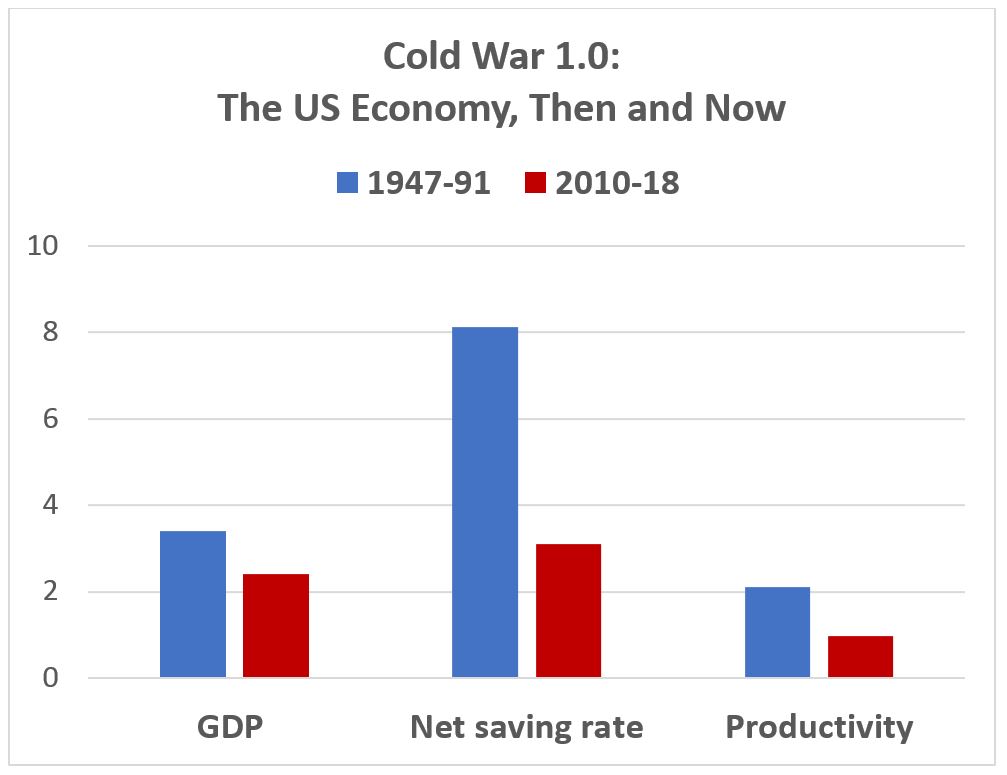

Significantly, for the United States, its economy is in much weaker shape to wage a cold war today than was the case during Cold War 1.0 from 1947 to 1991. During that earlier period, real US GDP growth averaged 3.5 percent per year. By contrast, since 2010, real US growth has slipped to 2.3 percent. Similarly, during the first cold war, productivity growth averaged 2.2 percent per annum, while over the past nine years the pace has slowed to 1.1 percent. And equally, if not more significant, America’s domestic saving position is woefully deficient – a 2.5 percent net national saving rate since 2010 versus an 8.8 percent average during Cold War 1.0.

Such a profound shortfall of saving raises especially serious questions about America’s wherewithal to fund the investments in physical or human capital required for competitive revival. The United States today lacks the economic strength that it had in taking on the former Soviet Union in the first four decades of the post-World War II era.

Contrasting global perspectives of the United States and China were evident from the beginning of the Trump administration. Donald Trump said in his January 2017 inaugural address, “Protection will lead to great prosperity and strength.” Three days earlier on January 17, Xi Jinping gave the keynote address at the World Economic Forum in Davos, suggesting that China “should adapt to and guide economic globalization.”

Both nations have moved to act forcefully on those statements, especially evident with Trump’s resistance to multilateralism – withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Paris Agreement on Climate Change and threatening to do the same with NATO and the World Trade Organization. Meanwhile, Xi has endorsed multilateralism through China-centric efforts such as the Belt and Road Initiative, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, each launched before Trump’s presidency.

Trump mistakenly believes that tariffs will “make America great again” by restoring US manufacturing jobs; however, with the manufacturing share of US employment down from 40 percent in the aftermath of World War II to just 8.5 percent today – in large part due to technological and productivity enhancements – that is all but impossible to achieve. By contrast, Xi’s multilateralism draws on the efficiency enhancements of trade liberalization, global value chains and, hopefully, renewed commitment to the rules-based governance of globalization – principles that place greater emphasis on the collective growth opportunities for the world economy.

The last thing the global economy needs is a breakdown of the post–World War II world order, with integration and trade liberalization giving way to fragmentation and currency and trade wars. Collectively, only the United States and China are in a position to neutralize this risk. Yet they can do so only if both operate from a position of strength.

In the codependent US-China relationship, strength and healing can ultimately only come from within. If both the United States and China address their own economic issues and imbalances, they can better resolve the issues that have come between them. For China, that means continuing to focus on rebalancing and structural change by putting its vast reservoir of surplus savings to work in tackling domestic challenges. For the United States, that means addressing its chronic shortfall of domestic saving and putting new increments of saving to work in rebuilding the infrastructure, manufacturing capacity and human capital required for competitive revival.

Contrary to the view of the Trump administration, trade wars have no winners – especially between two codependent economies that rely so heavily on each other as do the United States and China. Trump’s argument that the United States has the upper hand in a trade war because China is already hurting could be a serious miscalculation. Yes, the Chinese economy is weakening and likely to slow further in the months ahead. But in light of recent policy stimulus actions, both monetary and fiscal, that weakening could run its course by mid-year. On the other hand, the sharp plunge in the US stock market in December 2018, in conjunction with a significant weakening in global trade, point to a test of US economic resilience in the months ahead.

Notwithstanding a likely superficial deal between the United States and China, it is hard to be optimistic that a meaningful breakthrough is at hand. Nothing short of bold, courageous and strategic vision by leaders of both nations is required to restore trust and rebuild the relationship.

Only by strengthening from within can the world’s two largest economies transform their relationship from a destructive codependency into a constructive interdependency. Such reshaping of the US-China economic relationship would then once again reinforce their respective growth journeys rather than create frictions that pose serious impediments to their shared future. Unfortunately, the odds of a weak deal far outweigh the possibilities of a more substantial and lasting agreement that diffuses the existential threats that both nations fear the most. A protracted conflict in the form of Cold War 2.0 threatens not just the United States and China but the world economy.

Stephen Roach, a faculty member at Yale University and former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, is author of Unbalanced: The Codependency of America and China (Yale University Press: 2014). This essay is based on a paper prepared for the 20th Annual China Development Forum, March 22 to 25, 2019, in Beijing.