Winners and Losers After Arab Spring

Winners and Losers After Arab Spring

TRIPOLI: Transitions in Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia have yet to extend opportunities for political participation and good governance. Frustration with the slow, halting progress in bringing representative democracy there might lead foreigners to recommend a procrustean solution, but what the countries need is a differentiated approach.

The ouster of President Mohamed Morsi and the violent repression of his supporters in Egypt highlight the fragility of representative institutions vis-à-vis the ideological divide and conflicting interests. Tunisia has seen its share of economic and political struggles. While its transition process has been the most successful to date, the hard task of ratifying the constitution and holding elections lies ahead. Libya faces the challenge of armed militias and building the capacity and legitimacy of state institutions. Behind headlines focusing on national struggles lurk differences in who is empowered, who is sidelined, in the transition processes. The challenges and possibilities for international efforts aimed at strengthening democratic politics are not uniform across the countries.

Findings from the Transitional Governance Project, a series of post-election surveys conducted in Tunisia1 and Egypt2 in fall 2012, and Libya3 in spring 2013, reveal three lessons:

-

the need to expand the focus on women and youth to greater attention to disenfranchised rural and less-educated citizens;

-

the need to distinguish between sidelined groups whose preference across critical issues match their more engaged counterparts and sidelined groups whose viewpoints are not represented;

-

the need to understand the significant differences across countries among the groups that are enfranchised or sidelined in the transition process. A one-size-fits-all approach to the transition processes – and particularly to development assistance aimed at fostering democratization – is unlikely to be effective.

Governance programs today place heavy emphasis on women and youth. Three assumptions underpin this approach: first, that youth have been under-represented, and could mobilize and undermine stability; second, that women are sidelined and under-represented in the public sphere; and third, that women and youth have needs and preferences not otherwise met.

But these assumptions are only partly true. A large number of youth are mobilized, but so too are middle and older groups. In both Egypt and Tunisia, youths participate to the same extent in political parties and to a lesser extent in elections. In Libya, youth participated more in elections; 76 percent voted, compared to 67 percent of those aged 30 and older.

Women are generally excluded before and after transitions. In both Egypt as well as Tunisia, women are less engaged in political parties and participate less in elections. The gap between men and women voting in Egypt has decreased following the revolution, but the opposite holds true in Tunisia, where women and men voted with near-equal frequency before the transition, but women lagged behind in the October 2011 elections that followed. Libya has the largest gender gap for voting of all three countries.

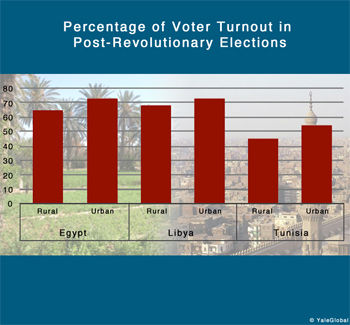

Yet other segments of society need attention. Rural citizens are disenfranchised through transitions. In both Egypt and Tunisia, the rural population participated more than urban counterparts in elections before the revolution. In Egypt, 41 percent of rural citizens voted, compared to 29 percent of the urban population. In Tunisia, 40 percent of rural citizens voted, compared to 36 percent of the urban population. Following the revolution, urban citizens have become more mobilized and now more participate in elections (Figure 1).

The most disenfranchised group in Egypt, Tunisia and Libya is the poorly educated. The polls suggested that they were unlikely to protest before and during the revolution, are not engaged in political parties, and actually became less likely to vote after the revolution.

The concern is not simply whether groups are absent from the political process, but whether their preferences over policies are as well. Unequal participation can be exacerbated by a preference gap. The survey findings suggest that the greatest preference gaps are not between the groups that receive attention: men and women, or young and old. Rather, the most significant gaps are between rural and urban dwellers, and the more- and less-educated.

Young and old differ along some public policy issues, but not to a great extent or in a consistent manner across countries or issues. For instance, young and old hold similar views on whether religious leaders should have a strong role in government, although differ on support for Islamists; in Egypt, middle-aged voters are slightly more likely to support Islamist parties, while in Tunisia and Libya, younger voters were more likely to do so. On economic issues, Egyptians and Tunisians generally favor a strong role of state in the economy, while Libyans tend to favor a capitalist system. Across the board, however, youth are more likely to prefer less state intervention in the economy. On questions of gender, young and old Egyptians hold similar attitudes regarding discrimination in employment, while in Tunisia and Libya, youth are more likely to support measures to increase women’s political representation than older cohorts.

Preferences of men and women are also not distinct. In Tunisia, women and men are equally likely to vote for Islamist parties; in Egypt women are more likely to do so; and in Libya, there’s no difference. Men and women also hold similar attitudes regarding the role of the state in the economy and the relationship between religion and the state. Finally, with regard to gender issues, Egyptian and Tunisian women are only slightly less conservative than men, while in Libya, they are much less so.

In contrast, rural and less educated populations hold contrasting values. They are more likely than their educated, urban counterparts to consider the economy a priority and equate democracy with economic welfare and equality. They are more likely, too, to prefer a relationship between religion and the state and to support Islamist parties, and to seek a strong role of the state in the economy. With regard to gender issues, they generally hold conservative views on women’s participation.

Taken together, the evidence calls for rethinking government assistance:

-

Expand the focus from women and youth to include the less educated and rural classes;

-

Distinguish between the preference gap and participation gap. Expanding inclusive participation is a benefit in itself, but only when the participation gap is matched by a preference gap can new voices contribute to policy outcomes;

-

Recognize that these gaps vary across Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, and elsewhere.

Only by taking a close, case-by-case look at the challenges facing transitional societies can appropriate policies be shaped and development assistance effectively applied. The same holds true for understanding the dynamics of transitions – including developing conditions in Egypt, where differences in religious orientation between supporters and opponents of the ousted president also mask differences among urban and rural and more and less educated segments of society.

Notes on Surveys:

(1) The Tunisian Post-Election Survey (TPES) was conducted by Benstead, Lust, and Malouche, with support from the National Science Foundation, Portland State University, Princeton University and Yale University.

(2) The Egyptian Post-Election Survey (EPES) was conducted by the Al Ahram Centre for Political and Strategic Studies (ACPSS) in collaboration with Lust, Soltan, and JMW Consulting with support from the Danish Egyptian Dialogue Institute.

(3) The Libyan Post-Election Survey (LPES) was conducted in collaboration with the National Democratic Institute, JMW Consulting, Benstead, Lust, and Diwan Market Research. The survey was funded by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.