WMD Risks in Civil War: What Syria Can Teach

WMD Risks in Civil War: What Syria Can Teach

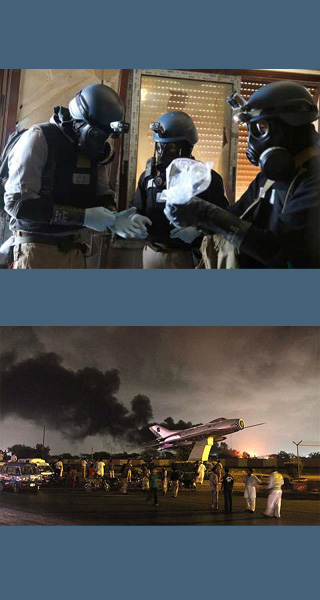

LOS ANGELES: The success of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons in eliminating Syria’s chemical production sites, coupled with the commencement of the removal of chemical agents out of the country by sea, mark important milestones in ridding a deadly arsenal. Yet a look at events that preceded the Kerry-Lavrov disarmament deal exposes a gaping hole in the international community’s capacity to contain weapons of mass destruction in serious civil strife generally. But for the September 2013 eleventh-hour "Hail Mary pass" – the desperate lob at the end of an American football game to retrieve victory from jaws of defeat – Washington and its allies didn’t have a clue how to stop Syria’s chemical use or movement, the litmus test of President Barack Obama’s red line.

The head-scratching raises a more fundamental question: What will the US and others do when the next civil war poses even more daunting WMD perils, namely nuclear weapons and reactors? Think Pakistan and North Korea, and the possibilities become plausible. Both nations face the specter of serious domestic turmoil in the years to come.

Let’s start with Pakistan, the most concerning case. A nation wracked by decade-long civil strife that has taken the lives of more than 50,000 and included sophisticated attacks on heavily guarded military installations, Pakistan possesses more than 100 nuclear weapons, materials for many more as well as a large production complex that includes reactors terrorists could sabotage to release radioactive contents.

In North Korea we find a country with 10 or so nuclear devices latched to a dynasty that faces chronic economic dysfunction, a famished population, the globe’s largest gulag and periodic purges of senior officials, revealed for all the world to see in the remarkable recent public arrest and execution of Jang Song Thaek, the country’s number two. Despite the Kim family’s staying power, Pyongyang watchers suspect that continuing economic and political dysfunction will translate into state collapse someday, risking diversion of nuclear material out of the country and, possibly, nuclear use should the dying regime decide to take neighboring nations down with it, intentionally or due to failure of command and control.

So is Washington prepared? Efforts to prevent chemical weapons use in Syria provided a test, and the results give little confidence.

In February 2012, the Pentagon estimated it would take some 75,000 ground troops to find and lock down Syria’s arsenal. With the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan still fresh in many minds, American decision makers were in no hurry to give the green light. Rather, Washington adopted a policy of soft coercive diplomacy. In August 2012, the president announced his “red line.” Joint military exercises in Jordan in May 2012 gave spine to the threat. But the Syrian government evidently was unimpressed, first moving and then using chemical weapons possibly as early as December 2012.

By January 2013, Washington’s red-line overseers got cold feet. Responding to reporters, Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta declared Syria’s “hostile situation” would not allow the sending of US ground troops to handle the chemical issue. At the same news conference, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Martin Demsey added, “the act of preventing the use of chemical weapons would be almost unachievable.” The absence of “clarity of intelligence” was held out as one reason.

As spring came, Dempsey attempted reassurance. “We have the planning done,” he told the Senate Armed Services Committee. However, pressed by legislators, he could not avoid the intelligence hole. The implications became clear when Washington placed rocket-launching naval vessels in the eastern Mediterranean in early September in response to the August 21, 2013, chemical attack that killed 1,400 Syrians in the Ghouta suburb of Damascus. The intelligence hole then became a political albatross. The administration failed to make a convincing case that a limited military strike would eliminate the chemical arsenal and apprehension emerged that such an attack would be the first step to sucking the United States into yet another war.

Looking forward, does the intelligence picture change when it comes to more concerning nuclear risks elsewhere? Not in North Korea. Yes, Washington knows the location of the Yonbyong reactor and enrichment plants. South Korea claims to have intelligence on many more nuclear-related installations. But much remains a black hole. Knowledge about Pakistan may be greater, but large gaps that long existed may have only grown as Islamabad accelerated nuclear concealment after the Osama bin Laden raid.

Pakistan and North Korea, of course, are not America’s problem alone. India and South Korea would face the most acute security challenge if the respective hostile neighbors lost control of nukes. But neither country has Washington’s broad capability to respond or lead a response – and what response remains the question.

Consider the spectrum: At one end, the world sits tight and does nothing, which might seem odd but history shows “nothing” often works in civil strife. During the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Great Cultural Revolution, the 1961 Generals Revolt in Algeria and the Yugoslav civil war, nuclear weapons or materials were at risk, but no consequence followed. Government command and control held, and leaders did not turn the weapons on their people. But one cannot be too sanguine about the past. Had tipping points gone another direction the results would have broken nuclear safeguards.

What if nuclear dikes begin to fail? Does an Iraq 2003 redux – invasion and occupation – make sense or does it bring another American quagmire? Would quagmire be worth the risk next time if the result really did eliminate vulnerable nuclear assets? Would limited force – airstrikes or introduction of special forces – make more sense or would it provide a false sense of security since only a serious number of boots on the ground can ferret out concealed sites?

Alternatively, does less kinetic action mark a better choice? Possibilities include a cordon sanitaire along borders of troubled nations to block migration of nuclear assets, providing intelligence and military equipment, for example, to Islamabad to enhance nuclear security – assuming the government remains intact – and appealing to the professionalism of North Korean and Pakistani nuclear custodians to protect their nations if the states collapse or issue entreaties to rebels to guard nuclear sites or enhance homeland security or live with measures already in place that have protected countries since 9/11. Some options are simple stopgaps, but stopgaps can buy time until stability returns or lend a false sense of security.

The fog of events can make decision making difficult, but planning must be in place to anticipate. Given the stakes, Washington’s planning should reflect not simply the confidential conclusions of the national security bureaucracy but the vetting and input of Congress, nongovernmental experts and public debate. It’s not sufficient that the US president, even under the authority of the War Powers Resolution or other claim, be the exclusive decider. And because civil conflict can erupt without warning, as Syria and other countries in the region demonstrated repeatedly in recent years, thinking the unthinkable deserves broad attention sooner rather than later. Ducking the issue, hoping that another last-minute Syria-like solution will save the day, is like the Hail Mary pass, too much the long shot that is best avoided by having a better game plan.

Bennett Ramberg, PhD, JD, served in the Bureau of Politico-Military Affairs in the US Department of State during the George H.W. Bush administration. He is the author of “Nuclear Power Plants as Weapons for the Enemy,” University of California Press, and can be reached at bennettramberg@aol.com.