Will Japan Emerge from its Shell? – Part I

Will Japan Emerge from its Shell? – Part I

NEW YORK: At the recent Copenhagen climate summit, Japanese negotiators were virtually invisible, at least as reported in the media. Japan is often described as playing a much smaller role in global affairs than one might expect of the world’s second largest economy. Japan’s shyness in taking a more forceful role commensurate with its economic clout could ultimately reinforce its declining economic trend.

Why should one expect Japan to play a more prominent role in global affairs? The core issue is global public goods such as maintenance of peace and security or leadership in the effort to confront other global challenges (climate change, depletion of ocean fish stocks, the ozone hole, etc.). There are no hard and fast rules obligating governments around the world to contribute to these public goods, and over the past 60 years the United States has shouldered a large part of the burden. Americans seem to believe that doing so is a moral obligation of affluent societies – those that have the economic resources to make a real contribution. Since enhancing these global goods can be expected to contribute to a more equitable, peaceful and stable world it should be in the self-interest of successful globalizing economies like Japan to bring useful ideas to the international negotiating table. Therefore, ever since Japan joined the ranks of the leading affluent nations in the 1970s, it has been under pressure from the US government and others to “do more” through increased foreign aid, participation in UN peacekeeping missions, engagement in multinational military operations (even if only in a non-combat role), or greater leadership in organizations like the WTO to help the world become more open to trade and investment. Japan has indeed “done more,” but its efforts still seem smaller than many around the world expected. Why?

The roots of Japan’s hesitant role go back to the mid 20th century. First, Japan’s military aggression in the Second World War led to vast death and destruction for other Asians and the Japanese themselves, leading to a strong postwar sense of guilt or shame. The logical path for the nation, therefore, was to simply stay at home, contributing to world peace and stability by not being in a position that might potentially cause further trouble. Over the past 20 years, attitudes have shifted, but deep skepticism concerning the efficacy of Japanese military power remains among the public.

Second, Japan did not develop a strong agenda to press upon the rest of the world. Arguably, the United States took on the role of providing global public goods because it has had an agenda to push – anti-Communism, democracy, and a belief in free markets. In the late 1980s, the government made an attempt to sell the Japanese economic model of development as an alternative to the set of free market policies being pushed at the time by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, labeled the “Washington Consensus,” but this effort faded when a subsequent decade of economic stagnation took the luster off the model. Nothing has taken its place.

Third, following the end of the Second World War, Japan pursued a very protectionist trade and investment policy. Those barriers have fallen substantially, but the legacy of the past has kept the government from playing a leadership role in the WTO.

Finally, Japan is one of a relatively small number of nation states that has a rather homogenous society. There are minorities in Japan, but the numbers are relatively small. Even including Koreans born in Japan (without citizenship), the foreign population in Japan is only 1.6 percent of the total, for example. This ratio has doubled over the past two decades, but remains far below the level of the United States (12 percent) or European nations (8 percent in France, or 10 percent in the United Kingdom). Not having much daily contact with people from other cultures at home leaves the Japanese less experienced and uncomfortable in international interaction.

Offsetting these obstacles to a more prominent engagement in global public goods have been two important developments. First, since the mid 1980s Japanese firms have invested actively abroad. Many of the Japanese managers assigned to run these overseas operations have taken their families with them. From 1985 to 2006, the number of Japanese living abroad (for three months or more) other than permanent expatriates tripled (to 635,000). Second, increasing numbers of Japanese students have studied abroad. In the United States (where the bulk of Japanese students abroad are located) the number of students enrolled expanded from only 10,290 in 1985/86 to a peak of 47,073 in 1997/98. Unfortunately, by 2008/09 this number had fallen 38 percent to 29,265 (while the total number of international students in the United States expanded by 40 percent). Nonetheless, the larger number of Japanese with experience living abroad – managers, their families, and students – should be creating a larger cadre of individuals capable of engaging more easily in international settings.

Given this legacy of obstacles and mitigating trends, can or should Japan play a more prominent role in the world going forward? The prognosis is not good. It seems likely that the Japanese will quietly watch the world go by as their own population falls, the economy stagnates, and society becomes absorbed in coping with the political and fiscal stresses resulting as the population continues to age. But with greater capacity to interact with the rest of the world are there some areas in which Japan might take a more active role? On security issues, Japan probably will not be more active. The inhibitions stretching back to the Second World War remain strong, and two decades of American pressure have failed to move Japan very far along toward the international projection of military force. Frankly, if Japanese society is uncomfortable with this role, one should respect their reticence. But what about other areas?

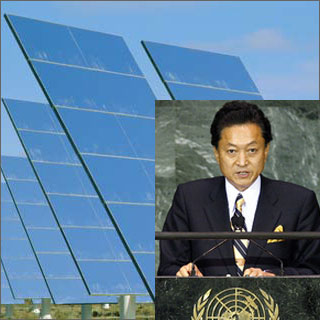

One possible opportunity for greater activism should be climate change policy, because the Japanese have something to bring to the negotiating table. Since the spike in oil prices in 1973, the Japanese government has pursued a vigorous program of developing alternative energy sources (principally nuclear) and greatly improving energy conservation. Japanese firms are among the global leaders in several alternative energy production technologies (including solar cells) and energy-saving technologies. Success in reducing domestic energy consumption per unit of economic output and increasing the use of non-fossil fuel energy sources implies that the Japanese should have something to say in international negotiations. At Copenhagen, at least the Japanese offered their own strong unilateral commitment on cutting emissions, and offered a sizable contribution on aid to poor countries once the wrangling over aid was settled.

If the world really wants Japan to do more, then cajoling the government to be more engaged in areas such as the debate on how to accomplish carbon emissions goals might be fruitful. Another might be to press Japan to be more active with foreign aid in Afghanistan and other troubled countries as a substitute for military involvement. But ultimately the Japanese must decide for themselves whether they want to come farther out from their shell. A society so insular that it cannot embrace a substantial inflow of immigrants to offset its declining population, however, might not step up to the international role that the world expects.

Edward J. Lincoln is the director of the Center for Japan-US Business and Economic Studies and Professor of Economics at New York University Stern School of Business.